Page content

"The Best Is Not Too Good For You"

Williamsburg Celebrates Seventy-Five Years of Collecting at New York's Forty-Seventh Winter Antiques Show

by Sophia Hart

Hanz Lorenz

The sentiment that encircles the rim of this seventeenth-century pot provided the exhibition's name.

Hans Lorenz

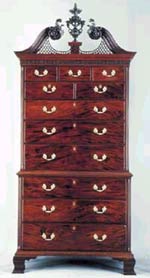

Crafted in 1775 by Philadelphia's Thomas Affleck, the mahogany chest-on-chest below is from the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum.

Dave Doody

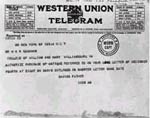

The Ludwell-Paradise House is the antique that Rockefeller's telegram, above, authorized Goodwin to buy.

Hans Lorenz

Collet's 1763 painting High Life Below Stairs captures an amusing domestic scene and shows us a room full of eighteenth-century objects, clothing and tools.

Hans Lorenz

This mahogany tall clock in the Colonial Williamsburg collections was made in Rhode Island by William Claggett about 1745.

Hans Lorenz

Made in New Hampshire during the 1920s, the Banjo Chair can be found in the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller FolkArt Museum.

Hans Lorenz

The fragment of a soap-stone pipe, recovered from a tavern site, brings American Indians into our picture of colonial Williamsburg.

About 315 years ago, sometime after the English deposed James II it seems, a potter in Staffordshire, England, fashioned a three-handled slipware cup, decorated it in relief with impressed squares, and brushed on the words: “Drink Well: God Bless King William.” Most likely, the potter intended it as a presentation piece—something to sell to a group of drinking companions eager to toast the health of their new sovereign. Proud enough, apparently, of his handiwork to advertise, or maybe merely vain, the potter added: “Thomas Simpson Made this Cup.” Acquired in 1956, it is but one of more than sixty thousand decorative art objects in the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, objects assembled to tell the story of colonial Chesapeake society and the Anglo-American world beyond. Picking it up for a better look, your fingers close on the past, taking by the handle the distance between yourself, and William of Orange, and potter Thomas Simpson.

Nevertheless, it is just a cup, another item of material culture in a mercantile empire and more fully appreciated from a scholarly than a sentimental perspective. Besides, not far away rests a larger, older example of this genre of explicative slipware, a jug with an abstract decorative border, probably thrown in Latton Parish, Essex, about 1650, and acquired by the foundation in 1960. Its inscription says: “The Gift is Small. Good Will is All. When Thes You See, Remember Me. Be Mery and Wies.” If the identity of “Me” is lost to time, the piece still discloses that some sentiments are as timeless as they are trite, and that seventeenth-century people yet enjoyed freedom from the fetters of uniform spelling.

At all events, we’re here to see another piece altogether, a two-handled brown and white affair decorated with tulips and rosettes, also made in Staffordshire, in 1697. To give you an idea of how long ago 1697 is, that’s the year George Washington’s grandfather Lawrence died and two years before Williamsburg became the capital of the Virginia colony.

This cup is an example of a bragget-pot, a term that has to do with the refreshment this broad, squat vessel—more than ten inches wide and about six inches tall—was fired to receive. From such cylinders late-seventeenth-century Englishmen drank a concoction of ale and honey fermented with spices, a treat they called bragget and drank on Bragget Sunday, which the reference books report falls in mid Lent.

The books don’t mention how volatile bragget was, but, from the looks of the double-grip construction of this piece, the stuff required both hands, and, like a tippler’s, the words that ring the rim stammer a little as they go tripping on a “T.” It says: “The Best Is Not T Too Good for You. BB RF 1697.”

Whether the initials BB and RF represent the potter, the presenter, the presentee, or some of them, or all of them, is a question to be investigated. But it takes only a glance to discover the appropriateness of such a pot for the signature object in the foundation’s loan exhibition at the Forty-Seventh Winter Antiques Show in New York’s Seventh Regiment Armory.

Entitled, “The Best Is Not Too Good For You:” Colonial Williamsburg Celebrates 75 Years of Collecting, the exhibition features forty-eight treasures from the foundation’s collections.

"Colonial Williamsburg’s educational mission of preserving America’s rich cultural past for future generations is a perfect match for the Winter Antiques Show,” said Ronald L. Hurst, Colonial Williamsburg’s chief curator and vice president of collections and museums. “Visitors to the show will appreciate not only the great beauty of the objects they will see on display, but also the allure of the material past—what these objects teach us about the people who made and used them. We are delighted to be a part of such an important and well-respected philanthropic event.”

The Winter Antiques Show benefits the East Side House Settlement, a social services agency for the low-income Mott Haven section of the South Bronx. Presenting more than seventy antiques specialists exhibiting American, English, Continental, and Asian objects, the show runs January 19 to 28.

The selection of Colonial Williamsburg artifacts, many from its DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, reflects the breadth of the foundation’s antiques holdings. Included are paintings, prints and maps, furniture, ceramics, metals, and tools from the late seventeenth century to the early twentieth. Though many are British or American, examples of French, German, and Chinese decorative objects are among the treasures.

Credit for them, and all of Colonial Williamsburg, is due first to the generosity of the late John D. Rockefeller Jr., the philanthropist who financed the city’s restoration. Second, but as important, it is owed to the hundreds of thousands of Americans since who have contributed antique art and furniture, as well as money and time, to the non-profit educational foundation Rockefeller created and endowed for Colonial Williamsburg’s stewardship.

As well as art, Colonial Williamsburg’s collections include eighty-eight eighteenth-century structures, greens, Colonial Revival gardens, and reconstructions of the Governor’s Palace, the Capitol, and the Raleigh Tavern. There are, moreover, scores of other structures modeled on buildings familiar to such men as Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, and Lawrence Washington’s grandson.

Seventy-five years ago, in the winter of 1926, Rockefeller and a clergyman, the Reverend Doctor W. A. R. Goodwin, bought the first house that would become part of the Colonial Williamsburg collections. The purchase helped launch their collaboration in a program to return Williamsburg to its eighteenth-century appearance and ambience.

Rockefeller had twice visited the city and explored it, the first time with his wife, Abby, and four of their five sons. Goodwin, rector of Williamsburg’s Bruton Parish Church and the town’s leading booster, was their tour guide. In their excursions, he became attached to their youngest boy, David, who went away with a clutch of postcards and a taste for the pecans that fell from a tree in Goodwin’s yard. Among the places the minister showed the family was a two-story brick home on the north side of the city’s central thoroughfare, the Duke of Gloucester Street.

Built as a townhouse in the 1750s for planter-politician Philip Ludwell III, it was a hip-roofed, five-bay early Georgian home laid up in Flemish bond with glazed headers. Ludwell’s second daughter, Lucy, the wife of John Paradise of London, inherited the place in the early nineteenth century. Known today as the Ludwell-Paradise House, the property had been on the market for about a year with no takers. The price was $8,000. On December 4, a likely buyer from Washington appeared. Goodwin wrote two letters to New York asking Rockefeller to buy it first. Rockefeller hoped to remain anonymous; Goodwin told him their agreement “would be known only to you and to myself.”

Rockefeller wired a reply that arrived at 11:28 a.m. December 7. It kept his identity safe from the telegraph office, but told Goodwin all that he needed to know. It read: “Authorize purchase of antique referred to in your long letter of December four at eight on basis outlined in shorter letter of same date. David’s Father.”

Colonial Williamsburg’s participation in the Winter Antiques Show is the first in a year-long series of events celebrating the seventy-fifth anniversary of that transaction, a year that will kick off the foundation’s first comprehensive fund-raising effort, the Campaign for Colonial Williamsburg. A multimillion dollar, multiyear drive to secure new support for the foundation’s people, places, and purposes, it aims to ensure always, in the words of Rockefeller’s motto, “That the future may learn from the past.”

