Page content

Captain John Smith

by Dennis Montgomery

"An Ambityous unworthy and vayneglorious fellowe"

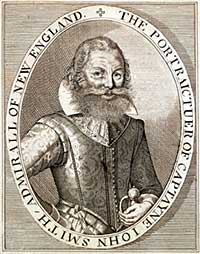

Captain John Smith is memorialized in this 1616 Simon van de Passe engraving.

In 1609 Captain John Smith dispatched a party of English under Captain Francis West from Jamestown—labeled “Iames-towne” on this map—upriver to the Falls or “The Fales.”

This 1616 engraving of Pocahontas by Simon van de Passe was made when she was 21.

HALFWAY THROUGH the voyage, somewhere in the Canaries, the Jamestown fleet's leaders clapped Captain John Smith into custody and accused him of concealing an intended mutiny. At the next stop, across the Atlantic in the Caribbean, they offered to hang him and got as far as hammering together the gallows. Before his fellow settlers threw him out of Virginia 32 months later, they would again propose to stretch Smith's neck, to banish him, and even to murder him.

That is not the Captain John Smith story familiar to the history buff. Even some academic historians prefer to remember the positive elements of the now popular captain's career. With some justification.

In his 51 years Smith was a compiler and writer of exuberant travelers' tales, an explorer, a mapmaker, a geographer, an ethnographer, a soldier, a governor, a trader, a sailor, an admiral, and the editor of a seaman's handbook.

Enormously energetic, his adventures and travels touch Europe, Africa, and America, and match the boldest exploits of fearless knighterrantry. In this hemisphere alone, he was an early explorer not only of the Chesapeake but of New England's coast and, at home in England, an enthusiast in the cause of America's colonization.

By his admirers, Smith is credited with almost singlehandedly preserving the first English Virginians from the ravages of their own sloth as well as from the hostility of their native neighbors. Except for his pen, chapters of America's earliest history would to us be lost; for much of the story of Jamestown comes from the captain. As an assembler of other men's accounts and a writer of his own, Smith is responsible for five swashbuckling early 17th-century descriptions of the colony and its struggles, one richly illustrated. He produced seven other volumes and helped bring to the press a still stunning Virginia map.

Examining Smith's productions, it is difficult to conclude he is due less than a full measure of credit in the founding of the nation. Like many writers of the day, he was not an author to stint on praise of himself, the praise for which his fame is enshrined, once in awhile in bronze. Yet every story has more than one side, and Smith was a many-sided man.

It was June, two months after landfall in Virginia and more than four months after his arrest at sea, that the settlement's government got around to excusing Smith from custody. He took the liberty to join, some say engineer, a coup against President Edward Maria Wingfield in September.

By January, near his 28th birthday, Smith was condemned again to the noose, and only the last minute arrival of a supply vessel this time saved his neck. That was just after Pocahontas, 13, is said to have delivered him from a squad of Indian executioners.

Smith ousted another president in July and got himself elevated to that office in September. His enemies, eventually a majority of the settlers, suspected him of aiming to make himself a tyrant king. Smith denied the allegation; yet, by the end of his Jamestown sojourn, he did indeed reign alone, terrorizing Indians, bullying Englishmen, and flogging whoever happened to cross him. He once went so far as to command the assassination of a squad of turncoat colonists--by poison according to one account, by shooting and stabbing according to his own.

Before he had done, the aboriginals sorely wanted to brain him, some of his countrymen compounded to bar him from the settlement, and, penultimately, others conspired to shoot him in his sleep. In the end, the English resolved on sending Smith home to answer for, among other things, inciting Indians to attack them.

Dispatched on the same voyage were eight or nine witnesses against him and a letter that said in part: "This man is sent home to answer some misdemeanors whereof I persuade [myself] he can scarcely clear himself from great imputation of blame."

George Percy, who succeeded him as chief executive, wrote that this man Smith was "an Ambityous unworthy and vayneglorious fellowe."

Like the yeomanclass Smith, gentleman George Percy was an original Jamestown settler and a participant in its inaugural disasters. A witness to Smith's transactions, Percy is another primary source of the Old Dominion's oldest episodes. After Smith's self-aggrandizing books began to gain circulation, Percy took exception for the record. He wrote, "that many untruths concerning These proceedings have been formerly published wherein The Author hath not Spared to Appropriate many deserts to himself which he never Performed and stuffed his Relations with so many falsities and malicious detractions . . ."

