Page content

Online Extras

Seeds of Civil War

Library of Congress

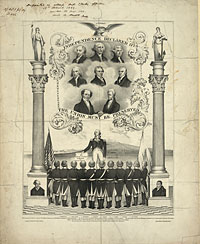

From around 1840, a tribute to the Revolution and the Declaration of Independence, with the first eight presidents and George Washington facing a file of soldiers representing the colonies. But in its beginnings, the union harbored the seeds of destruction.

Left to right, at the signing of the Constitution, Todd Norris as George Clymer, Chris Hall as George Mason, Tom Hay, Mark Schneider as James Madison, Ben Knecht, Ron Carnegie as George Washington, and Michael Rehm as Luther Martin.

Library of Congress

A Currier & Ives engraving of Fort Sumter under bombardment in 1861, the attack that began the Civil War.

Library of Congress

General Ulysses S. Grant led Union soldiers against fortified Confederate troops at Cold Harbor, Virginia, late spring 1864.

Library of Congress

African Americans collect bones from some of the 10,000–16,000 soldiers killed at the Battle of Cold Harbor.

How the Founders Sowed the Seeds of Civil War

by W. Barksdale Maynard

Whether America’s founders could have sown seeds of a more perfect union without dooming a following generation to reap the whirlwind of civil war is a question yet on the minds of the nation’s historians. Could anything have been done to avoid the bloodbath that took the lives of 2 percent of America’s population? It’s a staggering figure: 2 percent in today’s terms would mean the deaths of everybody in Connecticut, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. We usually think of nineteenth-century events—the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the Dred Scott decision—when we consider what precipitated the crisis. But the roots of the conflict go back further, back to the formative years of the United States.

The flowers of death and destruction germinated from slavery, unmistakably the chief cause of the Civil War—although economics, geography, culture, fear, and the constitutional ambiguities of states’ rights must be factored in. American slavery was a hybrid of seventeenth-century English mercantilism, colonial labor shortages, and what we call racism. It was an evil which, in the interests of revolutionary unity, the Second Continental Congress declined to eradicate in the Declaration of Independence, and which the Articles of Confederation left to blight the Constitution.

Slavery’s taproot was the three-fifths clause, cultivated in the steamy Philadelphia summer of 1787, as a nation struggled to be born. After weeks of debate, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention faced an impasse, and it seemed the fragile project of national reorganization might collapse. Then, on July 16, they reached the Connecticut Compromise, a deal that broke a deadlock and cleared the way for the arrival of a strong federal union to replace a loose confederacy of states.

What was central to that deal? The agreement that membership in the House of Representatives would be apportioned according to the white population of each state—plus three-fifths of their slaves.

Thus was a nation founded on quicksand, some historians say. Three-fifths gave the slaveholding states incentive to embrace slavery forever—the more slaves, the more political clout—as it helped radicalize abolitionists. To modern critics, it equated dark skin with being less than fully human—although southern delegates wanted to count slaves equally with whites. Northern delegates wanted slaves not to count at all. It was about regional power, not the humanity of the enslaved.

Cutting the deal with an indispensable minority, the majority was thinking short-term, said R. B. Bernstein, author of The Founding Fathers Reconsidered. Summer was fleeting, and the success of the constitutional undertaking depended on compromise. “The approach of the Founders was, ‘We’ll fix it now and let posterity sort it out,’” Bernstein said in an interview. “It’s like slapping a patch on your tire.”

By choosing expediency, they missed a chance to hobble slavery and avoid trouble. Although slaveholding was still legal almost everywhere, there was little enthusiasm for it among most delegates, and even a Virginian like George Mason could give a speech saying slaves “bring the judgment of Heaven on a country.” As Bernstein sees it, “A determined minority is hell-bent on protecting slavery, and the majority with a mild distaste for slavery has little or no inclination to do anything about it or to challenge the diehards from the Carolinas and Georgia.”

Central to delegates’ thinking was the assumption that slavery was waning as an agricultural model. “They didn’t reckon,” Bernstein said, “on the rise of King Cotton.” Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin lay six years in the future, with its ability to make slave agriculture more economic. Between 1793 and 1805, as profits rose, cotton production in the South exploded thirtyfold, increasing the demand for humans to plant, tend the fields, and pick the bolls.

If the delegates tiptoed around slavery, it was because the constitutional experiment was a minefield, says University of California at Los Angeles historian Daniel Walker Howe. The Framers hadn’t forgotten how divided the colonies had been over the question of independence from Britain in the first place. After four months of horse-trading in Philadelphia, the Constitution was signed by 39 of 55 delegates. “You couldn’t have had it be too antislavery or you wouldn’t have gotten all the states on board,” Howe said. Compromise was essential, “but in hindsight we can see that slavery came to flourish under the Constitution.”

Ratification showed the depths of division. Virginia agreed by a vote of 89 to 79. Almost 49 percent of the delegates to the convention of the largest state in the orchard of Revolution declined to partake of its new fruit. “This is a country that is very nervous about whether it will fall apart,” said Ron Chernow, biographer of George Washington and Alexander Hamilton. “Slavery is the most difficult and incendiary issue, and that’s the one least likely to be tackled. It was an abdication of responsibility, and the seeds were planted for the Civil War.”

Nevertheless, victories were scored against slavery in the early Republic. The northern state legislatures banned involuntary servitude, if by varying timetables. Princeton University’s Sean Wilentz says: “How many political entities in world history had ever abolished slavery? I can’t think of any. That was an opportunity seized upon.”

The Northwest Ordinance, passed by the Continental Congress in New York as the Constitutional Convention was meeting in Philadelphia, banned slavery north of the Ohio River, among other things. In his 1860 speech at Cooper Union in New York, Abraham Lincoln said this was proof that the Founders wished to give the federal government control over slave policy in the territories. That was a burning issue in Lincoln’s day, given that the Union was about to shatter over the question of whether slavery should be allowed to spread throughout the West. Lincoln looked to 1787 for moral authority.

But the Northwest Ordinance’s exclusion of slavery was not entirely purehearted, Bernstein said. It created states with “no slave past, and this was good—there was no sense of slavery as the default position. But it was bad, in that in Indiana and Illinois there was real racism against black people: ‘We want no slaves—or even free blacks—in this state.’ Some abolitionists didn’t want black people around.”

By drawing a line down the muddy Ohio, the ordinance underscored the great regional divide in America, along which cracks soon formed.

When ruling Federalists under President John Adams instituted the Alien and Sedition Acts to crack down on dissent, Jeffersonian Republicans were outraged. Two southern state legislatures issued protests in 1798: the Kentucky Resolutions, written by Thomas Jefferson, and the Virginia Resolutions, by James Madison.

These manifestos said states could “interpose”or, —as Jefferson said in a draft—use “nullification” to defeat the authority of objectionable federal laws. “In Madison’s mind, I don’t think he was trying to do much more than to say that the states have the right of political protest,” Jack Rakove of Stanford University said. “But Jefferson goes further and flirts with nullification, the idea that the states can actively interfere.” Federalists shuddered at the implications. Washington told Patrick Henry that he feared such a loosening of the Constitution’s bands might “dissolve the union.”

This is where the states’ rights movement got rolling. During the Civil War, future president James Garfield said the Kentucky Resolutions “contained the germ of nullification and secession, and we are today reaping the fruits.” A century later, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., speaking at the Lincoln Memorial, said Alabama Governor George Wallace’s lips dripped “with the words of interposition and nullification”—terms an anti-big-government partisan might embrace today, when, in some circles, arguments for states’ rights enjoy renewed favor.

To political columnist George Will, the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions were the most toxic Federal-era decisions of all. “Because of the prestige and intellectual weight of their authors,” he said, “they enabled advocates of disunion to have comfortable consciences.”

Secession became a buzzword above and below the Mason-Dixon Line. After Jefferson became president in 1801, some northerners said that the South had staged a coup based on the unfair advantage that the three-fifths clause gave it through apportionment of the Electoral College. In fact, southerners occupied the presidency for two-thirds of the years up to Lincoln’s election.

In 1803 there was secret talk of creating a breakaway Northern Confederacy in New England. The 1814 Hartford Convention echoed the nullification principles that Virginia and Kentucky had voiced. And by the 1830s, abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison wanted to scrap the Constitution for being hopelessly weighted toward Dixie.

Nothing in the constitution forbids secession—a serious oversight of the Framers, Howe said. “Believe it or not, the Articles of Confederation, which we so often trash as being inadequate, stated that they were ‘articles of perpetual union’ and implied that states didn’t have the right to secede. There isn’t anything like that in the Constitution, and it would’ve been nice if there had been.”

Another grievous weakness, some say, was the constitutional compromise that kept the transatlantic slave trade legal until 1808. Ships could continue to come over, their hideous holds crammed with suffering Africans. This was another concession to South Carolina, which argued that Virginia’s desire to end the trade was a selfish attempt to monopolize the lucrative breeding and export of blacks.

By allowing the trade to go on, the Framers thought they were giving a little air to a dying institution. But “slavery did not fade away,” said Richard Beeman, who wrote Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution. By 1808, 200,000 additional slaves were imported, “a very significant expansion. That was wholly unexpected.” The more blacks in the South, the less likely they could be liberated, because many whites “had an acute discomfort seeing them as free men.”

Fear of the enslaved fed on the killings of whites in rebellions like Toussaint L’Ouverture’s in 1790s Haiti, and Nat Turner’s in 1830s Southside Virginia.

As time passed, the fugitive slave clause of the Constitution rankled. “It makes Northern states complicit in slavery,” Beeman said. “It was adopted unanimously, almost without debate. That was the decision at the Convention that really contaminated the Constitution.” The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, one of the sharpest wedges in the Union’s division, reinforced it.

North and South were already drifting far apart by 1819, when the fight over admission of Missouri to the Union hinged upon the question “Could slavery be banned there?” There was talk of secession on both sides, and for the elderly Jefferson, this “fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror.” “Everything is obscured until the Missouri crisis,” Brown University historian Gordon S. Wood said. “The North realizes the South isn’t going in a Northern direction. From that moment the Civil War was inevitable.”

Perhaps war could have been averted had Virginia acted differently. “In 1789 it’s top dog, the state everybody looks to as the most powerful and richest,” Wood said. “Four of the first five presidents are Virginians, and the Virginia Plan is the model for the Constitution.” In the early nineteenth century, the state had a chance to provide further national leadership by dousing slavery, following the noble example of Washington, who freed slaves in his will.

But Virginia did no such thing. It shrank from a position of strength to weakness. Its population, once the largest in the country, fell behind that of fast-growing northern and midwestern states. As Tidewater farms stagnated, the most profitable export was slaves, shipped southwest to the booming Cotton Belt. The proud old commonwealth that had once helped shape the destiny of a nation became a beleaguered backwater—and some of its leaders grew shrill, dogmatic, and adamant for slavery.

Jefferson expert Peter Onuf warns against a romantic view of eighteenth-century Virginians’ high-mindedness and says their nineteenth-century successors merely continued a self-serving, pro-slavery direction. Brilliant Virginians, he says, helped fashion a Constitution that was “a great boon to slaveowners,” giving a powerful federal sanction to slavery with the three-fifths and the fugitive slave clause—unlike in Britain, where slavery’s legal protections had lately been weakened. As cotton production boomed, Onuf said, “The system worked really well for Virginians, giving them extraordinary opportunities.” With slavery thriving in Alabama and Mississippi, they migrated in droves to make fortunes. Virginia was wedded to human bondage, as it had been since 1619, when enslaved Africans disembarked on its shores at Hampton.

Should the Founders be blamed for the Civil War? Lately, some academics have taken a hard line against them. There has always been debunking of national heroes, said David Hackett Fischer, who wrote Washington’s Crossing, but now “real anger and rage” are bubbling up. Most younger historians would no longer call Jefferson, for example, a reluctant slaveholder who detested the institution and wished it gone. Instead, he is viewed as a man who saw in Africans a genetically inferior race and tried to expand slavery into the territories to cement his state’s political power.

Perhaps this goes too far, but certainly the Founders were fallible men incapable of envisioning a united, multiracial society in which whites and blacks lived in equality. That was a thing seldom if ever tried, and slave revolts painted a terrifying picture of what could go wrong.

Meeting that steamy summer in Philadelphia, the Constitutional Convention perhaps had problems enough without trying to solve the conundrum of slavery, already 168 years old as a North American institution. The task of uniting half a continent under a single government was almost overwhelming: almost never had it been attempted, as war-torn Europe, a crazy quilt of nation-states, showed. We might remember all this before too hastily assigning blame for the sowing of the seeds of the Civil War.

W. Barksdale Maynard is the author of five books on American history, including Woodrow Wilson: Princeton to the Presidency. He contributed to the autumn 2002 journal “When Plague and Pestilence Held Carnival,” a story of yellow fever in the Republic.