Page content

Wills Simple and Elaborate:

Bequests, Gifts, and Legacies

text by James Breig

photos by Dave Doody

The will of Peregrine White, first child of the Plimoth Pilgrims, in which he stipulated his son maintain "one cow" for his wife.

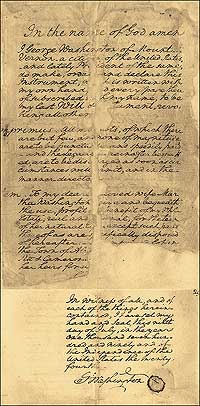

In his will, George Washington styled himself a citizen of the United States and "lately President of the same."

Courts appointed trustworthy men to inventory the departed's earthly goods—as in this scene portrayed by Colonial Williamsburg's Warren Vaughn, left, and Ben Knecht. Basic information in reconstructing history, wills and inventories tell us what people owned and of what value.

Ken Wolfe with the Kirby silver collection in the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum—more than 1,000 pieces of plate silver. Gifts that people leave Colonial Williamsburg in their wills support and enrich its mission of preserving and presenting colonial life.

James Bray of Williamsburg made bequests to his children and grandchildren, as well as "all my wearing Cloths" to Robert Wade.

After Bray's death in 1725, an inventory of his estate—down to his "chocolate & coffee plate"—was added to the end of his of will.

Near the start of the eighteenth century, on July 14, 1704, Peregrine White of Marshfield, Massachusetts, the first child born in America of the Pilgrims the century before, "Being aged and under many Weaknesses and Bodily Infirmities But of Sound disposing mind and memory," signed his last will and testament. He was eighty-three. First, he made sure to "Humbly commit my Soul to Almighty God that Gave it and my Body to decent Buriall." Next, he instructed his executors to pay his debts and funeral expenses. Then, he bequeathed to his "wellbeloved wife," Sarah, "all my Goods and Chattels not otherways disposed of." His son Daniel would come into "my Great table" and "my Joynworke Bedstead and Cupboard." A grandson got White's gun. Just before making his mark at the bottom of his will, White left "each of my ...Daughters one painted chair and a cushion."

At the other end of the 1700s, in the summer of 1799, George Washington, identifying himself as "a citizen of the United States, and lately President of the same," wrote the same sorts of paragraphs. He ordered his debts be paid and his "dearly beloved wife" receive "the use, profit and benefit of my whole Estate, real and personal, for the term of her natural life," including "my household and kitchen furniture of every sort and kind, with the liquors and groceries which may be on hand at the time of my decease."

"Upon the decease of my wife," Washington wrote, "it is my Will and desire, that all the slaves which I hold in my own right, shall receive their freedom." By those words, Washington, who died a few months later, left behind not only his material goods but an inheritance of liberty.

As the seventeenth century turned into the eighteenth, attitudes toward wills changed. Historian Holly Brewer said that in the 1600s, "wills were more creative and less legally formalized. Someone wrote down what someone else said on his deathbed. It was conversational. In the eighteenth century, it became more formal."

In 1711, Virginia adopted an act "directing the manner of granting Probats of Wills, and Administration of Intestates Estates." It delineated everything from the oath to be taken by executors to what happened to crops when their owner died before the harvest. The law directed the plantings to be left in the ground until December 25, then harvested and appraised by the executors. The slaves required to bring in the "Indian Corn, Wheat, or other Grain, or Tobacco" were not to be delivered to the heirs until Christmas Day.

In eighteenth-century Virginia, anyone over twenty-one could compose a will—except for married women. Unmarried and widowed females, however, could designate who got their belongings; an example is Susannah Riddell of Williamsburg, a Loyalist widow who left slaves and a house when she died in 1785.

Dying people did more than designate who would get their land and goods, Brewer said. They sometimes left instructions to their children or warned their heirs that "they would not get something if they did something wrong, for example, marrying the wrong person." In his 1813 will, John Tyler of Virginia's Charles City County instructed his sons to "ever be brotherly and affectionate to each other." Louis XVI of France, guillotined in 1793, left "my soul to God" and sought pardon from "all those whom I have inadvertently offended." The will said: "I recommend strongly to my children ...to remain always united amongst each other; to be submissive and obedient to their mother, and gratefully sensible of all the care and trouble she has had on their account." Of his son, the Dauphin, the king said: "Should he ever have the misfortune to be king, ... he ought to sacrifice every thing to the happiness of his fellow citizens." Louis's successor, Napoleon, left a testament instructing his son to take up the motto "Everything for the French people."

In our time, the bequests of values as well as valuables are memorialized in what have become known as ethical wills. Books and Web sites offer suggestions for them. Such wills might contain stories of the deceased's childhood, lists of favorite foods or vacation sites, an outline of spiritual beliefs, suggestions for how to live well, or a catalogue of mistakes made and to be avoided by heirs. Modern will writers may also do something that unites leaving tangible items and intangible values: a bequest to a charity.

Brewer said that colonial will writers occasionally gave money to charity schools, such as the one for Indians in Williamsburg, "or for a sermon to be given annually on the date of their death in perpetuity." In 1645, Richard Vaughan of Virginia bequeathed half-a-ton of tobacco "towarde the building a howse for gods service." Ebenezer Wells of Deerfield, Massachusetts, who died in 1758, specified in his will that the Church of Christ in his town should receive a "good silver tankard." He directed his executors to see to the drinking vessel's creation and presentation. In Surry County, Virginia, an Episcopal church benefited from the 1764 bequest of Elizabeth Stith, who gave £50 "to purchase an Alter piece...I would have Moses and Aaron drawn at full length holding up between them the Ten commandments." If there was money left over, she asked it to be spent for "the Lord's prayer in a small Fraim" and the Apostles' Creed in another.

Benjamin Franklin bequeathed money and possessions to colleges, schools, and the "building of churches." Some of his books went to the Philosophical Society of Philadelphia, the American Philosophical Society, and the Library Company of Philadelphia. In addition, "one hundred pounds sterling" was given to free schools in Boston. His uncollected debts, some decades old, were passed to the Pennsylvania Hospital, "hoping, that those debtors, and the descendants of such as are deceased ...may ...be induced to pay."

James Lewis Macie, an English scientist born illegitimately in France in 1765, consulted the book Plain Advice to the Public to Facilitate the Making of Their Own Wills. It came with "forms of wills, simple and elaborate." By the time he died in Italy in 1829, Macie had adopted the surname of his father, Hugh Smithson, the first Duke of Northumberland. As James Smithson, he left the bulk of his estate to his nephew—with the proviso that "In the case of the death of my said Nephew without leaving a child, ...I then bequeath the whole of my property ...to the United States of America, to found at Washington, under the name of the Smithsonian Institution, an Establishment for the increase & diffusion of knowledge among men." The nephew died childless, and more than $500,000 came to America as seed money for what is now a network of museums.

The obverse of generosity to schools, churches, and other charities was the treatment of slaves as property that could be left to heirs or disposed of, as exemplified in the 1719 will of Orlando Jones of Williamsburg, who was Martha Washington's grandfather. He gave his son and daughter more than a dozen slaves "forever." In her 1781 will, Ann Temple of King William County, Virginia, passed along to her granddaughters "my negroe boy Platoe," "my negroe wench Alice," "my negroe girl Betty," and "my negroes Juno, Luvina & Patience." In the 1786 will of Peter Randolph of Sussex County, Virginia, after commending his "soul to God who gave it me," he directed "that my negro man Archer," three horses, and a dozen sheep "be sold to discharge my debts."

The last testaments of the early citizens of Williamsburg provide details about how they lived and who owned what. After someone died, a court appointed three people—usually neighbors—to inventory and appraise the deceased's property to determine the departed's wealth. The 1772 inventory of merchant Joseph Scrivener's estate tells Colonial Williamsburg historians he possessed such items as four casks of vinegar, a copper kettle, a broken mirror, 150 bushels of coal, and "1 plain gold watch." When the Virginia Gazette reported that items from Scrivener's estate would be sold, the newspaper catalogued "four valuable Negroes, a cart and five horses, a riding chair and his house and lot." Similarly, John Stott, a Williamsburg watchmaker, left an estate in 1748 that included five bedsteads, seven tables, chairs, a corner cupboard, a desk, two clocks, two looking glasses, pictures, brass andirons, seven candlesticks, books, china, earthenware, stoneware, pewter, two wigs, and his watchmaking tools.

Modern wills benefit Colonial Williamsburg another way: through legacies that have provided funds for preservation of the historic town. Ken Wolfe, director of planned giving, said that visitors see the generosity of their predecessors. "Bequests of objects and antiques are the most visible things," he said, "but, in a sense, everything at Colonial Williamsburg is helped by bequests." He ticked off several examples: more than 1,000 pieces of rare Sheffield plate silver, collections of early American furniture, a bequest to fund the re-creation of eighteenth-century wallpaper, and a legacy to pay for expert speakers to come to Williamsburg.

Gifts sometimes come from surprising sources, Wolfe said, such as a California visitor who came to Virginia once or twice and was so impressed that he left $1 million to the restored town. A retired educator who lived in a modest home in Michigan, a recent widow, wrote a letter in 1980 to ask how she could leave her estate to Colonial Williamsburg. She wrote, "I believe strongly in its purpose" and loved its "authenticity and charm," which she and her late husband had enjoyed during visits in the 1960s. When she died in 1994, Colonial Williamsburg received nearly $2.7 million. "She was a saver, not a spender," Wolfe said, "and she had a passion for Williamsburg."

He comes across emotional attachments when talking to people about bequests. "They consider Williamsburg a part of their family," Wolfe said. As they age, "They ask themselves what their legacy will be and reflect on their values. They have a belief in the ideas and ideals behind the founding of the country. Their first visit is often transformational; it bowls them over. They come in school groups, or they honeymoon here, or their parents brought them and now they bring their own children. Part of it is the place, and part is the people, even the staff in the hotels. Other historic sites are much more static, while we keep changing and evolving. That keeps us vibrant in people's minds."

Through their lists of property and goods, wills are expressions of material wealth. But those often come alongside statements of humility that may have been occasioned by open graves yawning before the signatories. Perhaps no one was ever more ready to shake off the vain honors of mortal life than Francis Fauquier, a beloved lieutenant governor of Virginia who died at the Governor's Palace in Williamsburg in 1768. In his will, he refers to "the uninformed Mass of Clay" that will remain after his soul has returned "into the Hands of a most Merciful and benevolent God." If he dies of "any latent disease," the governor ordered the physicians who treated him to open his body so "that the immediate cause of my disorder may be known, and that by these means I may become more useful to my fellow Creatures by my Death than I have been in my life." After the surgeons were done with his "unfeeling Carcass," Fauquier requested that it be "Deposited in the Earth or Sea as I shall happen to fall, without any vain Funeral Pomp and as little expence as Decency can possibly permit."

James Breig, an Albany, New York, editor and writer, contributed a story about eighteenth-century optics to the summer 2006 journal.