Page content

"Things which seame incredible"

Cannibalism in Early Jamestown

by Mark Nicholls

Driven by desperate famine, a colonist in the Starving Time killed and ate his pregnant wife. Willy Balderson portrays the madman, Trish Balderson the unfortunate wife.

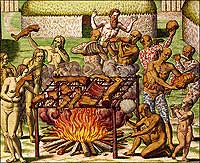

Likely part of purification or martial rites, cannibalism was practiced by some Indian tribes, here in Theodore de Bry's 1592 scene.

Boiled boot leather being eaten by Calvin Jenkins, left, and Patrick Strawderman when better sources of food had vanished.

Sir George Percy in a nineteenth-century portrait by Herbert Luther Smith, who copied an earlier work.

The English settlers who arrived in Chesapeake Bay aboard the Susan Constant during the spring of 1607 landed in a new world, mentally as well as physically. Expectations were high. Vast tracts of unexplored country beckoned with minerals, with rich land, and with the prospect of an easy trade route to the Indies. High hopes, however, were the while accompanied by profound fears. The Algonquian tribes of Virginia's Native Americans—the Powhatans—seemed friendly enough, to begin with, but there was already a "back catalogue" of incomprehension and mistrust in the relations between Indian and European, fueled by a belief that this state of affairs must necessarily endure. Englishmen sailing to North America anticipated savagery and barbarism in the peoples that they encountered; they found it hard to accept the humanity even of those who welcomed them and gave them succor. They expected none of their civilized norms, such as they were. These expectations, of course, proved self-fulfilling.

The human consumption of human flesh is as old as mankind—evidence survives from prehistoric and more recent societies across the world—but there was, in 1607, novelty in the word "cannibal," and novelty added to the frisson for the thousands of readers of travelers' tales, sitting in comfort back home. Contemporary writers, who knew their market, applied the term broadly, vaguely, and quite often for effect. Although Columbus refers to Canibales, predatory tribes living on the islands of the West Indies, the word unequivocally takes on its modern meaning in the mid-sixteenth century. "Cannibal" derives from a Spanish version of a Carib term meaning strong men. In the earliest records it is applied to intractable peoples encountered throughout the New World, those who resist the overtures of European traders and settlers. Antagonism of this kind was naturally unwelcome to those Europeans, and it had to be dealt with, militarily but also in the mind. One way to denigrate the truculent was to focus on their least palatable habits, and given the stigma attached on the eastern side of the Atlantic to the eating of human flesh, any suggestion that Native Americans devoured their fellow men, women, and children helped convey the notion that they were altogether less than human: fearsome enemies, expensive to defeat, but also fair game for bloody acts of reprisal.

The writings of George Percy, youngest son of the eighth Earl of Northumberland and a prominent member of the original band of Jamestown settlers, offer an insight into the mind-set of those early colonists. Like every other man in Jamestown, Percy had come across tales of cannibalism in the Americas. On the outward voyage, he repeated what he had heard about the natives of Dominica in the West Indies, that they would "eate their enemies when they kill them, or any stranger if they take them," would "lap up mans spittle, whilst one spits in their mouthes in a barbarious fashion like Dogges."

"These people," Percy wrote, "and the rest of the Ilands in the West Indies, and Brasill, are called by the names of Canibals, that will eate mans flesh."

Cannibalism was practiced in some contemporary Native American societies, particularly among tribes of the north and the west. Jesuits living with the Iroquois recorded it, like torture, among the victors over those defeated in battle, and there is evidence that these customs endured into the eighteenth century. But the Iroquois, Mohawk, and other peoples surrounded their cannibalism with strict and complex taboos; never simply gastronomic, it was usually confined to strengthening or purification rituals, or to the systematic humiliation of foes. Recorded instances are often tied up and confused with tales of human sacrifice, which may from time to time be seen as a sublimation of cannibalistic rites. There is no real evidence that such customs were found on the Virginian littoral, but a bad press is hard to shake off. Confronted with the Jamestown settlers and their suspicions, Indians of the Powhatan confederacy could not win.

When they captured Captain John Smith, they fed him, by his account, very generously. In this there were perhaps courtesy and a demonstration that the tribe was strong enough to eat well, but Smith, writing years later and aware his readership would welcome a good yarn, said he saw through the charade. Surely he had been fattened for slaughter. Vague tales of Virginian cannibals—always among the remoter tribes, just beyond the western horizon—persisted to the 1680s, when the minister John Clayton recorded tales of revenge cannibalism on defeated enemies.

Ironically, it is the English who demonstrably resorted to cannibalism in the early days of the Jamestown colony. When grisly reports reached England, carried by runaways on board the Swallow in the summer of 1610, they caused a stir. To allege cannibalism among one's erstwhile comrades was suspect in men guilty of deserting a beleaguered colony, but their tales won credence in London. If exaggerated, they were fundamentally accurate. When dearth and disease swept through Jamestown, reducing its population perhaps by 80 percent in the catastrophic Starving Time of 1609–10, some individuals had turned to cannibalism out of hunger. As Percy and other survivors told it, sporadic cannibalism was a manifestation of a partial breakdown in civilized society in the face of inescapable disaster:

A worlde of miseries ensewed as the Sequell will expresse unto yow, in so mutche thatt some to satisfye their hunger have robbed the store for the which I Caused them to be executed. Then haveinge fedd upon our horses and other beastes as longe as they Lasted, we weare gladd to make shifte with vermin as doggs Catts, Ratts and myce all was fishe thatt Came to Nett to satisfye Crewell hunger, as to eate Bootes shoes or any other leather some Colde come by. And those beinge Spente and devoured some weare inforced to searche the woodes and to feede upon Serpentts and snakes and to digge the earthe for wylde and unknowne Rootes, where many of our men weare Cutt of and slayne by the Salvages. And now famin beginneinge to Looke gastely and pale in every face, thatt notheinge was Spared to mainteyne Lyfe and to doe those things which seame incredible, as to digge upp deade corpes outt of graves and to eate them. And some have Licked upp the Bloode which hathe fallen from their weake fellowes.Percy, aware of the causes and trying to put events at Jamestown in context, turned to his books, mitigating these actions by pointing to precedents in colonies and settlements planted by England's European rivals. Even there some standards had been maintained. Whenever cannibalism occurs in the history of exploration in the New World, he suggests, it comes about in extreme circumstances, as an unwilling, necessary act:

If we Trewly Consider the diversety of miseries, mutenies, and famishmentts which have attended upon discoveries and plantacyons in theis our moderne Tymes, we shall nott fynde our plantacyon in Virginia to have Suffered aloane...The Spanyards plantacyon in the River of Plate and the streightes of Magelane Suffered also in so mutche thatt haveinge eaten upp all their horses to susteine themselves withal, Mutenies did aryse and growe amongste them, for the which the generall Diego Mendosa cawsed some of them to be executed, Extremety of hunger inforceinge others secrettly in the night to Cutt downe Their deade fellowes from of the gallowes and to bury them in their hungry Bowelles.

From left, Lindsay Gray, Dennis Farmer, Calvin Jenkins, Willie Balderson, Patrick Strawderman, and Dennis Strawderman.

There are earlier narratives that made the same point, including a few relating to the Newfoundland voyages. But Percy is saying something else here. Life in Jamestown, for all the conscious mimicry of English tradition, is fundamentally different from life back home. On the very edge of the known world, such security as there is in England does not apply. More than once in the course of their long ordeal the settlers must have given up hope, the ghosts of their dead comrades clustering about them in the emptying fort. These traumatized settlers clung to the distinctions that set them apart from their Algonquian neighbors while adopting fleeting new conventions and customs that were subsumed into a more stable, more English construct later in the century.

Here, graphically de-monstrated, is an "emergency society." Abnormal stresses lead to actions intolerable under a more established and comfortable way of life. Look, for example, at how laws are modified, or set aside, to suit a new, extreme life. English common law had come to discount evidence gained by torture, but in Jamestown the infliction of pain in pursuit of incriminating testimony is routine. Percy, in his capacity as interim president of the colony, tells us how he dealt with a man accused of killing, salting, and eating his pregnant wife.

When related by the Swallow refugees, the story had been indignantly rejected as a falsehood by the Virginia Company of London, the joint-stock enterprise led by Sir Thomas Smith that was responsible for the colony and its supply. But by the time that Percy wrote, about 1625, he no longer saw a reason to be coy. He conceded that he passed a sentence of death on the wretch—if for murder rather than cannibalism—having extracted an admission under torture, hanging his prisoner "by the Thumbes with weightes att his feete a quarter of an howere before he wolde Confesse the same." Though Percy did not say so, the man was burned alive, a punishment that follows no conventional penalty for murder under English law.

That punishment paled in comparison to the ad-hoc torments inflicted by Sir Thomas Dale. Deputy governor in 1611, Dale showed no patience with those "idell" colonists who preferred sloth or desertion to hard work. That impatience was apparent when he set out upriver to found a settlement, eventually named Henrico after the king's eldest son, Prince Henry. Deep in Powhatan territory, Dale took a tough line with recaptured deserters. Percy records the consequences:

Some he apointed to be hanged some burned some to be broken upon wheles others to be Staked and some to be shott to deathe, all theis extreme and crewell tortures he used and inflicted upon them To terrefy the reste for attempteinge the Lyke. And some which Robbed the store he cawsed them to be bownd faste unto Trees and so sterved them to deathe.

Yielding to the pangs of cruel hunger, colonists, portrayed by Calvin Jenkins and Carol Farmer, dug up corpses for food.

This is what the English did to their own. They were no more respectful of norms and guidelines in their relations with the Indians. The routine execution of spies may be familiar, but Percy also recounts the slaughter, in cold blood, of an Indian "queen" and her children, taken prisoner in a military operation. It is the fault of his followers, he writes, as the children are thrown into the water and shot while swimming, and the woman is led off and "putt to the sworde" in the woods. Reprisals against enemy captives were not unknown and had loomed large in the Elizabethan Englishman's experiences in Ireland, but the bloodlust shown by both sides in the early Indian wars, the absence of charity toward women and children, illustrates a mutual contempt and fear unusual in the wars between major European nations. Those at the mental frontier between "civilized moderation" and "unfettered savagery" engaged in a struggle for survival, finding that respect and self-esteem may vanish and that relentless siege and mounting hunger begin, step by step, to overwhelm nicer feelings. Percy is correct, up to a point. Incidents of the Jamestown kind of cannibalism must be seen in this context.

Can we, however, accept Percy's argument that cannibalism such as Jamestown's is never universally countenanced, that it is regarded as a repulsive action of last resort? Curiosities in the accounts make us wonder whether the full tale is being told. Reports, composed almost exclusively by the gentlemen among the settlers, say that the "lower orders" were the first to indulge in such acts; social norms were thus preserved in the written record. But who were the individuals who dug up and consumed corpses? They are never named. It is curious in so small a society that any man, wellborn or poor, could have enjoyed the privacy necessary to slaughter his wife and eat her over time, piece by piece. Did he get away with this because so many people were dying—and morale was so low—that one face more or less was not worthy of remark? Or was there connivance of some kind? Observe how the bodies of men, including at least one Indian, are buried before being surreptitiously dug up and consumed. Note, too, how carefully human flesh is prepared: "boiled and stewed with roots and herbs," "powdered," "carbonadoed." This suggests concerted action, perhaps widely beneficial, and perhaps verging on ritual. Is the implication of method and planning a later elaboration, or does it accurately reflect a starving man's obsession with food?

We touch on deeper fears: that human meat might prove addictive. One of the colonists, it is said, acquired the taste. He could not be restrained from cannibalism and had to be executed. True story, or a trope on where such bestial behavior can lead? From the Aztecs to the Fijians, history suggests that whole societies can develop a lust for human flesh, and that consumption ritualized keeps the craving within bounds. In this obsession, hunger, and pain, it is a relief to encounter a touch of bleak humor, directed not against Indians who had come up with a novel way of tormenting starving people, but rather against the influential men in England who had so signally failed to relieve the settlers' want:

Soe miserable was our estate that the happyest day that ever some of them hoped to see, was when the Indyans had killed a mare they wishing whilst she was boylinge that Sir Thomas Smith was uppon her backe in the kettle.

Mark Nicholls is a fellow, tutor, and librarian of St. John's College, Cambridge, England, who, in 2005, published in the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography a modern transcription of the only contemporary copy of George Percy's account Jamestown, his Trewe Relacyon. This is Nicholls's first contribution to the journal.