Page content

An Accidental Republic?

by Jack Lynch

When governance under the Articles of Confederation wheezed and wobbled, the states met in 1787 to draft a constitution giving a fresh start to the American experiment in self-rule, one that created a “republican form of government.” That meeting in Philadelphia has been one of the favored subjects of history painters. Here, an 1823 wood engraving depicts President Washington and the delegates.

James Madison and John Adams thought theorists’ ideas about the meaning of a republic were so inchoate that they bordered on incomprehensibility - portrait by Gilbert Stuart.

Where earlier historians had seen happenstance in the formation of the republic, Bernard Bailyn discerned purpose and coherence.

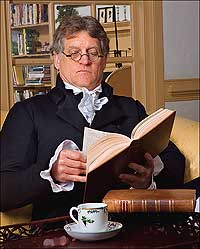

St. George Tucker, portrayed by Bill Weldon, studies his annotated Blackstone, for whom a republic was an inferior and even dangerous form of government. To Tucker, though, “peace and moderation is the spirit of a republic.”

Franklin Roosevelt commissioned Howard Chandler Christy’s version of the convention, for the Capitol rotunda in Washington.

The Constitution is clear: Article IV, section 4, decrees that “the United States shall guarantee to every state in this union, a republican form of government.” But what does “republican” mean? When, in Federalist 39, James Madison turned to history to discover “the distinctive characters of the republican form” of government, he said no satisfactory answer would ever be found. John Adams, another architect of the American republic, told Mercy Otis Warren in 1807, “There is not a more unintelligible word in the English language than republicanism. . . . I never understood it, and I believe no other man ever did or ever will.” Most writers agreed that it referred to a government without a king, but beyond that, there was little consensus.

Adams and Madison had reason to be baffled. There were people who used the word “republic” to include any government at all. Others used it as a synonym for “democracy,” as when Ephraim Chambers’s Cyclopædia defined a republic as “a popular state, or government. . . This amounts to the same with what we otherwise call a democracy.” Others drew distinctions between republics and democracies, though they rarely agreed on what the differences were.

Curious readers, though, could have turned to a tradition of republican political theory to understand what republicanism meant in history. Seventeenth-century England offered high-profile republican theorists: in Algernon Sidney’s Discourses concerning Government and James Harrington’s Commonwealth of Oceana, antimonarchical readers could find sympathetic accounts of republican governments. More influential was the poet John Milton, whose prose works The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates and The Ready and Easy Way to Establish a Free Commonwealth called for doing away with the monarchy. And these English writers were working in a line that stretches from the sixteenth-century Italian political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli through the Roman historian Livy, and ultimately to Aristotle.

For a long time, though, this tradition of republican theory was believed to be irrelevant to America’s republic. Most historians looked on the United States as a kind of accidental republic. The Framers were not students of republican political theory; they did not meditate on the nature of a republic in the modern world; they did not spend their time reading Livy, Machiavelli, or Harrington. The Founders, after all, were doers, not thinkers, and they established their form of government more or less by chance.

Americans, according to this version of the story, grew weary of English oppression. When they declared their break from Britain’s monarchical government, they suddenly realized that they had become a republic, and only then had to figure out what that meant. As the historian Cecilia M. Kenyon put it in 1962, “The Americans were not republicans in either a formal or an ideological sense before 1776. Within a few months, they were.” Their form of government was wholly new, not a development of the principles spelled out by earlier republican theorists.

It is true that, before the Declaration of Independence, writers in Britain and America reveled in attacks on republicanism. For many eighteenth-century writers, the word “republican” was a general term of abuse, an all-purpose put-down for any faulty political system. “The distinction of rank and honours,” wrote Sir William Blackstone in his Commentaries on the Laws of England, “is necessary in every well-governed state,” and he contrasted the well-governed and hierarchical Britain with the chaos of “a mere republic.” Blackstone’s contemporaries thought of England’s republican experiment as a failure: by the 1750s, most looked back on the Commonwealth, the years from 1649 to 1660, when England had no king, with horror. Other historical examples of republics fared no better: the Roman Republic gave way to the Empire; the Dutch and Venetian republics collapsed. An English commentator on the orations of Demosthenes said in 1757 that “Among all our different Forms of Government, there is not another so liable to civil Dissentions, as the Republican.”

Besides, many said that a popular republic was the form of government most likely to be taken over by a dictator—some argued paradoxically that republics and democracies were inherently tyrannical. Oliver Goldsmith, for instance, thought in 1764 that a republic was inherently more dangerous than even an absolute monarchy: “The oppressions of a Monarch,” he wrote in his History of England, “are generally exerted only in the narrow sphere round him; the oppressions of the governors of a republic, though not so flagrant, are more universal.” The result is that “the republican Despot oppresses the multitude that lies within the circle of his influence.” Writing in 1776, the Englishman John Fletcher pitied his “American fellow-subjects, who groan under the tyranny of republican despotism.” In 1778, English Bishop James Yorke told his flock not to envy their “unhappy and deluded colonies in America,” denouncing “the evil genius of arbitrary power” that had misled the Americans: they headed toward a “democratick despotism.”