Typically quoted by historians on the point of Smith's veracity is Thomas Fuller, author of a biographical dictionary called The Worthies of England. Publishing in 1661, only 30 years after Smith's death and while the memory of the captain was fresh, Fuller said that such were Smith's "perils, preservations, dangers, deliverances, they seem to me almost beyond belief, to some beyond truth. Yet we have two witnesses to attest them, the prose and the pictures, both in his own book; and it soundeth much to the diminution of his deeds, that he alone is the herald to publish and proclaim them."

In fact, Smith was not the only one to publish and proclaim them. In 1631, the year Smith died, the London press issued a satirical poem, The Legend of Captain Iones, by the Welsh clergyman David Lloyd. A bawdy, ridiculing parody of Captain Smith's autobiography, the poem's popularity sustained a half dozen editions during the next 40 years.

To quote a snatch of the epic:

. . . Tis known

Iones fancies no additions but his own;

Nor need we stir our brains for glorious stuff

To paint his praise, himself hath done enough.

In the 20th century, historian Alden T. Vaughan wrote that the poem shows "Fuller's doubts about Smith must have been widely shared in the seventeenth century and . . . many of his contemporaries may have seen Smith more as a braggart, even buffoon, than as hero." More charitable, historian Samuel Eliot Morison concluded that Smith was "a liar if you will; but a thoroughly cheerful and generally harmless liar."

The Complete Works of Captain John Smith fill three volumes. Published for the Institute of Early American History and Culture, they were edited by the late Philip L. Barbour, the foremost modern Smith scholar. The best place to follow Smith's adventures is in those pages, but some of the more remarkable episodes are worth spotlighting here.

Smith reported he was imprisoned on the voyage to Virginia about February 21, 1606/07, just after the fleet stopped for water, wood, and food, because he was "suspected for a supposed Mutiny, though never so much matter." Barbour believed there may have been a dispute there over how to go about the gathering.

The fleet stopped again for supply at the Caribbean island of Nevis on March 28, 1607. Smith wrote in his 1630 The Tre Travels, Adventures, and Observations of Captaine John Smith: "Such factions here we had, as commonly attend such voyages, that a pair of gallows was made, but Captain Smith, for whom they were intended, could not be persuaded to use them."

A version of these events he published in 1612 is more illuminating. He had been:

restrained as a prisoner upon the scandalous suggestions of some of the chief [people] (envying his repute) who fained he intended to usurp the government, murder the council and make himself king, that his confederates were dispersed in all the three ships, and that diverse of his confederates that revealed it, would affirm it, for this he was committed as a prisoner: 13 weeks he remained thus suspected. . . .

Once in Virginia, the colony's chief people wanted to ship him home for punishment straight-away, but Smith says he defended himself so fearlessly that he was allowed to remain. His account speaks for itself:

he much scorned their charity, and publicly defied the uttermost of their cruelty. He wisely prevented their policies, though he could not suppress their envies, yet so well he demeaned himself in this business, as all the company did see his innocency, and his adversaries' malice, and those suborned to accuse him, accused his accusers of subornation; many untruths were alleged against him; but being so apparently disproved begat a general hatred in the hearts of the company against such unjust commanders; many were the mischiefs that daily sprung from their ignorant (yet ambitious) spirits; but the good doctrine and exhortation of our preacher Master Hunt reconciled them, and caused Captain Smith to be admitted of the Council,

which helped the president run the colony, on June 10.

Smith, at least as he recounts it, often was unjustly accused of something or other. One of the earliest accusers was President Wingfield, Jamestown's president until September 10. That day settler Gabriel Archer presented Wingfield with a list of grievances and informed him that he was ousted and would stand trial. Captain John Martin backed Archer up, but Wingfield believed Smith was the first and only person to collect the charges against him. "Master Smith's quarrel" with him, Wingfield said, was "because his name was used in the intended and confessed mutiny. . . ."

Now John Ratcliffe became president. But Smith became powerful, signing on as Ratcliffe's chief agent, the man to take order of the work and, more importantly, the recruitment of food among the Indians. From that moment, Smith's grip on Jamestown closed. In a settlement invariably on the verge of starvation, control of the food supply could be control of everything.

