Page content

The Pineapple in Colonial Williamsburg

Decorating with pineapples

No one knows for certain exactly how the pineapple became an essential element in the Christmas decorations of Colonial Williamsburg, but a look at the history of the sweet fruit provides an educated guess and a likely answer.

Native South American plant

The pineapple is native to South America and was likely imported to the Caribbean by native tribes, who brought the sweet fruit with them and transplanted it on several islands. Spanish explorers record finding the fruit and marveling at its sweetness in the 16th century. The Dutch took the plant to Surinam, where they cultivated it and eventually took it to Holland to try to grow it in greenhouses. In the 18th century, the British attempted to grow the tropical plant in specially built hothouses. Because the exterior of the fruit resembled the pine cone, and the sweet fruit was similar to the texture and taste of an apple, the name was changed from its original “anana” to pineapple.

Although we usually associate the pineapple with Hawaii, it is not native to those islands either, having been transplanted there from Jamaica by the British in 1886, a full 200 years after the fruit had been cultivated and consumed in Europe.

Christian and imperial significance

Each pineapple plant gives its own life to produce a single fruit, and since 1681, the pineapple has been recognized as a Christian symbol. Around this time, Christopher Wren began using pineapple finials on churches.

The pine cone has a long-held imperial significance. The Romans placed pine cones on their buildings and monuments to symbolize confidence in the administrative, judicial, and defensive power of the state, possibly following the practice of the Babylonians. Thus the use of pineapples on Wren's great public buildings may mimic the pine cones on Roman buildings, with the added luster of English colonial power. Pine cones are also a mechanism for displaying and spreading seeds, and thus bring to mind fertility, a valuable characteristic for any society, and certainly for an empire.

Shipments from Barbados and Bermuda to London

As the pineapple was making its way into Anglo-American culture, Captain Richard Ligon boarded the ship Achillis bound for the West Indies from London. In 1657, he published an account of his travels, including a history of the Island of Barbados. He devoted three pages to the pineapple. Diaries from the period mention gifts of pineapples presented to the king. And ships' manifests from the late 17th century contain lists of pineapples making their way from Barbados and Bermuda to England, often rotten upon arrival.

The sweetness and unusual appearance of the pineapple and its association with fertility and agriculture made it a sought-after delicacy in colonial America. When it was served to guests, they were naturally flattered at the honor, and thus may have evolved the idea that the pineapple was considered a sign of the highest form of hospitality.

Subject of artists

The fruit became the subject of artists, and in 1661, it became an integral part of the coat of arms for the colony of Jamaica – a silver shield with a red cross and five golden pineapples adorning it. An Arawak woman supports the arms on the left, and she is holding a basket of fruit, including the pineapple.

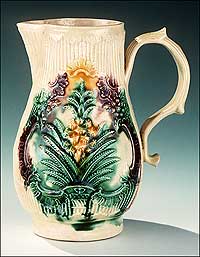

The fruit was again and again imprinted, impressed, painted onto or sculpted into all manner of objects, buildings, wallpaper, fabric, dishes, and mementoes.

Foundation collections include numerous items with pineapple motif

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's collections include a glazed earthen jelly mold with an impression of a pineapple on top, made around 1780, and a multi-tiered silver dessert tray with a large cast pineapple under a pagoda roof made in 1763. A tall clock made in Pulaski County, Va., in 1809 includes an inlaid pineapple 10 inches high made of mahogany, cherry, and pine. In the Louvre in Paris, a collection of 18th-century snuff boxes made in Dresden includes one with a top with a green and yellow pineapple in a field of other tropical fruits.

In Williamsburg, archaeologists found large shards of Wedgwood pineapple ware similar to the "green and gold glaze" tea, cream, and sugar set now on display in the DeWitt Wallace Museum of Decorative Arts.

Pineapple ware was popular for a short time in England in the 1760s, but by 1770 Josiah Wedgwood expressed relief that his overstocks had been sent to the colonies. But in Virginia, a century of devotion to the pineapple would not be eclipsed until the decorative arts of the Federal period began to displace natural forms in favor of Greek and Egyptian motifs.

Pineapple in colonial architecture

No one was a bigger fan of the pineapple than Virginia's William Byrd. For the James River door next to his impressive home at Westover, in 1730 Byrd ordered a carved door-surround from London. It featured a broken-scroll pediment with a pineapple in its center. Across the river from Westover, Brandon Plantation in Prince George County has a pineapple on the pinnacle of its pyramidal roof. Developed from a 1616 patent covering 7,000 acres on the James River, the site had a long and profitable trade connection with the West Indies, hence the prominence of the tropical pineapple.

Shirley Plantation, begun in 1725, has a geometric pineapple at the apex of its roof. Inside, two doorways feature pineapple woodwork dating from 1771. Over the bedroom door leading to the entry hall is a high-relief pineapple set inside a split pediment. And over the parlor door, is a pineapple between the volutes of a broken scroll. On the dining room mantle rests a silver tea caddy made in London in 1787. Its finial is an ivory pineapple with a little silver crown on top.

Lord Dunmore and the pineapple

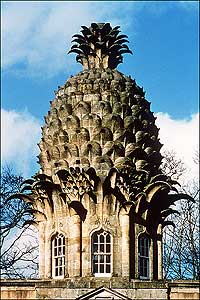

Scotland's relationship with the pineapple may have evolved because of the fruit's pointed similarity to the thistle. Pineapples were grown in Scotland as early as 1732. But the laurels for creating the largest and most enduring pineapple fall to Scotsman John Murray, Lord Dunmore, the last colonial governor of Virginia. At his estate near Airth he constructed a formal garden and garden house, which he transformed into an architectural folly – a 37-foot tall pineapple.

Pineapples today

Thus, by the time Colonial Williamsburg began decorating with fresh greenery and fruit in the 1930s, the pineapple was already a well established design element in architecture, ceramics, and art. It only stands to reason, then, that beautiful fresh pineapples would become the centerpiece for the creative decorations for which Colonial Williamsburg is known today.

Information for the following story excerpted from “The Hospitable Pineapple” by Michael Olmert, originally published in the Winter 1997-98 edition of the Foundation's journal, “Colonial Williamsburg.”.

Read more articles from the Foundation's journal, “Colonial Williamsburg”.