Page content

"Redefining Family" and the Becoming Americans Theme

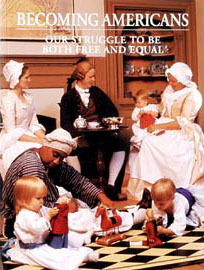

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s publication “Becoming Americans” explores the lives of real colonial Virginian families and how they approached life passages such as courtship and marriage, birth, childhood, and death.

During the colonial era, the institution of family evolved as political developments changed relationships between blacks, whites, and Native Americans. Families had to adapt as new leaders and principles redefined the status of every man.

Diverse Peoples

Native Americans, Africans, and British colonists held different cultural perceptions of the family. These understandings underwent profound alterations in response to the New World environment and in reaction to the other groups. The highly abnormal demographic conditions of the 17th century delayed and stunted the formation of family life, which was further reshaped when whites imported Africans to labor on their plantations. Encroaching settlement by Europeans and their slaves pushed the Indians from their traditional homelands.

Clashing Interests

Most Europeans considered Native-American family customs to be outlandish and debased. As patriarchal slave masters, whites intervened profoundly often peremptorily in the experience of their bondsmen imposed laws that relegated African-Virginians status inferiors.

Some members of the gentry resisted the changes that affected many families by the third quarter of the eighteenth century. The friction between Landon Carter and his son and daughter-in-law may be interpreted either as a generational disagreement over family relations or as an expression of individual preferences. At all times, variations in individuals' beliefs about what a family should be added diversity to early Virginia society.

Shared Values

Africans, Native Americans, and Europeans all placed a high value on children, family relationships, and kinship networks. As African-Virginians helped raise white children, lived and worked in close proximity to whites, and interacted with the master's family, accommodation between the races and an unconscious exchange of values took place. Living in Williamsburg could be a positive experience for both Sarah Trebell and her family's slave, Eady. Black and white Williamsburg children had some opportunity for schooling. After the Revolution, the adoption of a more egalitarian sharing of authority began to set a standard that was understood by all levels of society and is still perceived as important today.

Formative Institutions

While white masters began to accept the importance of slave families, neither the law nor the church sanctioned slave marriages. Legislation enforced the moral teachings of the Anglican church regarding acceptable social behavior and the treatment of dependents such as apprentices, servants, and slaves. Education was regarded as the chief means to pass one society's values and rules on to the next generation. The home was the unchallenged center for education, religious learning, and spiritual development.

Partial Freedoms

The gentry enjoyed more freedom in their family relationships by 1770, but these changing attitudes had no effect on slave families. Nor were they experienced in all white families, or even in all upper-class families. For example, although both husband and wife recognized the woman's role in a family, their lives continued to be narrowly defined and they were seldom educated to reach their full potential. The black family experience continued to lack stability. The opportunity for most black children in Williamsburg to receive some formal education faded when the Bray School closed its doors at the death of Ann Wager. A few masters such as George Wythe occasionally taught individual slaves to read. Few slave families responding to Dunmore's Proclamation gained their freedom. Native-American families continued to be confined to reservations in the East or were pushed to the limits of the frontier in the West.

Revolutionary Promise

Even before the Revolution, changes in white family values and experiences heralded transformations. Those families with skills, material goods, and knowledge of the appropriate behaviors increased their opportunities for social mobility. Racism and lack of opportunity meant that Native-American and slave families' full participation in the new republic remained an unfulfilled promise. A few slaves such as "Saul, the property of George Kelly Esquire," whose petition was brought before the 1792 Virginia Assembly were granted freedom for service to the Revolutionary cause. Virginia law recognized that some marriages were not successful, so limited divorce became available here and also in the rest of the nation. After the war, educating children to participate in the new republic contributed to the optimistic expectations for the United States. The transformed white American family became a cornerstone of the American character.

Buy it now.

Buy it now.