If this was an unhappy development for the colonists, the Indians would regret it, too. On his very first call on a tribe for supplies, Smith attacked. He says the Kecoughtans, who lived near modern Hampton, scorned him and derided his offers to barter. So "seeing by trade and courtesy there was nothing to be had, he made bold to try such conclusions as necessity enforced, though contrary to his Commission: Let fly his muskets, ran his boat on shore, whereat they all fled into the woods." The Kecoughtans counterattacked, the English picked off a couple, the Indians sued for peace, and Smith sailed off with a boatload of corn.

Though not all of his trading encounters led to bloodshed, the first one made plain the possibilities of refusing to bargain. Promises of violence were frequent, and though the orders from England were not to annoy the natives, Smith ignored them as he judged circumstances to require.

It was a mission of trading and exploration along the Chickahominy River, just west of Jamestown, that gave rise to the Pocahontas legend. Smith made his way first in a barge and then in a canoe, scattering his company in his wake. Indian women lured two indiscreet soldiers asore from the barge to their deaths in an ambush. Braves killed a third who guarded the canoe. Among the men killed were two called Robinson and Emery.

Smith walked inland into the arms of a Pamunkey hunting party. Marched roundabout to Powhatan, the "emperor" of the Tidewater tribes, Smith was promised his freedom in four days. As he told it in his Generall Historie, however, he was the next day summoned to Powhatan's house. Smith's account:

At his entrance before the King, all the people gave a great shout. . . . [A] long consultation was held, but the conclusion was, two great stones were brought before Powhatan: then as many as could laid hands on him, dragged him to them, and thereon laid his head, and being ready with their clubs, to beat out his brains, Pocahontas the King's dearest daughter, when no entreaty would prevail, got his head in her arms, and laid her own upon his to save him from death.

Powhatan decided he would instead regard Smith as a son, make him a tributary werowance--as headmen were called--and bestow on him a territory just downriver. Smith left for Jamestown two days later, the previously promised fourth day, skirting the site of what would be Williamsburg.

The last 27 words of the passage quoted is the sum and substance of the Pocahontas story, repeated for 400 years and carved in stone in a frieze in the rotunda of the nation's Capitol. So far as the record shows, however, it is a story to which Smith forbore publicly even to allude until 1622--15 years after the fact--and not to disclose even in its scanty detail until 1624. In the interim he had published three other volumes of his Virginia experiences and one of other New World adventures.

By the time Smith shared the story with the printer, Pocahontas had been to England, where she died in 1617 after becoming famous. Powhatan, the other principal, was gone, too, and there was no one alive to contradict the captain.

Curiously, Smith's first book, A True Relation, published in 1608 less than a year after Smith's capture, describes in another context the same mode of execution he would eventually report he had escaped. Moreover, in the intervening years, a Spanish work with a strikingly similar Indian-princess-rescues-white-man-from-cruel-father's-execution tale appeared in London. And some historians see a Pocahontas parallel in the Miranda-Ferdinand episode from Shakespeare's The Tempest. That play, in turn, seems to have been inspired by the story of the wreck in Bermuda of a hurricane-tossed, Virginia-bound ship during Smith's Jamestown presidency.

Some 19th-century American scholars remarked on the delay in publication of the tale, noted discrepancies among Smith's various capture accounts, and questioned the authenticity of the Pocahontas rescue. Albert Bushnell Hart concluded Smith was one of the "great American historical liars," and essayist Henry Adams said, "It is perfectly clear that the statements of the Generall Historie, if proved to be untrue, are falsehoods of rare effrontery."

Proving them to be untrue is, of course, impossible. So, after so great a passage of time, is proving them authentic.

Barbour believes Smith misunderstood what had happened to him. It could be, he says, that Smith experienced an Indian naturalization or adoption rite in which he was symbolically killed, saved, and reborn with a status comparable to one of Powhatan's natural sons. Thus an obstreperously ungovernable Englishman would be transformed into a deferentially manageable subchief.

As uncertain as we are about the Pocahontas legend now, it was certain at the time that men in Smith's care had been lost on the expedition, and that President Ratcliffe and the Council saw that as an opportunity to be rid of him. Smith's account goes:

Some no better than they should be, had plotted with the President, th next day to have put him to death . . . For the lives of Robinson and Emery, pretending the fault was his that led them to their ends, but he quickly took such order with such Lawyers, that he laid them by the heels till he sent some of them prisoners for England.

