Page content

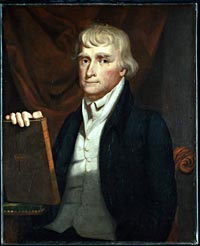

Thomas Jefferson, Son of Virginia

by Dennis MontgomeryStudent in Williamsburg, sage of Monticello, beau ideal of a new nation, he awes us still, 250 years after his birth

ALBEMARLE COUNTY'S freshman burgess was but two days launched on his legislative career, and already his pen had distinguished him. As Virginia's Assembly gathered at Williamsburg that May in 1769, influential Edmund Pendleton had steered to his colleague from the General Court the favor of a conspicuous maiden assignment. Pendleton's 26 year old associate, a bookish but charming lawyer, would draft the resolution specifying the points to be made in reply to Governor Botetourt's gracious opening address.

If this, the studious bachelor's first state document, was ceremonial boilerplate, it was courtly and inoffensive and widely if perfunctorily approved. It won him the honor of composing his second--the full, formal response. Always thinskinned and mortified by failure, this aloof, aristocratic, looselimbed, redhaired son of the upcountry may have been as relieved as he was gratified. But whatever hope he held for his composition vanished in the dismissive toss of Robert Carter Nicholas's periwig. The formidable chairman of the drafting committee, Nicholas judged the piece cautious and pinched, and dashed off a rewrite.

Thomas Jefferson long smarted from the slight. "Being a young man as well as a young member," he wrote 45 years later, "it made on me an impression proportioned to the sensibilities of that time of life."

It became a pattern of all his life: heady achievement undercut by humbling reverse, happiness taxed by humiliation. For now the drumbeat of events drowned out recrimination.

Affronted by resolves challenging Parliament's authority, Governor Botetourt dissolved the burgesses 10 days into the session. They repaired to the Ralegh Tavern's Apollo Room and listened to George Washington detail the absent George Mason's nonimportation proposals. With 88 other men, Jefferson inked his signature on articles of association and entered the lists of colonial resistance.

He was familiar with such talk, such proposals, these men, and this room. Nine years before, not quite 17, he had ridden in from his Rivanna River plantation, Shadwell, near the village that would be Charlottesville, to become a College of William and Mary scholar and a man about town. Already proficient in Latin, he could translate for himself the motto above the Apollo's mantel: "Hilaritas sapitentiae et bonae vitae proles--Jollity, offspring of wisdom and good living." The good life was already his and, if he could be a studious drudge, he had nothing against jollity either. There was opportunity enough in the city he called Devilsburg.

Born into the gentry April 13, 1743, Tom was the eldest son among eight children. His mother Jane was a Randolph, his father Peter a roughandready surveyor and a rising planter. Peter stood the boy to a classical education in Piedmont country schools and taught him to hunt and ride. When Peter died in the summer of 1757, he left his family proud memories and 7,500 hilly, slave-tended acres. But Tom treasured his education most.

Peter left guardians, too, though his son discounted them. Years later, to a grandson entering college, Jefferson wrote:

When I consider that at fourteen years of age the whole care and direction of myself was thrown on myself entirely, without a relative or a friend qualified to advise or guide me, and recollect the various sorts of bad company with which I associated from time to time, I am astonished that I did not turn off with some of them, and become as worthless to society as they were. From the circumstances of my position, I was often thrown into the society of horseracers, cardplayers, foxhunters, scientific and professional men, and of dignified men; and many a time have I asked myself, in the enthusiastic death of a fox, the victory of a favorite horse, the issue of a question eloquently argued at the bar, or in the great council of the nation, "Well, which of these kinds of reputation should I prefer--that of a horsejockey, a foxhunter, an orator, or the honest advocate of my country's rights?"

In the course of making up his mind, Tom indulged himself. "While at college," a descendant said, "he was one year quite extravagant in his dress, and in his outlay on horses." Having overspent his share of family income, he offered to make it good. His guardian replied, "No, no; if you have sowed your wild oats in this manner, Tom, the estate can well afford to pay your expenses."

The expenses of his Williamsburg days included sums for bumbo, Dutch dancing and singing, Peter Pelham's organ playing, and a few shillings wagered on backgammon and cross and pile. He paid to see plays, alligators, a tiger, puppets, a 1,000 pound hog, and a man ride three horses at once. He took refreshment at the coffeehouse, no doubt gawked at the town madman Selim, bought a fiddle and fiddle strings at Hornsby's. A more important purchase was an architecture book bought from a cabinetmaker near the college gate. Tom bought lots of books.

He caroused with the boys, flirted with the girls, studied late into the night, and fixed his eye on Rebecca Burwell, a beautiful orphan whom moony 19 year old Tom petnamed Belinda. For months his adolescent letters--embarrassing now to read--were full of Belinda. His self-conscious infatuation soon embarrassed him, too. When he gathered up his courage to approach her, Tom made a fool of himself. He wrote "in the most melancholy fit that ever any poor soul was":

Last night, as merry as agreeable company and dancing with Belinda in the Apollo could make me, I never could have thought the succeeding sun would have seen me so wretched as I now am. I was prepared to say a great deal. I had dressed up in my own mind such thoughts as occurred to me, in as moving language as I know how, and expected to have performed in a tolerably creditable manner. But, good God! when I had an opportunity of venting them, a few broken sentences, uttered in great disorder, and interrupted with pauses of uncommon length, were the too visible marks of my strange confusion.

Though he commanded the ornate English of the era and easily acquired Greek, French, Italian and Spanish, Jefferson never mastered his tongue. Rebecca found a life companion more fluent in the language of love, and the abashed young Jefferson entertained fewer distractions in his recently begun studies in the law.

His scholarship was less the product of the classroom than the extramural inspirations of a maverick professor who recognized and cultivated frecklefaced Jefferson's budding genius. A torchbearer of the Scottish Enlightenment, Dr. William Small taught natural history. Under his tutelage, Jefferson toiled with the triumvirate of Bacon, Newton, and Locke, and gained admittance to the charmed circle of Governor Francis Fauquier. At the Palace with Small and George Wythe, he dined with three of Virginia's best minds, feasted on science and philosophy, bowed the fiddle, debated ethics, and polished his manners. They quickened his interests in the world, interests he would apply to the heavens, weather, music, mathematics, paleontology, surveying, gadgets, linguistics, education, literature, physics, metaphysics, architecture, art, history, antiquities, medicine, natural law, religion, government, and scientific agriculture. They opened his mind.

He quit the troubled college to read the law for Wythe on Palace Green in 1762. Small, Jefferson said, probably fixed the destinies of his life, but with the professor's departure for England in 1764, Wythe--"the honor of his own, and the model of future times"--became his mentor.

To Jefferson, it seemed Wythe's "virtue was of the purest tint; his integrity inflexible, and his justice exact; of warm patriotism, and, devoted as he was to liberty, and the natural rights of man, he might truly be called the Cato of his country, without the avarice of the Roman; for a more disinterested person never lived." He was temperate, regular, modest, chaste in language, logical, and learned. Commuting from Shadwell with bundles of books, Jefferson lavished five years on study under Wythe and emerged in 1767 among the elite of the lawyers, a man of polished politeness, taste, and, to all appearances, unblemished behavior. He had become a community leader, too, making his first public service the clearing of the Rivanna for commerce.

Thinking on what he learned in his 20 Williamsburg years, an aging Jefferson described the city as "the finest school of manners and morals that ever existed in America." His knowledge of prominent men and events had grown apace, too.

Standing at the door of the lobby of the House of Burgesses a Thursday in May of 1765, Jefferson and John Tyler heard Patrick Henry deliver his speech against the Stamp Act. "He appeared to me to speak as Homer wrote," Jefferson said.

Tom met Henry at Christmas in 1759 on the Dandridge plantation. Jefferson's estimate of his mercurial countryman was equivocal; experience supported his reservations. Enmity lay ahead, but in these days they worked in harness in the Assembly and the courtroom.

In his eight years of practice, Jefferson handled more than 940 cases. His specialty was the caveat, a touchy branch of land patent litigation. He interested himself in the spicy divorce Blair v. Blair, pleaded for inoculation suit defendants, and took, pro bono, a hopeless case for a mulatto slave's manumission.

He had thought of raising a house in Williamsburg but spent his homebuilding energies at Shadwell, and he may have shared his growing architectural talent with others. His idol was Palladio, the Italian classicist. Jefferson tinkered with the family farm but began to plan a place for himself atop the foothill above. He called it, after the Italian for little mountain, Monticello. Site work began in 1768.

Jefferson was at the Charlottesville courthouse the afternoon of February 1, 1770, when a slave came to tell him Shadwell was burning. Only his fiddle had been saved. He moved into Monticello's only building, a one room dependency, alone in November. It appears that the next month he found a lady with whom to share it, a handsome young widow named Martha Wayles Skelton.

Devoted to the violin--he practiced three hours a day--Jefferson studied under Williamsburg music teacher Francis Alberti. It is said that the widow Skelton took harpsichord lessons from Alberti, and, perhaps, at his house she and Jefferson met. They wed January 1, 1772. She was 23, he 28. At month's end they rode up his snow covered little mountain in the night, and Jefferson skipped February's Assembly. Their years were halcyon.

Six feet two and a half inches tall, thin, squareshouldered, strong, Jefferson was straight as a gun barrel. He neglected fashion in clothes and hair, never lost a tooth, but seldom smiled or showed any expression. Stiff with strangers and acutely sensitive to personal slights, he found nothing so goading as to be contradicted in company by his wife. Under stress he was prone to migraines that lasted weeks. He liked to toss off bits of his learning, but when he spoke in public his voice was hoarse and guttural.

He ate little meat, and then as a condiment for his vegetables. Peas were his favorite. He did not drink strong wines or spirits, rose by dawn, and left his room by eight after bathing his feet in cold water.

Monticello rose as the family grew--the first baby came September 27--and the Jeffersons were often off for Williamsburg. He drew plans for expanding the college, and, perhaps now, for remodeling the Palace. He penned legislation, gave legal opinions, and sat on Virginia's Committee of Correspondence. When Martha's father died, the Jefferson holdings grew to 10,000 acres with 135 slaves. He bought Natural Bridge and traveled to his new lands at Poplar Forest. And he became a leader at the ad hoc meetings of the radicals in the Assembly opposed to British oppression.

Jefferson, Henry, Mason, Richard Henry Lee, and Francis Lightfoot Lee gathered the night of May 23, 1774, in the Council Chamber, and Jefferson outlined a protest--a day of fasting, humiliation, and prayer--against the Port of Boston's closing. They persuaded moderate Robert Carter Nicholas himself to introduce the resolution. It passed, Governor Dunmore dissolved the House once more, and again its members repaired to the Ralegh. This time they proposed an annual Continental Congress and a boycott of such imports as tea, and Jefferson began laboring over his first literary contribution to the Revolution.

For Albemarle County he wrote resolves attacking Parliament's usurpations. From these he elaborated a document for the first Virginia Convention, instructions to its congressional delegates. "If it had any merit," Jefferson said, "it was that of first taking our true ground, and that which was afterwards assumed and maintained."

JEFFERSON early discovered the ploy of working through others. Just as he had lately persuaded Nicholas to front for the radicals, he had before prevailed upon friends to introduce his initiatives. Now, through what bears earmarks of a convenient illness, he absented himself from the August convention and aimed to have Henry or Speaker Peyton Randolph bring forward this argumentative, eloquent work. Henry failed him, but Randolph laid the document on the table for inspection.

The Assembly rejected it. Too extreme. Saving what they could, friends took it to Williamsburg's Clementina Rind for printing as A Summary View of the Rights of British America. A historical justification for colonial resistance, the pamphlet is strong on rhetoric, weak on history. It ought to be remembered for two sentences in the concluding paragraph--"The whole art of government consists in being honest" and "The god who gave us life, gave us liberty at the same time; the hand of force may destroy, but cannot disjoin them." And it propelled Jefferson into the authorship of the Declaration of Independence.

In March, Jefferson attended the second Virginia Convention. It met in a Richmond church that rang with Henry's defiant "Give me liberty" oration. On its last day it elected Jefferson a deputy congressional delegate in case its president, Randolph, had to attend to more important duties in Virginia's Assembly. In the aftermath of the Powder Magazine disturbances in Williamsburg, Dunmore called an Assembly for June 1. Randolph had to return.

Jefferson spent 10 days in the House before leaving for Congress, helping draft a rebuff of Lord North's conciliatory proposals. He reached Philadelphia just ahead of the news of Bunker Hill. As Washington rode for Boston, Jefferson was recruited to rewrite John Rutledge's "Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms." Another fiasco. This time Pennsylvanian John Dickinson, a man of more literary pretension than Nicholas, insisted on rewriting Jefferson.

The Virginian's next assignment, Congress's reply to North, went smoothly, nevertheless, and he left Philadelphia in August for another Richmond convention and election as congressman in his own right.

In May of 1776 he departed Monticello for his third session, arriving at Pennsylvania's State House the day Virginia's legislature directed its delegation to move for independence. The instructions arrived May 27, and 11 days later Richard Henry Lee obeyed them. But the time was not ripe. While the delegates argued, they appointed a committee to draft a standby announcement. Jefferson, 33, chaired it, seconded by John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman and Robert Livingston. The first question was who would write. Adams, adept as anyone at making others his instruments, favored Jefferson.

Jefferson asked why Adams could not do it. "Reasons enough," Adams said. Jefferson asked, "What can be your reasons?" Adams said, "Reason first: You are a Virginian, and a Virginian ought to appear at the head of this business. Reason second: I am obnoxious, suspected, and unpopular. Reason third: you can write 10 times better than I can."

The Virginian returned to his rented rooms on the second floor of brickmason Jacob Graff's threestory home and sat down in the parlor. Before him was a portable writing desk made, to Jefferson's specifications, by cabinetmaker Benjamin Randolph. And he began: "When in the Course of human Events . . . ." In 1776 the meat of the Declaration was the list of charges against the king; for the Preamble he aimed at nothing more original than an expression of the American mind.

His mind was divided. In Williamsburg the Virginia Assembly debated Mason's proposed state constitution. Jefferson, deeming that more important work, in mid-June tardily sent to Williamsburg a constitution of his own.

He presented his Declaration, with minor committee changes, June 28 to the Congress. Independence came July 2, then debate on Jefferson's document. It was an excruciating experience. Every writer needs an editor, but Jefferson had more than 50 tampering with his handiwork, questioning his commas, slashing away a quarter of his words. He sat silently, his habit in legislative bodies, but the sensitive Virginian was displeased to the end of his days. And though on his tombstone he listed the Declaration as first of three signal achievements, he saw that friends and posterity got copies of his original.

When Jefferson spoke of his country, he usually meant Virginia, where his first loyalties stood. By October 7 he and Martha were staying in Congressman Wythe's vacant Williamsburg house. On the 11th Jefferson refused the United States' appointment as ambassador to France and began introducing bills. The first would establish courts, the second would end entails, the third would move the capital inland. On the 24th he proposed revising all the state's laws and on November 5 he and a committee began. For three years he would appear as the author or chief advocate of more bills than any other member of the Assembly.

He ended primogeniture, helped ban importation of slaves, and put forward his Statute for Religious Freedom--the second achievement on his tombstone. He proposed a general education bill, proportionment of punishments to crimes, and reformation of the flagging college--so many bills they formed a reservoir of legislation tapped for years. He was intent on "forming a system by which every fibre would be eradicated of ancient or future aristocracy, and a foundation laid for a government truly republican."

