Page content

Acrostical Valentines

A Young Man's Fancy Turns to Fad: The Lovers' Literary Campaign of 1768

by Jon Kukla

Romance sprouted in the Virginia Gazette when puzzle poems spelled beloveds' names. Literary swain Adam Wright gazes on his paramour, Erin Wright, right, with Brooke Wellborn.

Friction between Great Britain and her American colonies eased after the repeal of the Stamp Act, but it was heating up in the spring of 1768. As Virginians contemplated the pre-revolutionary arguments of John Dickinson's Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, the chancellor of the exchequer in England, Charles Townshend, was drafting measures that would take a contingent of British troops to Boston in the autumn. During the lull in the imperial conflict, a love-struck poet turned the columns of William Rind's new Virginia Gazette into the MySpace.com of his day with "An Acrostical Valentine." Like the dogwoods blooming beneath the canopy of tall oaks and chestnuts, his project flourished amid the Gazette's columns of hard news. By August perhaps a score of other suitors had taken up their pens and joined the fad.

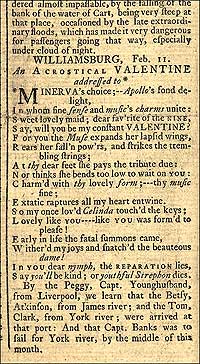

The surviving copies of Rind's Gazette preserve half a dozen clever verses honoring the young ladies of Williamsburg and its neighboring plantations. The first volley in the lovers' literary campaign of 1768 appeared in Rind's Gazette on February 11, three days before Valentine's Day. "An Acrostical Valentine" honored Miss Frances Lewis of a prominent Gloucester County family. Her admirer—whose identity has not been discovered—sang her praises in verses that, when the first letters were read vertically, spelled her name.

Minerva's choice;—Apollo's fond delight,

In whom fine sense and music's charms unite:

Sweet lovely maid; dear fav'rite of the nine.

Say, will you be my constant VALENTINE?

For you the Muse expands her lapsid wings,

Rears her fall'n pow'rs, and strikes the trembling strings.

At thy dear feet she pays the tribute due:

Nor thinks she bends too low to wait on you:

Charm'd with thy lovely form;—thy music fine:

Extatic raptures all my heart entwine.

So my once lov'd Celinda touch'd the keys:

Lovely like you—like you was form'd to please!

Early in life the fatal summons came,

Wither'd my joys and snatched the beauteous dame!

In you dear nymph, the reparation lies,

Say you'll be kind, or youthful Strephon dies.

For the young men and women of Williams-burg in 1768, acrostic verses were the equivalent of pop songs and Hallmark cards. If the closing lines of his Valentine poem are accurate, the author had been jilted by "Celinda" and now asked Frances Lewis to heal his wounded heart. His was an eternal theme of young love—published in the pages of the Gazette two centuries before Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys expressed identical hopes in "Help Me, Rhonda."

Abigail Schumann's Clementina Rind continued printing newspaper love poetry after her husband's death. Chad Jones assists.

The acrostic fad of 1768 was a lucky break for William Rind and his wife, Clementina. The couple had moved his printing business from Annapolis to Williamsburg two years earlier, after suspending publication of the Maryland Gazette to protest the Stamp Act. Like-minded Virginians, who said Joseph Royle's Virginia Gazette had been too deferential to royal authority, had high hopes for the new paper. In the competition for readers and subscribers, Rind made a shrewd business decision by welcoming the fad of romantic wordplay to the columns of his Gazette.

The second romantic acrostic of 1768 appeared in Rind's Gazette on February 18, a week after the first. Its author was David Mead, of Nansemond County—now Suffolk—singing the virtues of his fiancée, Sally Waters, in ten lines:

Most praise the gaudy tulips streak'd with red.

I praise the virgin lilly's bending head:

Some the jonquil in shining yellow drest;

Some love the fring'd carnation's varied vest;

Whilst others, pleas'd that fabled youth* to trace,

As o'er the stream he bends to view his face.

The exulting florist views their varied dyes;

E'n thus fares beauty in each lover's eyes.

Read o'er these lines, you'll see the nymph with ease,

She like the rose was made, all eyes to please.

Poet and editor alike were confident that their readers knew their flowers, but one of them was less certain about their familiarity with classical mythology. A footnote identified the "fabled youth" as Narcissus.

This second valentine poem was a success. Three months later, on May 19, the Virginia Gazette published by Purdie and Dixon announced that "on Thursday last David Mead, Esq., of Nansemond, was married to Miss Sally Waters, of this city, an agreeable young Lady."

By the end of February, the romantic acrostic poems fad had taken root in the pages of Rind's Gazette. Among the newspapers that survive, we find a tribute in March to a Miss Nelson of Yorktown, perhaps kin to Secretary Thomas Nelson, a member of the Governor's Council. In April, two suitors who identified themselves with the initials G. and M. offered poems in praise of Nancy Murray and Catherine Swann of Surry County.

By mid-May, the columns of Rind's Gazette were bulging with verbal puzzles and poems. An acrostic written by I. E. contributed nine lines of praise for Lucy Cocke, whose father was Williamsburg's mayor.

Lovely dear maid, my gen'rous tale approve,

Untaught in verse to sign the fair I love;

Could you but know the dictates of my heart,

Your gentle soul wou'd healing balm impart.

Conquer'd by you, what raptures seize my breast,

O say dear charmer, will you make me blest?

Constant I'll prove as light to early day,

Kind as bright Phoebus to his darling May,

Each hour, each moment, shall my love display.

By Phoebus was meant the sun.

For young Virginians who were "untaught in verse," as Lucy Cocke's admirer said he was, the creation of an acrostic poem was a feat. Others agreed with the English essayist Joseph Addison, who said acrostics were a form of false wit "in which a writer does not show himself a man of a beautiful genius, but of great industry." Acrostics and puns, Addison wrote in The Spectator, were devices used by "undisputed blockheads ...to entertain ambitious thoughts, and to set up for polite authors."

Addison's opinions, however, had no effect on the fashionable young Virginians whose thoughts turned to poetry in the spring. Two weeks after Rind opened the columns of his Gazette, some of Addison's industrious blockheads were reaching for greater verbal challenges as they sang the praises of young women. The most ambitious form was a word puzzle, not unlike those in the back pages of Harper's or the Atlantic Monthly, that made its first appearance in Rind's Gazette on February 24, 1768. An "Acrostical Rebus on Miss Betty of King William" consisted of eleven lines of rhyming riddles. Two examples suffice:

A flower whose fine fragrance few others excel;

What the gossips assembled most rapidly tell.

Once all the riddles were solved, the first letters of the answers would spell out Betty's name.

What were the answers to these riddles, and who was Miss Betty of King William County? We may never know. Despite the best cooperative efforts of Virginia's major libraries, there are gaps in the files of all the Virginia Gazettes from the eighteenth century—and one of those missing weekly papers contains the solution to the "Acrostical Rebus."

Similarly tantalizing is a lost "Paradox," com-posed by A. B., about a young lady who seemed four times older than the number of her birthdays. We know that Rind published the puzzle May 5, 1768, though no copy of that Gazette survives, because Rind published the answer a week later. Under the heading "Paradox in the last Gazette, answered by Miss S.R. to A.B.," the solution was embedded in lines of verse: "On Feb: the nine and twentieth day, your charming Celia young and gay, / First breath'd this vital air.

This rhyming declaration of hopeful love picked out Miss Frances Lewis's name in the first letter of each line of the poem.

Frustrating as these gaps in the record may be, at least we feel clueless because issues of the Virginia Gazette have been lost. Rind's readers had no such excuse. By the summer of 1768, the more complicated verbal puzzles were driving some adults crazy. "I have sometimes observed, with great pleasure, that your paper is become the channel for lovers to celebrate their particular favorites," a subscriber wrote from the port city of Norfolk in August. "I think every one that sends you acrostical rebusses ought to send you the Lady's name they thereby intend to celebrate, verified in due form, to be published in case no other answer should appear."

Signing himself "J. Tar," meaning Jack Tar, as sailors were called, this industrious fellow closed with a ten-line acrostic to his own "charming maid," Nelly Davis.

In accord with the motto on the masthead of the paper—"Open to ALL PARTIES, but influenced by NONE"—William and Clementina Rind published Jack Tar's advice. They did not succumb, however, to his impatience. Their encouragement of the wordplay fad had proven good for business. Scattered throughout the columns of their Gazette one finds occasional hints that young ladies were reading and contributing to the project. The puzzle about leap-year birthdays, for example, had been "answered by Miss S.R."

Clementina Rind, who continued to publish the Gazette after her husband's death in 1773, probably had her hand in this editorial policy. In the autumn of 1768, as Rind prepared the coming year's Almanack for publication, he filled its pages with "Enigmas, Acrostics, Rebusses, Queries, Paradoxes . . . for the Instruction, Use and Diversion of BOTH SEXES." The editor's appeal to an expanded readership was proclaimed in its revised title—The Virginia Almanack, and Ladies Diary, for the Year of our Lord 1769—and in its preface. "I have," William Rind wrote,

determined to introduce a Ladies Diary into Virginia, not doubting but many of the ingenious Ladies of this Colony will not only approve, but encourage such an entertaining and useful Work, in which they will have a certain Opportunity of carrying on a poetical Correspondence with their Friends.

The editor was confident male readers would find the new Almanack and Ladies Diary beneficial as well. "The Gentlemen," he said,

will readily embrace an Opportunity that opens to them so fair a Path to a friendly Correspondence with the most Ingenious of the Fair Sex; and who can doubt, but that they will chearfully exert their Talents . . . to the Entertainment and Diversion of the most amiable Part of Creation.

The new Almanack and Ladies Diary offered another feature that appealed to less ingenious readers: the solutions to verbal puzzles in the pages of the newspaper previously unsolved. Prominent among the Almanack's new crop of puzzles was this "Acrostical Answer to an Analytic Rebus in Mr. Rind's Gazette, for June 2, 1768," another issue that does not survive. By choosing the new Almanack and Ladies Diary over its mundane rival, published by Purdie and Dixon, perplexed Virginians like Jack Tar of Norfolk learned that it was Alice Corbin, daughter of a wealthy and prominent planter-statesman, whose identity had eluded them for months:

Accept, fair Nymph, dear Friendship's Tribute due:

Lo, here she pays her kind Respects to you;

In this first Di'ry, as on Wings of Fame,

Constrains the Muse to sing thy dear-lov'd Name,

Echo through Woods and Groves resounds the same.

Charming as is the royal Queen of Love;

Obedient as the rolling Orbs above;

Religious too, in ev'ry chearful Strain;

Blest with good Sense;—engaging, yet not vain;

Ingenious, virtuous, delicate and true;

No more my bounded Theme admits!—Adieu.

As with all fads, however, the lovers' literary campaign of 1768 dissipated nearly as suddenly as it had arisen. One acrostic poem appeared in the extant issues of Rind's Virginia Gazette in 1769—although, in a very different vein, Purdie and Dixon printed an acrostic denunciation of the English radical John Wilkes. The form enjoyed a brief revival in Williamsburg's newspapers on the eve of the Revolution. Prompted by an acrostic to Molly Dixon that appeared in Purdie and Dixon's Gazette in January 1773, the Rinds published acrostic tributes to Nancy Langley, Peggy Ritchie, Polly Harris, Betsey Tomkins, and Sally Cary between March 1773 and December 1776.

The American Revolution had begun. War and politics dominated the columns of Williamsburg's newspapers. The final acrostic in the Virginia Gazettes of 1776 honored Sally Cary. The fate of the acrostic poem fad that had begun at Valentine's Day in 1768 was implicit in the subsequent notice of her marriage: "Thomas Nelson, jun. Esq; captain in the first Virginia regiment, to Miss Sally Cary, eldest daughter of Wilson Miles Cary, Esq; of the county of Fluvanna."

Jon Kukla is executive vice president of the Patrick Henry Memorial Foundation in Brookneal, Virginia, and author of the forthcoming book Mr. Jefferson's Women (Alfred A. Knopf, autumn 2007). This is his first contribution to the journal.

Learn more:

- The Printer & Binder

- Gentlewomen of the Press from the Spring 2003 Journal.