What happened, actually, was that Christopher Newport sailed up in the nick of time with new colonists and fresh supplies and arranged Smith's release. When Newport returned to England, Smith's friends-turned-foes Martin and Archer went with the ships, eventually to return and to get even.

The score settling would wait until August of 1609; Smith would have 20 months of respite from what he described as their malice. By June, however, he was persuaded other comrades were conspiring to do him in. On a trading trip to the Potomac--a river he seems to have explored at least to the falls at modern Washington--he got into one of his scrapes with the Indians. After the dust settled, he said, "We were kindly used of those Savages of whom we understood, they were commanded to betray us, by the direction of Powhatan, and he so directed from the discontents at Jamestown, because our Captain did cause them to stay in their country against their wills."

In other words, Smith believed the Indians who ambushed him 100 miles from Jamestown had been put up to it by Powhatan to gratify and be rid of settlers who blamed Smith for being stuck in Virginia. If it is improbable, it may not have been impossible. It was what came into Smith's mind, and it was not the last time Smith would accuse subordinates of trying to undo him.

EVENTUALLY, the prophecies would fulfill themselves. In a hint of what was to come, colonists tried to keep him out of Jamestown, to leave him to his fate in the forest, when he returned from a November bartering expedition. Smith said they were jealous.

That summer he had authorized the ouster of his old friend President Ratcliffe and helped install his new friend Mathew Scrivener. Scrivener lasted a little more than a month; the Council elected Smith president September 10, his term to run a year. By January, all other members of the Council had died, several in supposed pursuit of yet another plot against the captain, and Smith was in sole and complete command.

This was the winter of the no work, no eat order. Smith says he delivered it to the starving settlers in these words:

Countrymen, the long experience of our late miseries, I hope is sufficient to persuade every one to a present correction of himself, and think not that either my pains, nor the [investors'] purses, will ever maintain you in idleness and sloth. I speak not this to you all, for diverse of you I know deserve both honor and reward, better than is yet here to be had: but the greater part must be more industrious, or starve, how ever you have been heretofore tolerated by the authorities of the Council, from that I have often commanded you. You see now that power rests wholly in myself: you must obey this now for a Law, that he that will not work shall not eat (except by sickness he be disabled) for the labors of thirty or forty honest and industrious men shall not be consumed to maintain an hundred and fifty idle loiterers. And though you presume the authority here is but a shadow, and that I dare not touch the lives of any but my own must answer it: the Letters patents shall each week be read to you, whose Contents will tell you the contrary. I would wish you therefore without contempt seek to observe these orders set down, for there are now no more Councilors to protect you, nor curb my endeavors. Therefore he that offends, let him assuredly expect his due punishment.

Among the individuals to whom Smith thought punishment was due were a group of renegade German colonists--Dutchmen, he called them--encamped with Powhatan. Smith had sent them off to amuse the emperor, and they had elected to stay. That was, after all, where the food was. With the help of confederates inside the fort, they were also stealing weapons and tools, and proposed to lead an attack on Jamestown. Smith understandably called them traitors and ordered them assassinated. The idea was to poison them, or have them shot or stabbed, depending on who you believe. No matter, the runagates seem not to have come within Smith's reach; others did.

Every few months, it seems, a group of colonists would discuss hijacking Jamestown's pinnace and sailing for the English fishing fleets at Newfoundland. Smith credited himself with stopping each of these projects. "But if I find any more runners for Newfoundland with the Pinnace, let him assuredly look to arrive at the Gallows." He also made this an occasion to reinforce his strictures on work, declaring, "he that gathers not every day as much as I do, the next day shall be set beyond the river, and banished from the Fort as a drone, till he amend his conditions or starve."

Lesser infractions he punished at the pillory or with shackles.

Examples of Smith's hard usage of the Indians range from the petty to the perverse. Some he browbeat; others he imprisoned, psychologically tormented, kept in chains, or forced to labor. Once he personally administered 20 lashes with a rope, and the occasional village was sacked or burned. Smith said such measures were required to keep the Indians at bay and amenable to furnishing supplies. Historian J. Frederick Fausz has termed it terrorism.

