Page content

Equine Equanimity

It Takes a Special Sort of Horse

text by Ed Crews

photos by Dave Doody

Ben, an American Cream draft horse, does the heavy lifting, or pulling, for Joyce Henry of Colonial Williamsburg's coach and livestock program, perched on a water wagon in the Historic Area.

Not just any horse can pull a cart through Colonial Williamsburg's Historic Area. Obviously, the animal must be strong enough for the job. It must also be unflappable—steady enough to abide musket fire, squealing schoolchildren, and banging drums. High-strung, finicky animals do not fit in.

"We need horses who will be safe to handle in this environment," said Karen Smith, supervisor of stable operations for Colonial Williamsburg's coach and livestock department. "Our horses need to be comfortable with noise, barking dogs, people opening umbrellas, baby strollers rolling by. That's the type and the temperament we must have."

Any horse needs training. That takes time. "We're not in a rush," Smith said. "We're willing to wait to get a horse ready so we can have it with us working for years."

Colonial Williamsburg's are taught to accept humans. Gradually, the animals are taught to wear halters, to accept the hitching post, and to be led.

"At one year old, we get them used to voice commands. At two, we start to do long lines training. This means getting them accustomed to a bit and a surcingle on their backs. At three, we do some light riding and introduce them to poles, like the kind found on a cart or wagon. They don't start anything like work until they are four, and then it is pretty light," Smith said.

If all goes smoothly, by about age five a horse will be ready to pull heavy loads.

In the colonial period, Smith said, "just about everybody needed a draft animal for field work, for harvesting, and for hauling crops to market." Draft horses tended to be most popular, though not as common as oxen, in Virginia, a wealthy province where people could afford their upkeep. Less affluent New Englanders tended to prefer oxen.

"Oxen offered some options that horses didn't. If you raised them, then you could work them and ultimately eat them. Horses were only for transport, work, and pleasure," said Richard Nicoll, director of the coach and livestock department.

Mare and foal at play in the fields of grass and clover. American Creams Sarah and her offspring, Mary, take their leisure at lunch.

Nevertheless, we know little about specific types of animals found in the colony. "At the time, there was no neat division of horses by breed," Nicoll said. "People tended to describe horses by appearance or by use."

With the exception of some racehorses, colonial Virginians did not lavish attention on bloodlines the way modern breeders do. The current notion of breeds with distinct characteristics and abundant genealogical information took firm hold in America only in the nineteenth century.

"In the colonial period, they knew nothing about genetics," Nicoll said. "They did know that if you bred good with good, you tended to get good animals. And they knew that if you breed good and bad, you might improve the bad to good. But the knowledge we have now about genetics just wasn't available."

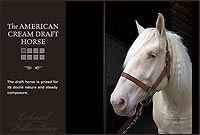

Nevertheless, for almost two decades a special line of horse, the American Cream draft horses, pulled Colonial Williamsburg Foundation wagons and plows or bore riders. Placid animals, they represented the kind of draft horse found in colonial Virginia during the 1700s, adding realism and beauty to educational efforts. In return, the foundation helped preserve for posterity what was becoming a vanishing breed.

The possibility of using American Cream draft horses in Williamsburg surfaced in the 1980s. "They have the perfect character for us," Smith said. "They're willing to please and are extremely people oriented. They are easily matched with other types of horses. Riders find them comfortable because of their smooth gait. Plus, they're strong, so they can pull a lot of weight."

Creams are attractive and large without being overwhelming. They have three basic colors: off-white, medium cream, and dark. By the time the Creams reach maturity at age five, they stand about six feet at the shoulder. The females typically weigh 1,500–1,600 pounds. Males often are 1,800 pounds or more. Most live twenty to twenty-five years.

Creams are the only draft horse breed to originate in the United States. The line is descended from one mare, Old Granny, which lived in Ellsworth, Iowa, during the early 1900s. Little is known about her parentage or ancestry.

In Colonial Williamsburg's stables, Karen Smith and Mary, here about four years old and a heft heavier than she was in the previous image.

Old Granny and her offspring gained a following in nearby communities, but the breed did not attract widespread attention until 1935. That year C. T. Rierson, owner of a stock farm in Radcliffe, Iowa, began acquiring horses to build a Cream breed. Rierson had a flair for promotion. He created the name "American Cream," talked up the animals, and showed them at county fairs.

But Rierson was running against the trend of history. Early in the twentieth century, horses provided power for American agriculture. By the 1930s, trucks and tractors were replacing the animals.

By the 1940s, breeders realized that without focused efforts the Cream would disappear. To prevent that, the American Cream Horse of America Association formed during 1944 in Iowa Falls, Iowa.

The association made steady progress until Rierson died in 1957. The group became dormant, and the breed slid into decline. By the 1980s, few Creams remained. Owners revived the association in 1982, hoping to save the breed. Today, the group is known as the American Cream Draft Horse Association.

Colonial Williamsburg joined the effort to get the horse power it needed and engage in another form of historic preservation. Creams came to Williamsburg in 1989, and the first foal was born the next year. Between then and 2006, when the breeding program had accomplished the goal of helping to preserve the bloodline and was suspended, ten Creams were born at the museum.

In the past twenty-four years, 500 American Cream draft horses have been registered. One remains in Colonial Williamsburg's care.

"Colonial Williamsburg has been one of the best things for these animals. Because of our visitors, our outreach is great," Smith said. "Visitors react to the American Cream draft horse just like they do to all animals. They're a strong point of interest for everybody who comes here. We get positive reactions from people who have animals.

"And we get positive reactions from city kids who come to Williamsburg and for the first time see chickens or cows or horses."

Ed Crews, a Richmond-based writer, contributed to the winter 2007 journal an article on Colonial Williamsburg's weavers.

Learn more: