Page content

Speaking of the Past: the Words of Colonial Williamsburg

by James Breig

Interpreter Mark Muller, portraying George Washington, addresses a crowd of Colonial Williamsburg visitors from a platform behind the Governor's Palace.

It's a clear Virginia day at Colonial Williamsburg. Behind the Governor's Palace, the eighteenth-century George Washington, in the person of a character interpreter, stands on a slightly raised platform, speaking to a twenty-first-century audience about the political tensions that led to the American Revolution. At the end, one among the crowd asks a question, an inquiry that shows the listener hasn't been paying attention. Good naturedly, the general says: "Did you tune me out when I talked about that just a few minutes ago?"

The visitor laughs, and the crowd laughs with him, and Washington laughs and answers the question, and the ever-so-slight linguistic hitch-if that's what it was-goes all but unnoticed. The scene, nevertheless, illustrates an ever-present challenge for the costumed men and women of Colonial Williamsburg, the interpreters who daily don not only the clothing but the vocabulary of the 1700s. Washington said "tune out," a phrase not coined until broadcasting began. Its entry in the Oxford English Dictionary says it first appeared in print in 1931. The real-life Father of Our Country, knowing nothing of twirling knobs and dials to get better radio reception, could not have used so anachronistic an expression. But on that day, in this setting, in these circumstances, those words of that jocular reproach were, perhaps, quite timely.

Seven days a week, Colonial Williamsburg visitors listen to a "person of the past" talk about politics, religion, business, family life, slavery, and more. These interpreters work at the art of speaking at once authentically and understandably. Training-through lectures, publications, and mentors-emphasizes the colonial terminology, but strives to balance the language of speakers from 250 years ago with the need to be comprehended by contemporary listeners in a museum experience.

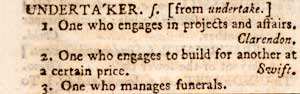

An entry in a 1750 dictionary, below, demonstrates the difference in some eighteenth-century definitions.

Like most live languages, English changes as it goes, collecting new words and phrases to fit new conditions and modifying or discarding ones that no longer work. It was as true three centuries ago as it is today. Richard W. Bailey, a University of Michigan professor writing a book on eighteenth-century English, says that three hundred word-forms came into the language between 1700 and 1720 alone. The list includes "anyhow," the use of "knuckle" as a verb, "professoress" for a female teacher, and "malaria," derived from Italian words meaning "bad air."

Thomas Jefferson, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, may have coined "belittle" and "electioneering;" his uses of them are the first references in the OED. Jefferson and Washington are both credited with making "progress" a verb, an Americanism ridiculed by Britons.

Some eighteenth-century words still used today now have different meanings. "Nice" meant "finicky" or "over-scrupulous" as the 1700s began, Bailey says, but it acquired its current meaning before that century ended. Such shifting meanings can confuse modern ears. For example, when Jefferson was asked to study plans for the new federal Capitol, he invited undertakers to advise him. It seems odd that Jefferson would require the aid of morticians to examine blueprints and measure archways, until one understands that eighteenth-century "undertakers" were people-in this instance, building contractors-who "undertook" projects.

Sorting through obscure words, obsolete words, and familiar words with unfamiliar meanings, are among the linguistic landmines through which Williamsburg's people of the past must pick their ways. Keeping them speaking properly in the present is the work of behind-the-scenes experts like historian Cathy Hellier. They provide interpreters with grammar workbooks and vocabulary lists. One hand-out, "Eight Easy Ways To Make Your Speech Sound More Eighteenth-Century," suggests that interpreters say, " 'tis" and " 'twill" in place of "it's" and "it'll." It also recommends "sir" and "madam" in direct address to provide an atmosphere of proper formality, even in everyday conversation.

"We want to help interpreters understand how sentences were constructed, what vocabulary was used, how the meaning of words has changed, and what we say now that we didn't say then," Hellier says. "Language is one clue for visitors, along with architecture and costumes, that they are in another culture."

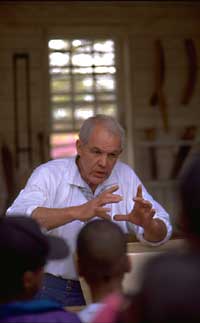

Interpreter Don Kline, left, confers with Mark Howell, acting director of program development, about the syntax found in an eighteenth-century book.

Mark Howell, acting director of the department of program development, says his office strives "to create a sense of the atmosphere of the eighteenth century." To that end, interpreters are instructed to use "above stairs" and "lustre" in place of "upstairs" and "chandelier." But, he says, "we don't want to draw attention to the language. It has to be judicious. If interpreters become too clever, they can be intimidating. Visitors won't talk to characters if they feel intimidated. They want to be 'back there' and have entry into the eighteenth century as escapist fare-but with integrity."

Hellier, who occasionally becomes a person of the past, says it is "easy for interpreters to get arcane because they are so knowledgeable. But that can leave visitors behind. If we use an unfamiliar word without immediately explaining it-through a parenthetical expression, for example-the visitors' wheels spin on that one word and everything else we say is lost. Our goal is to enlighten people."

Thus historic interpreters undergo training, some of which involves mentors. A new employee might serve a sort of apprenticeship as a butler's footman or lawyer's witness-largely silent roles that allow them to listen to experienced interpreters before setting off on their own. "Listening to others was very helpful," says Karen Schlicht, who portrays Ariana Randolph. She learned to use such words as "t'isn't" and "betwixt" as shorthand devices for establishing that she lives in another century. She also learned from lectures and from reading eighteenth-century material.

But those who walk about Williamsburg in long skirts or short pants have to do more than learn about the past; they have to undo the present by weeding out modernisms, which means anything that entered American English after 1800. Out go "okay" and "no problem." In place of "I'd like your input," interpreters are advised to substitute "What are your sentiments?" But some seemingly modern sayings have colonial roots, Hellier says, such as "Birds of a feather flock together," "When in Rome, do as the Romans do," and "No news is good news." Using aphorisms like those, she says, builds a bridge between interpreters and visitors because they "help people understand that what they say reaches into the past."

Historian Cathy Hellier, here demonstrating a difference between eighteenth-century and twenty-first century phrasing, coaches interpreters in colonial speechways.

Hearing a person of the past say, "How does your lady, sir?" some Raleigh Tavern or Capitol visitors might imagine that their predecessors spoke more elegantly and properly. But character interpreters are reminded to employ such ungrammatical constructions as "suprisingest" for "most surprising" and to mangle subject-predicate agreement. For example: "The fellow's pains and fever was very bad." Colonial people "didn't worry about tenses," Howell says. "Singulars and plurals were messed up. English is not a logical language in terms of its grammar."

Proper usage and spelling have never been settled issues. In the 1790s, assessing her husband's election chances, Abigail Adams penned a letter to her John in which she made three stabs at spelling a word before giving up: "New York will be the balance in the scaile, skaill, scaill (is it right now? it does not look so)." One cause of Adams's bafflement is that dictionaries were a relatively new phenomenon.

In 1440, a Dominican monk in England compiled the Promptorium parvulorum sive clericorum or Storehouse for Children or Clerics, which provided Latin equivalents for 10,000 English words. In 1538, Sir Thomas Elyot gathered the Bibliotheca, also an English-Latin dictionary. It wasn't until 1604 that Robert Cawdrey produced:

A Table Alphabeticall, conteyning and teaching the true writing, and vnderstanding of hard vsuall English wordes, borrowed from the Hebrew, Greeke, Latine, or French. &c.

With the interpretation thereof by plaine English words, gathered for the benefit & helpe of Ladies, Gentlewomen, or any other vnskilfull persons.

Whereby they may the more easilie and better vnderstand many hard English wordes, which they shall heare or read in Scriptures, Sermons, or elswhere, and also be made able to vse the same aptly themselues.

Legere, et non intelligere, neglegere est. As good not read, as not to vnderstand.

It was the first dictionary giving definitions in English of English words. Cawdrey promised readers he would provide "plaine . . . words" for hard ones, a useful tool for those who spoke publicly "before the ignorant people." Such orators, he said, especially preachers, should "never affect any strange . . . termes, but labour to speake so as is commonly received, and so as the most ignorant may well understand them."

