Page content

Duke of Gloucester Street

- Principal street in the town

- Began as narrow trace

- FDR called it “most historic avenue in all America”

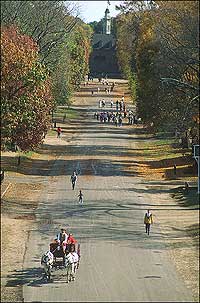

When Virginia's General Assembly created Williamsburg in 1699, it ordered that its main street “in honor of his Highness William Duke of Gloucester shall for ever hereafter be called and knowne by the Name of Duke of Gloucester Street.” When President Franklin Roosevelt visited 235 years later to dedicate Duke of Gloucester Street's reconstruction, he said it “rightly can be called the most historic avenue in all America.”

George and Martha Washington and Thomas and Martha Jefferson are among the men and women who have walked it. Bill and Hillary Clinton, Ronald Reagan, Lyndon Johnson, Dwight David Eisenhower, Harry Truman, and Winston Churchill are among those whose feet have trod in the steps of the likes of Peyton Randolph, George Wythe, St. George Tucker, Patrick Henry, and James Madison.

Humble beginnings

The august avenue known as Duke of Gloucester Street began as a narrow Indian trace that rose to the dignity of a horse path in the 17th century. In those days the community that would become Williamsburg was called Middle Plantation. Through the little village, the horse path followed the crest of the meandering ridge that separates the watersheds of the James and York Rivers. When the Virginia legislators grandly gave it the name of the heir to the English throne, Duke of Gloucester Street rolled through a series of swampy ravines and at one point was obstructed by houses.On April 27, 1704, Francis Nicholson, Virginia's governor and Williamsburg's designer, asked the House of Burgesses to buy four old homes and an oven that stood in the way and have them demolished. On May 5, the burgesses voted to order Henry Cary and a work crew to tear the structures down, gave owner John Page £3, and let him have the bricks from the rubble.

Street’s current path mandated 300 years ago

Often referred to as the “main street” or the “great street” in the 18th century, Duke of Gloucester Street was to be 99 feet wide and run nearly a mile straight from the College of William and Mary on the west to the Capitol on the east. The General Assembly decreed in 1705 that it “shall not hereafter be altered either in ye Course or Dimensions thereof.”

Early building codes

The burgesses required houses on the half-acre lots along its length to be at least 20 feet wide and 30 feet long, with roofs of 10-foot pitch. Many of the lots were taken up, but initially building lagged despite inducements. There was little economic incentive to town building, and Williamsburg still was not far removed from the wilds.

Colonial “potholes”

Carriages and horses making their way downtown — the Capitol end of the city — sank from view on Duke of Gloucester Street and rose again as they climbed in and out of gullies and ravines. There was one by Bruton Parish Church, another near the Capitol, and others, traces of which can still be seen. Citizens complained of the “Irregularities of the principal street.” On November 28, 1720, the burgesses resolved “That the Sum of one Hundred and fifty Pounds be given towards making Bridges and Causeways in the main street.”

Little could be done, however, about the sandy clay soil. In dry weather, traffic churned up clouds of choking dust; in wet weather, the street became a muddy slough. Well into the 20th century the town joke was that Duke of Gloucester Street was 99 feet wide and two feet deep in the rain. A William & Mary professor once set his class to calculating the volume of mud in cubic yards.

Yet, in any weather Duke of Gloucester remained the city's principal axis. Governors in gilded carriages rode down it to the Capitol and, in at least once instance, in a hearse to the grave. Ordinary traffic — horse chairs, oxcarts, wagons, and stages — vied for rights of way with wandering chickens, stray sheep, and visiting frontiersmen. There were mobs — like the one that gathered on the night in 1775 when the theft of gunpowder from the magazine was discovered — and parades to celebrate occasions like the defeat of Burgoyne in 1777.

Street falls to neglect

But like so much else of Williamsburg, the avenue slipped into neglect after the government moved to Richmond in 1780. Journalist Benson Lossing visited Williamsburg in 1848 and described Duke of Gloucester Street as a “broad avenue, pleasantly shaded, and almost as quiet as a rural lane.”

Wounded on wagons, dignitaries on trains

The peace was disturbed by the War Between the States when wagons carried wounded from both sides in the Battle of Williamsburg to makeshift hospitals along its route. In 1881, it rattled to the construction of a temporary railroad track down the street to ferry visitors to the centennial celebration of the Siege of Yorktown, and to Newport News.

Still, cattle and other livestock roamed the idle avenue and much of the town, into the 19th century. The eccentric Peyton Randolph Nelson sometimes turned his herd of western ponies loose on Duke of Gloucester Street to forage where they might.

Lazy street in 19th century

Of those times Mayor George P. Coleman wrote, “Williamsburg on a summer day — the straggling street, ankle deep in dust, grateful only to the chickens, ruffling their feathers in perfect safety from any traffic danger; the cows taking refuge from the heat of the sun, under the elms along the sidewalk; Our city fathers, assembled in friendly leisure, following the shade of the old Court House around the clock, sipping cool drinks, and discussing the glories of the past. Almost always our past . . . the past alone held for them the brightness which tempted their thoughts to linger happily.”

At the Southwest corner of Market Square stood the firehouse with its tower and City Hall, which was housed in the building with balcony. On the corner stands a service station.

20th-century “progress“ completely destroys character

But Duke of Gloucester Street's character, and the character of the town itself, changed with the construction of a World War I munitions facilities nearby. A postwar photograph, taken from the College yard in 1926, shows a thoroughfare as ugly as it is wide. Two slashes of concrete carry U. S. 60 toward Newport News on either side of a row of utility poles that ran down the center of an unkempt median. Cars of the Model A era are parked at the curbs as far as the lens can see, and electricity and telephone wires span the sky above them. Concrete sidewalks confine the lawns of historic old homes and beat paths to gas stations and dry cleaning stores.

Among Colonial Williamsburg's early restoration goals were the removal of the poles and the median, the rerouting of the highway, and the relocation of the utility wires underground. By 1933, much of the plan had been accomplished, but daytime automobile traffic on the thoroughfare was not halted entirely until 1969.

Restoration returns street to simple grandeur

To walk down Duke of Gloucester Street today is to step into the 18th century. Between the Wren Building and the Capitol, in a stroll of less than a mile, among the sights the visitor may enjoy are the Weaver's Shop; Bruton Parish Church, Palace Green, the John Greenhow Store, the James Geddy House, the Mary Dickinson Store, the Shoemaker's Shop, Market Square, the Courthouse, the Magazine and Guardhouse, Chowning's Tavern, the Ludwell-Paradise House, the Printing Office, the Prentis Store, the Post Office and Bookbindery, M. Dubois Grocer's Store, the Mary Stith Shop, Tarpley's Store, Wetherburn's Tavern, the Milliner, the Silversmith, the Raleigh Tavern with its Bake Shop, the King's Arms Tavern, the Pasteur & Galt Apothecary Shop, and the Secretary's Office.

For further reading:

- Capitol

- Bruton Parish Church

- Court House

- Magazine

- Wren Building

- James Geddy House

- Market Square

- Guardhouse

- Ludwell-Paradise House

- Printing Office

- Mary Stith Shop

- Wetherburn's Tavern

- Milliner

- Raleigh Tavern

- Pasteur & Galt Apothecary Shop

- The Duke of Gloucester Street Special

- College of William & Mary website