Nothing quite so readily expresses the idea of time past and time to come than a timepiece, and one of Colonial Williamsburg’s grandest is displayed at the Winter Antiques Show—a mahogany tall clock made about 1745 by William Claggett. A Bostonian, Claggett moved to Newport, Rhode Island, where he made clocks and navigational instruments for the shipping merchants of the Atlantic trade. Nearby stands a mahogany chest-on-chest distinguished for its Georgian symmetry and crafted by Thomas Affleck for David Deschler of Philadelphia in 1775. Trained in Edinburgh and London, Affleck left in 1763 for Pennsylvania where he joined other British émigrés offering specialized craftsmanship to wealthy patrons in what was America’s largest city.

Other objets d’art, not so practical but no less striking, include High Life Below Stairs, an oil painting by John Collett of London. Collett’s 1763 scene gently lampoons a well-born woman whose servant is transforming her into a grande dame.

Colonial Williamsburg’s atmosphere and feeling mirror the social and material milieu captured in such eighteenth-century works. Throughout the show, everyday objects—from flatirons to birdcages—as well as illustrations of daily activities, offer insight on the lifestyles and culture of the day.

Then, for everyone who admires the exuberance and naïveté of unschooled artists, there are the items from the foundation’s Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum.

In 1935, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s first wife, chose the Ludwell-Paradise House to exhibit some of the folk art she collected. Much of it had been presented in 1932 at the Museum of Modern Art in the exhibit American Folk Art: The Art of the Common Man in America, 1750–1900. In 1939, she donated to Colonial Williamsburg many of the paintings, carvings, and folk art she had assembled. They stayed in the Ludwell-Paradise until 1955, seven years after her death, her husband provided the funds for construction of her namesake museum.

Among its items in the Winter Antiques Show is the Banjo Chair made in New Hampshire during the 1920s of birch, maple, ebony, and tulip poplar with electrical wire. The seat—its use was artistic, not utilitarian—bears the shape and decoration of a banjo with inlaid strings and tuning pegs.

Not to be overlooked are the archaeological discoveries on exhibit, fragments of the past recovered from the ground that assist in the study of eighteenth-century life. One is a pre-1785 soapstone tobacco pipe bowl, probably Cherokee, that may have been used during meetings between Virginia’s governor and the colony’s Indians. Retrieved from the Charlton Coffeehouse site on Williamsburg’s Nassau Street during an archaeological dig in 1999, the pipe suggests the diverse population of colonial Williamsburg.

A copy of Captain John Smith’s Map of Virginia is among the rare items presented. Printed on a London press in 1612 to illustrate one of Smith’s tracts on his Jamestown days, it is among the earliest English representations of the Chesapeake region. Based on the colonists’ explorations of the bay and its rivers in 1607 and 1608, the map reproduces early drawings of the region’s aboriginals, and was the prototype for charts of Virginia for the next fifty years.

Another uncommon item on display is a circa 1743 etching of a magnolia by Georg Dionysius Ehret, one of 220 plates in a two-volume set compiled by English naturalist Mark Catesby. The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, published in 1747, documented Catesby’s gathering of natural specimens from the colonies and is an important work on North American natural history.

The Winter Antiques Show’s 2001 loan exhibition “The Best Is Not Too Good For You:” Colonial Williamsburg Celebrates 75 Years of Collecting, is sponsored by the Chubb Group of Insurance Companies. It is curated by Colonial Williamsburg’s Philip Zea and designed by New York’s Stephen Saitas.

Sophia Hart, a manager in the Colonial Williamsburg public relations office, specializes in the foundation’s museums. For more information on them, their collections, and the Winter Antiques Show, visit the Colonial Williamsburg website at www.colonialwilliamsburg.org and the Winter Antiques Show website at www.winterantiquesshow.com.