Page content

Captured in Watercolors

Elizabethan England’s First Glimpses of New World Fauna

Online Extras

Zoom in on John White's Watercolors

Nearly everyone with an interest in the images of early America knows the illustration below, An Indian werowance, or chief. . . . Less familiar is John White, the English gentleman limner who executed it. Almost obscure are White’s depictions of New World flora and fauna. For the first time in a generation, seventy-five of his renderings, owned by the British Museum, were exhibited in 2007 and 2008 at London, the North Carolina Museum of History, the Yale Center for British Art, and Virginia’s Jamestown Settlement in the show A New World: England’s First View of America. Chances are you know the Indian werowance from reproductions of a plate in Theodore de Bry’s A briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia, published in 1590. Its engravings, taken from White watercolors, showed scores of coastal Algonquins. But de Bry copied none of White’s birds, fish, reptiles, plants, insects, and shellfish. Which accounts for their relative unfamiliarity.

In the employ of Sir Walter Ralegh, White made five voyages to what are now North Carolina’s Outer Banks in efforts first to establish, and then to rescue, the Roanoke colony. Outbound in 1585, he sketched plants and animals in the West Indies and, in Carolina, the Indians. This tiger swallowtail butterfly he may have drawn in North Carolina. But, except for the common hoopoe, a European bird, the rest are Caribbean.

For lack of supplies, Roanoke was in 1586 abandoned. Back in England, White produced sets of watercolors that he likely presented in albums to Ralegh, perhaps Queen Elizabeth, her court, and investors in the colony.

With more colonists, White returned to Roanoke in 1587, stayed about a month, and sailed home for provisions just before he became grandfather of Virginia Dare, the first English child born in America. She became one of the Lost Colonists. White attempted twice to find them but failed.

He slips from history’s pages in 1593. But one of his albums survives. It resurfaced in 1788 when a London book dealer sold the volume to an earl. A descendant auctioned it in 1865 to an American, who sold it to the British Museum in 1866, where for forty years it went largely unremarked.

Because light fades watercolors, the British Museum exhibits White’s paintings just every thirty or forty years.

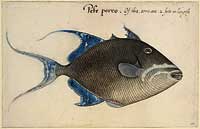

The Spanish called the tasty triggerfish Pese porco, which translates to “pig fish.”

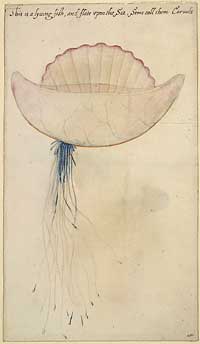

The western Atlantic’s man-of-war, which stings more fiercely than those in English waters, derives its name from a resemblance to a Portuguese caravel.

DDT poisoning nearly drove the eastern brown pelican to extinction in the 1960s, but, thanks to a ban on the pesticide, populations are recovering.

White’s rendition of the Bahamas’ dragon-like iguana was the first watercolor of the species painted in Europe. Wayfaring Spaniards and indigenous Indians prized its meat.

Inedible curiosities, the purple-clawed hermit crabs at left inhabit the abandoned shells of such molluscs as snails.

The land crab, probably drawn in Puerto Rico, also gave the artist trouble. He could not capture the shape of the eyes on the stalks of the animal as it scrambled in and out of the sandy holes which it lives in near the sea.

White mislabeled the burrfish at right a Gallo, mistaking this variety of the puffer for a spiny fish the English called a Dory.

The scorpion at left lies on its back. The specimens are probably West Indian.

White likely drew the common hoopoe, which makes sounds like a dog, in the Canary Islands.

The West Indies’ magnificent frigate bird is also known as the man-of-war.

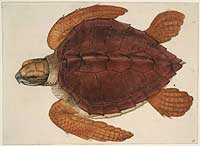

Now an endangered species, the loggerhead turtle made good eating.