He defined about 2,500 words, from "ABandon-cast away, or yeelde vp, to leaue or forsake," to "ZOdiack-a circle in the heauen, wherein be placed the 12. signes, and in which the Sunne is mooued." To him, "accident" meant "a chance, or happening," and "conferre" was "talke together." In his view, "enormious" was equal to "out of square," and "Iudaisme" meant "worshipping one God without Christ."

The first English dictionary to call itself one was Henry Cockeram's The English Dictionarie, published in 1623. In 1702's A New English Dictionary, John Kersey diverged from his predecessors; they had defined only difficult words, he incorporated everyday terms. Kersey directed his book especially to "young scholars, tradesmen, artificers, and the female sex, who would learn to spell truely." Then came the Universal Etymological English Dictionary in 1721, the work of Nathan Bailey. Like the Oxford English Dictionary that would arrive a century-and-a-half later, Bailey included literary quotations to show the contexts in which words were used.

Interpreter David Tarleton, portraying a member of revolutionary Virginia's Committee of Safety, fills the ears of an audience of Courthouse visitors with some well-chosen eighteenth-century words on the perfidy of Lord Dunmore.

Cawdrey and Bailey are obscure pioneers in lexicography, they and their confreres having been outshined by Samuel Johnson, whose two-volume A Dictionary of the English Language, which came from the press in 1755, was the final word about words for a century. Johnson said his effort was "doomed only to remove rubbish and clear obstructions from the paths, through which Learning and Genius press forward to conquest and glory, without bestowing a smile on the humble drudge that facilitates their progress." It took him nine years to finish his massive work. When he dispatched the final pages to be typeset, the printer said, "Thank God, I have done with him."

Those are some of the reference works to which colonists could turn for guidance. They did not get an American handbook until 1783 when Noah Webster released A New and Accurate Standard of Pronunciation.

Such resources as Johnson's dictionary, Hellier says, proliferated because in the Age of Reason people had an urge to apply order in every aspect of their lives, including music, architecture, and language. In 1712, Jonathan Swift, who longed for "some method [of] fixing our language for ever," published A Proposal for Correcting, Improving, and Ascertaining the English Tongue. He said that "from the Civil War to this present Time, I am apt to doubt whether the Corruptions in our Language have not at least equalled the Refinements in it; and these Corruptions very few of the best Authors in our Age have wholly escaped. . . . That Licentiousness which entered with the Restoration . . . fell to corrupt our Language."

George Campbell, author of The Philosophy of Rhetoric in 1776, was aghast at the degradation of English by such slang as "the abbreviation of polysyllables, by lopping off all the syllables except for the first, or the first and second. Instances of this are hyp for hypochondriac, rep for reputation, ult for ultimate, incog for incognito, hyper for hypercritic, extra for extraordinary."

If the British wanted to hear their language used properly, they might have gone to Virginia, according to a writer of the day. About 1720, College of William and Mary Professor Hugh Jones returned to England from Virginia and wrote that "the Planters and even the native Negroes generally talk good English without Idiom or Tone, and can discourse handsomely on most common subjects."

Different scholars took different approaches to codifying English. Some wanted an academy, as France had, to set down rules and guard the language. Daniel Defoe thought such an institution could "polish and refine the English Tongue, and advance the so much neglected Faculty of Correct Language" while establishing "Purity and Propriety of Stile." But Joseph Priestly, the scientist, preferred a looser approach, saying that "the custom of speaking" should be "the original and only just standard of any language."

The middle ground seemed to be grammar books in which linguists and teachers attempted regulations-at least for their time. This effort included contributions from women; Ann Fisher established the now-vanquished rule that "he" could mean "he or she" when used generically.

One of the most influential of these books was Robert Lowth's A Short Introduction to English Grammar. A professor of poetry at Oxford who would become an Anglican bishop, Lowth applied his expertise in Latin grammar to English, creating many of the rules-when to use "who" and "whom," for example.

"They were trying to impose order on English," Hellier says. "More and more people were writing grammar books with 'shoulds' and rights and wrongs. Before then, English had sort of developed on its own. In the eighteenth century, people wanted rules. They could afford education for their children and wanted them to speak properly. Also, people could move up in society, and wanted to speak in the correct way." For that, people thought, the guidance of grammarians was useful.