Similar sentiments were heard across the Atlantic, even among those who had little patience for the Stamp Act and the Townshend Acts. William Drayton, who would become a prominent federal judge in 1790, fretted before the Revolution about “the exuberances of popular liberty.” Alexander McDougall, who would achieve fame as a Revolutionary general, worried that his country might be “verging to democracy,” and said, “God forbid that we should ever be so miserable as to sink into a republic!” It was probably the same fear that led many delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 to argue against the promise of “a republican form of government.” And Americans who did not criticize republicanism still praised the British Constitution, with its perfect balance of the monarch, the Lords, and the Commons. In 1759, Samuel Adams found the British system “the best model of Government that can be framed by mortals,” and two years later John Adams said, “No Government that ever existed, was so essentially free.” Surely, the argument went, no one so impressed by Britain’s monarchical system could want to toss it all out in favor of a “mere republic.” It was also obvious to many historians that early Americans would have agreed that a republic was impractical in a nation that sprawled for a thousand miles. As philosopher William Paley said, “a republican form of government suits only with the affairs of a small state. . . . He who represents two hundred thousands, is necessarily a stranger to the greatest part of those who elect them.” John Andrews published a book titled An Essay on Republican Principles, and on the Inconveniencies of a Commonwealth in a Large Country and Nation.

The most significant reason that historians assumed early Americans could not have been influenced by republican political theory, though, was that republicanism was known to be incompatible with the principles that dominated eighteenth-century American thought, Lockean liberalism. After all, John Locke’s fingerprints are all over the country’s founding documents, from the Declaration of Independence’s “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” to the Bill of Rights. But where liberalism emphasized rights, republicanism emphasized duties. Liberals said governments were instituted to protect the prosperity of the individual; republicans said they were to promote the general public good. Liberals thought the rights of individuals always trumped the demands of the state; republicans thought individual interests would often have to be sacrificed to the social good. Liberals believed that a healthy society would emerge from vigorous commerce; republicans despised luxury and advocated a Spartan ideal of self-denial. Most important, liberalism was supposed to be built on the foundations of unchanging human nature; republicanism, many believed, demanded a degree of personal virtue not to be found in the real world.

Progressive historians surveyed this evidence and said, with George M. Dutcher, that republican political theory was “clearly irrelevant to the discussion of the origins of republican institutions in America.” Dutcher went further: “Republican ideas,” he wrote, “were practically taboo.” In this, he was typical of his profession. It is hard to find the word “republicanism” in books on colonial America published before the mid-1960s. America may have ended up a republic, historians agreed, but it was a republic by default.

Beginning in the 1960s, though, scholars began exploring what Bernard Bailyn called the “ideological origins of the American Revolution.” Bailyn was among the first to say that republican theory informed colonial practice, and his conclusions surprised many. Where earlier historians had seen unschooled men of action stumbling upon republicanism, Bailyn saw a principled and systematic engagement with the history and theory of republicanism. And despite the attacks on democracies and republics in eighteenth-century writing, Bailyn identified another tradition of writing that held republics in high esteem. In short, Bailyn said, the American revolutionaries knew what they were up to, and their republican government was anything but accidental.

Since then a parade of historians have developed those insights. Bailyn’s student, Gordon Wood, laid out his account of the importance of republican theory in The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787, writing that the founding generation was steeped in the classical form of republicanism, and thoroughly familiar with Livy and the other republican writers in Rome. “For Americans,” Wood said, “the mid-eighteenth century was truly a neoclassical age—the high point of their classical period. At one time or other almost every Whig patriot took or was given the name of an ancient republican hero, and classical references and allusions run through much of the colonists’ writings, both public and private.” Others followed where Wood and Bailyn led, especially J. G. A. Pocock, whose Machiavellian Moment appeared in 1975. As Joyce Appleby put it, “Republicanism slipped into the scholarly lexicon in the late 1960s and has since become the most protean concept for those working on the culture of antebellum America.” Most historians now agree that the Founders knew their precursors well and thought of them often as they tried to develop their own republican government.

As historians began to explore this previously neglected ideological influence on the foundation of the United States, they discovered that many of the problems that kept republicanism neglected had been resolved in the eighteenth century. The English Commonwealth, for instance, so disparaged by mainstream writers in England, continued to attract interest from political writers whose works circulated widely in America. A large nation had always been considered ungovernable without a monarch, but now historians discovered colonists saying that even a continental republic was possible. And where many had argued that republics inevitably produced civil war, Williamsburg’s St. George Tucker wrote in 1803: “The spirit of monarchy is war, and the enlargement of dominion; peace and moderation is the spirit of a republic.”

Despite these reversals of conventional wisdom, though, one more serious task remained: linking republicanism to its long-time archrival, liberalism. Some of the most important historical debates during the past quarter-century have tried to reconcile these seemingly incompatible strands of early American thought. Some historians said Locke was never as important as he had been made out to be. For others, it was a matter of identifying liberal and republican factions struggling with one another in early American society. Others still have treated early American political thought as a blend of the two, picking up elements of each philosophy: Bailyn, for instance, found republicanism “interwoven with, yet still distinct from,” liberalism. Some have suggested it was a false dichotomy from the start, and our modern categories assume a clear distinction between the schools of thought that would not have been clear in 1770: Wood, for instance, has argued against any “sharp dichotomy between two clearly identifiable traditions.”

And a few historians have sought to reconcile the two into a single, especially American synthesis. Appleby, for example, has described a “liberal republicanism,” and Richard Dagger has written of a “republican liberalism.” This hybrid may be the most convincing explanation of America’s engagement with republican theory. It allowed early Americans to see the common good and the good of the individual not as mutually exclusive but as mutually reinforcing, and to blend two kinds of liberty—the freedom from oppression that marked republicanism, the freedom to act in accordance with liberalism—and to treat the abstraction called “the people” the same as the millions of real people who constituted it. Establishing their “republican form of government,” early Americans were neither ignorant of the past nor entirely subservient to it, and by blending two modes of thought they seem to have embraced the paradoxes that have shaped the direction of America ever since.

Jack Lynch, author of Becoming Shakespeare: The Unlikely Afterlife That Turned a Provincial Playwright into the Bard (Walker & Co., 2007), is associate professor of English at Rutgers University. He contributed to the spring 2008 journal the story “Robert Morris: Financing America’s Wars.”

Suggestions for further reading: