Weaving, Spinning, and Dyeing

Dexterity and Detective Work

by Ed Crews

Turning fibers into cloth, weavers Sandy Gibb, Eileen Hammond, and Max Hamrick Jr. keep alive the eighteenth-century practices of the trade.

During the Revolution, Americans opened cloth manufactories similar to the Hamrick's (shown above), Gibb's, and Hammond's operation.

An encouragement to industry, this 1749 English engraving also shows something of eighteenth-century clothmaking.

Every piece of cloth made in Colonial Williamsburg's weave room has a story. Some, like those with bright red and blue patterns, reveal eighteenth-century tastes. Others, like the blue, orange, and black bed rug that resembles 1960s shag carpeting, suggest modern ideas are not at all new.

Max Hamrick Jr., Eileen Hammond, and Sandy Gibb know the stories and share them daily with Historic Area guests. Working in the lumber building behind the Wythe House on Palace Green, Hamrick, Gibb, and Hammond demonstrate spinning, weaving, and dyeing—textile production skills of the 1700s.

Then as now, Americans required fabrics for clothes, towels, sheets, blankets, sails, and dozens of other items made of wool, cotton, silk, linen, and hemp and bought them from textile manufacturers. Until the Revolution, British goods poured into the American market, and most of Williamsburg's citizens, from the governor to house servants, wore clothes made of English textiles.

English or American, weavers typically learned their trade through apprenticeship, which focused mostly on operating a loom, a machine that produced cloth by interweaving threads at right angles. Weavers had to know how to prepare the loom and how to run and to maintain it.

In England, fabric manufacture employed thousands. Such cities as Manchester and Nottingham were centers of an industry so large and specialized that weavers often made but one kind of cloth during their lives. Some labored in factories, which might have twelve to sixteen looms in a weave room. Other workers toiled at home on looms they owned or provided by a company.

During the 1700s, inventors steadily mechanized spinning and weaving. Each improvement increased speed and output, doomed hand production, and helped usher in the Industrial Revolution, ensuring a steady supply of relatively inexpensive British fabrics in the colonies.

Though England dominated the American market, the colonies had domestic producers, mostly in the northeast. Some southern planters had slaves make cloth, promoting self-sufficiency and keeping agricultural laborers busy off-season and in bad weather.

During the Revolution, when Americans could not get English goods, weaving became a necessity and a patriotic duty. Dozens of weaving "manufactories" opened to serve the American market, among them the Williamsburg Manufactory on Queens Creek in York County. Records suggest it employed a manager, weavers, spinners, and apprentices.

Hammond, Hamrick and Gibb demonstrate skills the manufactory required. For example, they spin, drawing fibers and twisting them tightly to form thread or yarn. During the 1700s, spinning was not an apprenticed trade but a domestic chore done with spinning wheels, which had come from India to Europe during the Middle Ages. Williamsburg's weavers demonstrate two types of these machines: a walking wheel for cotton and a Saxony wheel for flax, hemp, and wool.

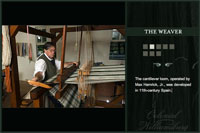

Colonial Williamsburg's weavers also turn out cloth with two types of looms that represent the types available to eighteenth-century Virginians. The smaller is a cantilever loom, developed during the eleventh century in Spain. The larger is a four-post box loom, created in England in the sixteenth century.

Also demonstrated at the Wythe lumber house is dyeing. Like weavers, 1700s dyers learned their craft through apprenticeship. They had to master mixing dye recipes and dyeing yarn. Because each type of fabric required a different approach, dyeing required knowledge and care.

Hamrick has made cloth for seventeen years in Williamsburg and spent another twenty-one working in the modern textile industry. He says dyeing and dye ingredients intrigue Historic Area guests. Many ingredients came from Spanish colonies in Central and South America. Eighteenth-century dyers used insects to produce red, indigo for blue, campeche tree heartwood for purple, walnut for brown, and turmeric for yellow. Because of their chemistry, many eighteenth-century dyes are these days deemed unsafe, but Hamrick uses harmless authentic formulas. His collection is so large he can produce any color known in the 1700s.

Eighteenth-century Williamsburg had a dyer. Not only did the shop dye clothes, giving last year's fashion a new life, but it did dry cleaning, spot removal, and fancy pressing.

"We can preserve, teach, revive, and reclaim this craft," Hamrick said. "Many trade secrets died when machines replaced craftsmen. Fortunately, lots of textile-related paperwork still exists. Using this, we can make cloth that nobody in the twenty-first century has ever seen." Some information comes from surviving fabrics, and close inspection can detect craftsmanship, quality, construction, and uses for the material.

"Some eighteenth-century cloth was meticulously done. Absolutely gorgeous. Material made for show is beautiful beyond modern imaging. It's hard to find a flaw in these goods. When you look at them, you know the work was done by a real craftsman. However, a lot of the ordinary cloth would never get out of the inspection room at a factory today," Hamrick said.

Hamrick has found that paintings can help with colors and that weavers' notebooks provide insights. Often, many weavers recorded their knowledge in code. Hamrick said that frequently that can be cracked, revealing a wealth of information.

Using this data, the weavers make a range of material. As visitors watch them work, one question is asked repeatedly: "Isn't that hard to do?" Not really, Hammond said.

"Learning how to weave a pattern is more fun than putting together a jigsaw puzzle," she said. "All the tasks here, even running the loom, are easier than learning to ride a bike. Setting up the loom takes time and focus. That's really like assembling a puzzle. At a glance, what we do seems complicated, but once you starting doing it, it's really easy."

Ed Crews, a Richmond-based writer, contributed an article on Colonial Williamsburg's basketmakers to the spring 2006 journal.