On June 1, 1779, the Assembly elected him governor--a job that began awkwardly and ended in finger pointing. It took two votes to squeak past a close friend for what amounted to the enervated chairmanship of a dispersed executive committee. Virginia had daunting problems; Governor Jefferson, 36, had little power to solve them. There was dissension, profiteering, malingering, military naiveté, and dizzying inflation.

His two terms were unencumbered by singular success. But he made Richmond the capital, expanded William and Mary's curriculum, saw its law school established in the old Capitol under Wythe, provided public library facilities, preserved and annotated historical documents, and researched a dozen fields to answer a French naturalist's questions.

Nevertheless, Benedict Arnold chased the government out of Richmond in January 1781, and Cornwallis did it again in May. Governor Jefferson was faulted for vacillating in the face of Arnold's advance, but on both occasions he eventually reacted with vigor to save what he could. The legislature adjourned to safer Charlottesville, and Jefferson followed.

His administration expired June 1. His intentions about a third term were unclear, and the legislature chose no replacement. Confusingly, Jefferson conducted executive committee meetings after his term.

British Colonel Banastre Tarleton arrived June 4 with 180 dragoons and 70 cavalry to clarify matters. Forewarned by the heroic militiaman Jack Jouett, most of the lawmakers escaped. Jefferson lingered on his mountain, entertaining breakfast guests and getting his family off, until the invaders were on its flank.

Within a week his competence was questioned (15 years later he would be accused of cowardice). Delegate George Nicholas, Robert Carter Nicholas's son and Henry's ally, introduced a resolution "that at the next session of the Assembly an inquiry be made into the conduct of the Executive of this State for the last twelve months." It was the rock bottom point of Jefferson's public service. Jefferson held his predecessor Henry responsible for the effrontery.

Adding injury to insult, his horse Caractacus threw him, and Jefferson spent much of the summer at Poplar Forest nursing a sprained arm. From there he asked Nicholas for a bill of particulars and assembled from memoranda his only book, Notes on the State of Virginia.

Jefferson finagled an Assembly seat and appeared in December to defend himself. For three days he stood answering charges point by point. On the 19th the legislature passed a resolution of sincere thanks "for his impartial, upright, and attentive administration whilst in office," and declared "in the strongest manner . . . the high opinion which they entertain of Mr. Jefferson's ability, rectitude, and integrity, as Chief Magistrate of this Commonwealth."

He may have wondered at the phrase "whilst in office;" he was certain he wanted never to serve in government again. Reelected to the Assembly, he petulantly refused to serve. He devoted himself to his home, his farms, his affairs, and his family. Spring brought a French visitor, FranHois Jean, Marquis de Chastellux, who found Jefferson at his best. Chastellux wrote:

Let me describe to you a man not yet forty, tall, and with a mild pleasing countenance, but whose mind and understanding are ample substitutes for every exterior grace. An American who without ever quitting his country, is at once a musician, skilled in drawing, a geometrician, an astronomer, a natural philosopher, legislator, and statesman . . . and it seems as if from his youth he had placed his mind, as he had done his house, on an elevated situation, from which he might contemplate the universe. . . . We may safely aver that Mr. Jefferson is the first American who has consulted the arts to know how he should shelter himself from the weather.

Mrs. Jefferson was expecting again, and May 8 bore the child, her seventh in two marriages. Each birth took a larger toll, emotionally and physically. All but two of the first six babies died in infancy or early childhood, and her recuperations grew more difficult. September 6, 1782, after four months of constant attention, anxiety, and selfaccusation, Jefferson recorded in his account book, "My dear wife died this day at 11:45 a.m."

By family lore, he promised Martha her children would have no other mother, and penned with her a romantic passage from their favorite book, Tristam Shandy. He left her deathbed in a stupor and fainted. Driven by grief, he paced his room three weeks, admitting only his oldest daughter, stopping only to throw himself in exhaustion on a pallet. He emerged finally to ride wildly for hours through the forest, day upon day.

Now his home was empty and he was at loose ends. Congressman James Madison, an intimate, contrived to have Jefferson appointed a peace commissioner to England. With alacrity the widower returned to public life, accepting the job immediately and leaving for Philadelphia a year to the day after he defended his governorship.

Word of a treaty arrived before Jefferson sailed, and his trip was shelved. He busied himself writing another constitution for Virginia that, among other things, would have put slavery in the course of extinction but required deportation of all Virginia blacks. It was mothballed.

In October 1783 he was back in Congress, embarking on his longest period of service to the nation. He wrote proposals on decimal currency and schemes of weights and measures, drafted plans for government and statehood of the western territories, and won a foreign appointment.

He left Boston for France on July 5, 1784, to be minister plenipotentiary for Europe, then succeeded Franklin as ambassador to France. He negotiated, bought books, set up elegant housekeeping, waited at court, toured, began work on an improved moldboard for the plow, and wooed with abandon another man's wife, Maria Cosway. From Paris's Halle aux Bleds he took the model for Monticello's dome, and on a trip to England to see Ambassador John Adams he attended a levee of George III and his queen. The king turned his back. Jefferson said, "It was impossible for anything to be more ungracious than their notice of Mr. Adams and myself. I saw at once that the ulcerations in the narrow mind of that mulish king left nothing to be expected on the subject of my attendance."

The erratic Mrs. Lucy Ludwell Paradise, a Williamsburg lady living in London, gave him a warmer reception. She fell in love with him and, when her husband died, wanted Jefferson for a replacement.

As the tumbrels of the French Revolution began to roll, Jefferson returned to America, reaching Norfolk on November 25, 1789, where he read that President Washington had nominated him secretary of state. While he considered, he caught up. Learning Wythe had quit the College of William and Mary in disgust, he wrote to his secretary William Short that "it is over with" the college unless Wythe could be induced to return. He visited his way up the Peninsula and passed, apparently for the last time, through Williamsburg. Though he reached Monticello before Christmas, he waited until Valentine's day to accept Washington's offer.

He wished he hadn't. His relations with Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton turned ferocious, and he grew to doubt Washington. Anonymous blasts and counterblasts enlivened the newspapers. Jefferson suspected his opponents of English royalism and called them monocrats. They called him a democrat--an ugly word then--and a lackey of the French. In 1792 he decided to resign but stayed until December 1793.

In the meantime he was planning to build Monticello over. "Architecture is my delight," he said, "and putting up and pulling down, one of my favorite amusements." The remodeling was so thorough that the threestory house that stands now on the mountain amounts to the second. The handsome but impractical dome may have been intended for billiards, an amusement Virginia outlawed before remodeling was finished in 1809. It was mostly used as a storeroom, and still is.

As the project began, he refused Washington's request to be ambassador to Spain: "No circumstances, my dear Sir, will ever more tempt me to engage in anything public." Nevertheless he acquiesced in his nomination for president in 1795 and--as the electoral system then disposed of runnersup--his election as Federalist John Adams's Republican Vice President.

Before leaving for Philadelphia, he wrote of the monocrats to a friend: "It would give you a fever were I to name to you the apostates who have gone over to these heresies, men who were Samsons in the field and Solomons in the Council, but who have had their heads shorn by the harlot Enland." When the letter reached the press in 1798, it opened a breach with Washington that only widened.

Jefferson regretted the publication, not the statement. He believed "a fair and honest narrative of the bad, is a voucher for the truth of the good," and he tried for evenhandedness in his assessments of character. For example, a few years later Jefferson wrote that Henry was the greatest orator, good humored, and understood the human heart. "His judgement in other matters," Jefferson said however, "was inaccurate; in matters of law it was not worth a copper: he was avaricious and rotten hearted. His two greatest pleasures were the love of money and of fame: but when these came into competition the former predominated."

By 1798 he had soured, too, on Adams, and secretly wrote, to disguise the disloyalty, the Kentucky Resolves, against his administration's pernicious Alien and Sedition Acts. Madison turned them into the Virginia Resolves. Between them they suggested nullification and interposition.

JEFFERSON openly sought the presidency as the elections of 1800 neared, but his secularism, wealth, and freethinking--he called himself "a rational Christian"--alarmed pious Northerners. The Connecticut Courant asked readers: "Do you believe in the strangest of all paradoxes--that a spendthrift, a libertine, and an atheist is qualified to make your laws and govern yourself and your posterity?"

Though he admired Christian ethics and compiled the Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, Jefferson denied miracles. He abhorred religious bigotry and, in the wake of clerical attacks, wrote, "I have sworn upon the altar of God eternal hostility to every form of tyranny over the mind of man."

The election ended in a tie with Aaron Burr, and it took the House of Representatives 36 ballots over six nervous days to elect a winner. On March 4, 1801, Jefferson, 57, walked from his boarding house at New Jersey Avenue and C Street to take the oath at the Capitol.

During two presidential terms he sent Lewis and Clark to explore the west and doubled the nation's size with the Louisiana Purchase. He ran for a second term to vindicate his actions in the first, but he left office under the cloud of the Embargo, an administration measure intended to curtail British aggression but which devastated American shipping and trade.

Regularly on the road to Monticello, President Jefferson did what he could to maintain his private affairs, and started his retirement hideaway at Poplar Forest. The house turned out well, but his finances suffered, and he spent $11,000 more on the presidency than he earned. He was anxious to leave government. "Never," he said, "did a prisoner released from his chains feel such relief as I shall on shaking off the shackles of power." On March 11, 1809, he left Washington for good with a new endeavor in mind, the creation of a university.

Jefferson had a weakness for educational schemes. In 1779 he tried, and failed, to make a modern university of his alma mater, introducing his Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge. By 1794 he was thinking of an upcountry university to replace the College of William and Mary. In 1800 he asked Joseph Priestley's advice on subjects to be taught at a university and let it be known he had given up on the Williamsburg college. Soon after retirement he first used the phrase "academical village," denoting his concept of a college as a close community of students and professors. He had time at last to think of such things. He wrote:

I am retired to Monticello where, in the bosom of my family, and surrounded by my books, I enjoy a repose to which I have been long a stranger. My mornings are devoted to correspondence. From breakfast to dinner, I am in my shops, my garden, or on horseback among my neighbors and friends; and from candle light to early bedtime, I read. . . . I talk of ploughs and harrows, of seeding and harvesting, with my neighbors, ad of politics too, if they choose, with as little reserve as the rest of my fellow citizens, and feel, at length, the blessing of being free to say and do what I please, without being responsible to any mortal.

His correspondence with John Adams, disrupted by political dispute, resumed. Those letters were among the few he did not begrudge in retirement, though all his life he answered mail faithfully, and about 60,000 of his personal letters survive. From them and other works he can be quoted on nearly any side of most questions.

His passion for gardening bloomed. "I have often thought that if heaven had given me choice of my position and calling," he wrote, "it should have been on a rich spot of earth, well watered, and near a good market for the productions of the garden. No occupation is so delightful to me as the culture of the earth, and no culture comparable to that of the garden. . . . But though an old man, I am but a young gardener."

In the wake of the War of 1812 two determinative events of Jefferson's old age unfolded. An economic depression that would ruin him began, and he drafted his plan for the Central College of Virginia. Strapped for cash, he offered to sell his 10,000volume library, America's best, to replace the congressional collection destroyed by the British when they burned Washington in August 1814. The proceeds, $23,950, reduced his debts by half but were only half the replacement value.

In winter he reduced to paper his college plan, and, as 1815 began, he sent it to a lieutenant in the Virginia legislature. It took a year to pass a bill, but he had now government backing. Monticello overseer John Bacon was there July 18, 1817, when, with a ball of twine from Old Davy Issac's store, they staked out the first building on 200 acres of worn-out farmland a mile west of Charlottesville.

"Mr. Jefferson looked over the ground some time and then stuck down a peg," Bacon said. "He stuck the very first peg in that building, and then directed me where to carry the line, and I stuck the second. . . . He had a little rule in his pocket that he always carried with him, and with this he measured off the ground and laid off the entire foundation, and then set the men at work." In October they laid the cornerstone for pavilion Number 7, the next to the last in the west rank.

"While the buildings were being erected, his visits to them were daily," a descendant said, "and from the northeast corner of the terrace at Monticello he frequently watched the workmen engaged on them." Jefferson called the school "the last of my mortal cares and the last service I can render my country."

The University of Virginia was chartered in January 1818, and in March Jefferson was elected rector. Hamstrung for money, construction proceeded slowly, but it proceeded inexorably.

The College of William and Mary, its enrollment threatened, lent a financially desperate Jefferson $24,705 in 1823 to forestall bankruptcy, and may have expected gratitude. As he began to recruit faculty in 1824, he flexed legislative muscle to block the college's hopes to move to Richmond and open a medical school. At year's end he proposed its endowment be used to establish intermediate schools in Richmond and Williamsburg. In January he sent to the capital "A bill for the discontinuance of the College of William and Mary and the establishment of other colleges in convenient distribution over the state."

ON MARCH 7, 1825, the University of Virginia opened with 30 students. It was Jefferson's aim that "this institution will be based on the illimitable freedom of the human mind. For here we are not afraid to follow truth wherever it may lead." It was the third achievement inscribed on its founder's tombstone, and, by his hand, a gem. "The form and distributions of its structure are original and unique," he said, "the architecture chaste and classical, and the whole well worthy of attracting the curiosity of a visit." With its Rotunda--formed on the model of a sphere within a cylinder--its terraced Lawn, and its procession of classical facades, it is among the finest examples of American architecture.

His last project well on its feet, Jefferson's health began to fail. He had long had rheumatism, nursed an arm broken in 1822, and now developed prostate trouble. He took ever increasing doses of the opiate laudanum for pain. Lafayette visited in August; they knew they would see one another no more. His spirits sagged.

In October student disturbances tarnished the reputation of his university, and some of the painstakingly assembled faculty threatened to quit. A chagrined Jefferson attended a peacemaking meeting, tried to speak, and found he could not.

His debts were so heavy--$107,273.63 in the end--a lottery with all of his lands was the only way out. Only Monticello was to be saved. But the lottery failed, and the homeplace was lost. At mid-March of 1826 he wrote his will, and in early June he made his last campus visit, to see a capital installed on a Rotunda column.

He sent June 24 for his physician, Dr. Robley Dunglison, and wrote his last letter. It was to Roger Weightman, declining an invitation to the city of Washington's celebration on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. In part it said, "All eyes are opened, or opening, to the rights of man. The general spread of the light of science has already laid open to every view the palpable truth that the mass of mankind [have] not been born with saddles on their backs, nor a favored few booted and spurred, ready to ride them, by the grace of God."

Stuporous, he slipped into a troubled sleep July 2. Grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph was with him. Jefferson awoke the evening of the third, thinking it was morning, and said, "This is the Fourth of July." At 9 p.m. he refused more laudanum. "No, doctor, nothing more." Randolph said,

The omission of the dose of laudanum administered every night during his illness caused his slumbers to be disturbed and dreamy; he sat up in his sleep and went through all the forms of writing; spoke of the Committee of Safety, saying it ought to be warned. . . . At four a.m. he called the servants in attendance with a strong and clear voice, perfectly conscious of his wants. He did not speak again. . . . He ceased to breath, without a struggle, fifty minutes past meridian--July 4th, 1826. I closed his eyes with my own hands.

Colonial Williamsburg Journal Vol. 15, No. 3 (Spring 1993) p. 14.