Wheelwright Ron Vineyard, like most Colonial Williamsburg tradespeople, relies on modern speech forms laced with antique terms to explain the fine points of colonial crafts.

More than two centuries later, grammars and dictionaries of the time provide researchers with eighteenth-century language insights. But they are not the only-and often not the preferred-resources for interpreters. Letters, diaries, trade ads, port records, and public documents hint at how English was spoken.

Dialogue among characters in eighteenth-century novels offers glimpses of how men and women, and members of the social strata talked. At Virginia's Gunston Hall, the restored home of George Mason, interpreters learn by reading such material as the novel Pamela by Samuel Richardson, the journals of Philip Fithian and William Byrd, Defoe's Diary of the Plague Year, and letters exchanged by Jefferson and Adams. Laurie L. Kittle, coordinator of the Gunstonians, the living history players of Gunston Plantation, also turns to the Bible, Mason's letters, and issues of the Pennsylvania Gazette, an eighteenth-century newspaper available on the Internet at www.accessible.com/, like is Cawdrey's A Table Alphabeticall, at prod.library.utoronto.ca/utel/ret/cawdrey/cawdrey0.html. She likes to salt the scenarios she writes with words and phrases that propel visitors through time: "Providence" for "God," "gut-foundered" for "hungry" and "antique virgin" for "old maid."

At Colonial Williamsburg, Hellier has combed the same sorts of sources, preferring letters that are colloquial and approaching plays cautiously because dramatic conventions can lead researchers down the wrong paths. She finds particular value in Evelina, a novel by Frances Burney who kept journals in which she recorded conversations among visitors to her home. Hellier also treasures guides for English-speaking people who were learning foreign languages since the instruction, just like its modern equivalents, offers examples of vernacular English. From this material, she can deduce "how people addressed each other, what vocabulary was in use, how sentences were structured."

Rural tradesman Wayne Randolph and his colleagues take an informal approach to conversations with Colonial Williamsburg visitors who pause to chat about colonial agriculture and the like.

She also has found Virginia regionalisms that might have puzzled Bostonians and Philadelphians of the period, like the use of "backwoods" for "frontier." Fithian, a New Jersey tutor who frequented Williamsburg, was puzzled by the word "sale" until he found out that it meant "vendue," a Jerseyism.

Despite the information research has uncovered-what Hellier terms "a huge corpus of data"-much remains to be done. The realm of inflection and accents is almost unexplored and may remain so. Without recordings, scholars cannot definitively determine how words were pronounced.

Ideas about how African-Americans spoke are being reexamined. "The field of African-American linguistics is reinventing itself," Hellier says. "Experts are questioning old assumptions and finding new resources. New things are coming out all the time."

A visitor to Colonial Williamsburg in the first part of the twenty-first century who snaps a photo of a character interpreter may not realize it, but that picture really is worth a thousand words. They are the words learned from training tapes and lectures, and taught by mentors and historians, all of them lending an aura of oral and aural authenticity when a person of the past bows and says, "Your humble servant, sir. 'Tis a fine, warm day."

James Breig, an Albany, New York writer and editor, contributed an article on the orrery to the winter 2000 journal.

| WAS IT SAID IN OLD WILLIAMSBURG? | |

|

Quiz yourself on the vocabulary of the eighteenth century. Decide which of the italicized words could have been used in 1700s Williamsburg: The magistrate should cop that runaway. Hand me my dumbbells. He is drinking moonshine. Don't use slang. The governor is a bigwig. The William and Mary campus needs attention. |

That subject is taboo. Indian summer is upon us. A sailor with a tattoo drank beside me at Wetherburn's

Tavern. The Randolphs are having a barbecue.

With the exception of barbecue we cannot certainly know if those ten words were spoken in eighteenth-century Williamsburg, but all could have because they entered English in the colonial era. By the way, the word "quiz" was in use in the eighteenth century, but it did not mean a small test until the middle of the nineteenth century. For about a hundred years before that, the noun "quiz" meant an odd person or thing. Its verb form meant "to make fun of." -James Breig |