Word of what was happening reached England at the end of October with a vessel fresh back from Virginia. The troubles of the Jamestown crew were publicly blamed on the "misgovernment of the Commanders . . . dissention and ambition among themselves, and upon the Idleness and bestial sloth, of the common sort, who were active in nothing but adhering to factions and parts, even to their own ruin . . ."

Before this intelligence reached home, however, the colony's owners had redesigned Jamestown's administration, obtained a new charter, and dispatched a fleet of new settlers, the largest to date. Caught in a hurricane, the fleet arrived in pieces; but word of the new order of things got through. Smith was reproved and a replacement sent, though the captain was to be allowed a post as an Indian fighter.

By rights, Smith's presidency was terminated, and even Smith must have known it. But the papers to prove it were missing with the shipwrecked vessel on which they had been dispatched and, standing on ceremony, Smith declined to surrender power until his term expired September 10. Nor would he establish a new Council with which to share power in the meantime. The newcomers settled for electing gentleman Francis West as a sort of president-in-waiting, and Smith moved to patch things up with his disappointed subjects. He also shored up his power by ingratiating himself with the fleet's sailors.

According to Percy:

Captain Smith fearing the worst and that the seamen and that faction might grow too strong and be a means to depose him of his government so Joggled with them by way of feastings Expense of much powder and other unnecessary Triumphs That much was Spent to no other purpose but to Insinuate with his Reconciled enemies and for his own vainglory for the which we all after suffered. And that which was intolerable did give leave unto the Seamen to carry away what victuals and other necessaries they would.

The settlers had arrived too late in the year to plant food for themselves, and Smith, though he had known since July they were coming, was in no position to provide for them all, either out of the colony's stores, nature's bounty, or the Indian trade. Rations were short, growing shorter, and all agreed on the need to disperse. The example of the Indians and experience had taught Smith to spread colonists out with winter's approach, so that they need not all depend on the resources of a single area. West loaded a ship with munitions, food, and supplies, took 120 men to the falls of the James, the site of modern Richmond, and set them to building a fort near the river's edge. On a hill nearby was an Indian village commanded by a werowance the English called Little Powhatan.

West's settlers somehow got it into their heads that the river was the way to the South Sea, as the Pacific was called, and probably to the long-dreamed of gold fields Virginia was thought to contain. They apparently decided a fort hard by the stream would command the route to riches and make them wealthy gatekeepers. The Indians objected and killed men who strayed from the compound.

At month's end Smith, who figured the Pacific lay beyond the Potomac, took five soldiers up the James to check on matters, met West coming down, and arrived at the falls to declare the ground of West's Fort too flood prone. He was probably right, but he was little credited.

Henry Spelman, a perhaps confused young man who had only just arrived, was in Smith's party and years later wrote an account of what he thought happened next:

I was carried by Capt[ain] Smith our President to the Falls, to the little Powhatan where unknown to me he sold me to him for a town called Powhatan and leaving me with him the little Powhatan, He made known to Capt[ain] West how he had bought a town for them to dwell in desiring that captain West would come and settle himself there (but captain West having bestowed cost to begin a town in another place (misliked it: and unkindness thereupon arising between them) Capt[ain] Smith at that time replied little but afterwards conspired with the Powhatan to kill Capt[ain] West, which Plot took but small effect, for in the meantime Capt[ain] Smith was Apprehended and sent aboard for England.

Smith gave this explanation: He bought Little Powhatan's village all right, but Spelman was merely being apprenticed as an interpreter and was not part of the bargain. West's men spurned the deal, refused to budge, and denied Smith's authority. With his five men, Smith overawed all 120 and collared "all the Chieftains of those mutinies."

West's men, however, rallied, and drove Smith off. Falling back, Smith came to their ship, compounded with his latest friends the sailors, and took command of the vessel. Deprived of their ship and its stores, West's hungry men raided the Indian gardens on the hill, stole corn, beat and took Indians prisoner, and broke their houses. The Indians came to Smith to complain.

Percy said that: "Capt[ain] Smith Perceiving both his authority and Person neglected incensed and Animated the Savages against Capt[ain] West and his company Reporting unto them that our men had no more powder left them then would serve for one volley of shot."

By Smith's account the Indians told him that, for love of him, they had endured the newcomers' hostile treatment but:

they desired pardon if hereafter they defended themselves; since he would not correct them, as they long expected he would. So much they opportuned him to punish their misdemeanors, as they offered (if he would lead them) to fight for him against them. But having spent nine days in seeking to reclaim them; showing them how much they did abuse themselves with those great gilded hopes of the South Sea Mines, commodities, or victories, they so madly conceived, he set sail for Jamestown.

According to the captain, he had gone not half a league before his ship ran aground, and he could hear the attack in the distance. He was within easy reach of West's Fort when its men decided to submit themselves to Smith's mercy. They seemed to think he had some sort of sway over the Indian enemy.

Smith arrested six or seven of West's men, put the rest in the hill village, named the place Nonsuch, and made good the losses on either side, including the munitions and food he had captured and taken away himself. As Smith prepared to depart, however, Captain West reappeared, took command, and moved his men back to West's Fort by the river. Smith, by his account, threw up his hands and left for Jamestown by river.

Asleep in the boat, Smith said, he was terrifically burned when a spark fell from a match and touched off a gunpowder bag he wore at his waist. He jumped into the river to douse the flames and was recovered half drowned.

In those days a match was a pyrotechnic cord used to discharge a firelock musket or pistol. The practice was to light it and keep it burning when there was prospect of the need of force. Smith offered no explanation of why anyone attending him would be on the point of firing a weapon.

The pain of the burn, Smith said, was excruciating. More misery awaited him in Jamestown at the hands of Archer, Ratcliffe, and Martin. Smith said:

their guilty consciences, fearing a just reward for their deserts, seeing the President unable to stand, and near bereft of his senses by reason of his torment, they had plotted to have murdered him in his bed. But his heart did fail him that should have given fire to that merciless Pistol. So not finding that course to be the best, they joined together to usurp the government, thereby to escape their punishment.

Smith says he decided to go home for treatment of his burn. But he never surrendered his now-expired commission, only let it be stolen before he had "taken order to be free from the danger of their malice."

WHATEVER SMITH had decided for himself, his opponents had plans for him too. Percy, who also suffered from a burn and was heading home for treatment, was summoned from his ship to be made president in Smith's place. West would be returning to England.

Ratcliffe, Archer, and Martin delayed Smith's departure three weeks while they prepared charges and recruited witnesses. What the point was isn't clear; until 1612 the Virginia Company of London had no authority to correct in England persons accused of crimes in Virginia. No copy of the charges seems to have survived nor any record of a trial.

Nevertheless, Smith looked to his defense by publishing in his The Proceedings of the English Colony in Virginia of 1612 the testimony of two supporters, Richard Pots and William Phettiplace. From their relation, an outline of the indictment emerges:

Now all those men Smith had either whipped, punished, or any way disgraced, had free power and liberty to say or swear any thing, and from a whole armful of their examinations this was concluded.

The mutineers at the Falls, complained he caused the Savages assault them, for that he would not revenge their loss. . . . and this they proved by the oath of one he had oft whipped for perjury and pilfering. The dutchmen that he had appointed to be stabbed for their treacheries, swore he sent to poison them with ratsbane. The prudent Council, that he would not submit himself to their stolen authority . . . Others complained he would not let them rest in the fort (to starve) but forced them to the oyster banks, to live or starve, as he lived himself . . . Some prophetical spirit calculated he had the Savages in such subjection, he would have made himself a king, by marrying Pocahontas, Powhatan's daughter . . . Some that knew not anything to say, the Council instructed, and advised what to swear. So diligent they were in this business, that what any could remember, he had ever done, or said in mirth, or passion, by some circumstantial oath, it was applied to their fittest use, yet not past 8 or 9 could say much and that nothing but circumstances, which all men did know was most false and untrue. Many got their passes by promising in England to say much against him. I have presumed to say this much in his behalf for that I never heard such foul slanders, so certainly believed, and urged for truths y many a hundred, that do still not spare to spread them, say them and swear them, that I think do scarce know him, though they meet him, nor have they either cause or reason, but their wills, or zeal to rumor or opinion.

And so Smith left Virginia, never to return; a man scorned, and a prisoner, just as he arrived.

Colonial Williamsburg Journal Vol. 16, No. 3 (Spring 1994) p. 14.

Suggestions for further reading: