Page content

Captain Jack Jouett's Ride to the Rescue

Did Virginia's Paul Revere Spare Thomas Jefferson the Acquaintance of a British Hangman?

by Ed Crews

As the British moved to capture Thomas Jefferson and other Virginia officials, Jack Jouett, portrayed by Colonial Williamsburg's Stuart Lilie, rode through the night with a warning.

LATE IN THE EVENING, Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton and 250 mounted British soldiers reined up near Cuckoo Tavern. The troopers were hard, dusty hours in the saddle. They had mounted before dawn at a Hanover County camp and pushed themselves more than twenty leagues across the Virginia Piedmont to this Louisa County way station. But the riding of that day—June 3, 1781—was not over. Before it was done, a tavern patron, putting down his drink, would gallop into the night and the history of the American Revolution, and dismount, to be remembered as Virginia's Paul Revere. That man was Captain Jack Jouett of the Virginia militia, a fierce and astute patriot who understood why Tarleton was there.

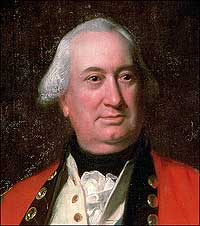

About three weeks before, Virginia's government had been spooked out of Richmond by the invading redcoats of General Lord Charles Cornwallis. While skeddadling, lawmakers paused to vote to regroup May 24 at Charlottesville, about forty miles northwest, as a bird flies, from this out-of-the-way inn where Jouett was taking refreshment. Tarleton, a capable, feared, and despised officer—"Bloody Tarleton" the Continental Army called him—was headed that way. Jouett saw that Tarleton intended to capture Governor Thomas Jefferson and such other officials as Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee, Benjamin Harrison, and General Thomas Nelson Jr.

Jouett took a mount and spurred away into the night, determined to get to them before Bloody Tarleton.

PERHAPS NO EXPLOIT of the Revolution is more obscure to America, or better known to Virginia, than Jouett's dead-of-night dash. If he is yet overlooked in Texas-qualified textbooks, for decades Virginia elementary school teachers have told his story to new Old Dominion generations, often in exciting and romanticized ways.

Jefferson was home at Monticello when Jouett found him and told him that Colonel Banastre "Bloody" Tarleton was closing in.

They say Jouett spared Jefferson the indignity of capture and may have saved Monticello's master from a British hangman—as Armistead C. Gordan Jr., a University of Virginia professor, wrote in a 1925 issue of Commonwealth Magazine:

Had Jack Jouett not frustrated Tarleton's foray, a disheartening and even fatal blow might have been occasioned by the simultaneous capture of Jefferson, Henry and three signers of the Declaration of Independence at a juncture when Continental fortunes were at a critical ebb.

Still, beyond Virginia grade schools, Jouett's adventure is little remembered or remarked. Monticello, Jefferson's just-south-of-Charlottesville home, has about 460,000 visitors a year. Dan Jordan, president of its steward, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, says people rarely recall enough of Jouett's ride to the rescue to ask about it.

HISTORIANS, HOWEVER, remember that in 1781 the British invaded Virginia during a desperate passage of Jefferson's governorship. Jordan said, "It's hard to think of a worse time to be governor than during Jefferson's two terms. Henry Adams reference to 'the paucity of the means; the immensity of the task' says it all. Jefferson held office with virtually no power or authority. The governor then was called a 'signing clerk.' Yet Jefferson had to rally the commonwealth against invasion by lead elements of the most powerful army and navy in the world."

In 1779 and 1780, Governor Jefferson grappled with a ruined state economy, runaway inflation, endless calls for supplies and troops, and a despised conscription policy. He did not rise to the occasion.

Charles Bryan, president and chief executive officer of the Virginia Historical Society, said, "Serving as governor was not the highlight of Jefferson's life. It was a difficult job, but he did not demonstrate clear executive leadership. Jefferson had served in the General Assembly, and had written the Declaration of Independence. Yet he had no executive experience. He was new at the role. It cannot be said he did particularly well at it. You get the impression that he was overwhelmed by the responsibilities."

Those responsibilities grew in 1781. The year opened with a raid up the James and Appomattox Rivers by Benedict Arnold. The expedition did not amount to much, but it signaled the start of strategic British operations in before-bypassed Virginia. During the next few months, the British established a force in Tidewater that combined in late spring with Cornwallis's large command, which had been campaigning further south. Cornwallis intended to conquer Virginia, once the largest and richest English colony, to cripple American's war effort.

Operating north of Richmond, chasing Lafayette, Cornwallis received an intercepted American dispatch reporting the presence of Jefferson and members of the legislature in Charlottesville. To his mind, they were legitimate military targets, and he ordered Tarleton to capture them.

Tarleton faced a seventy-mile ride, but he believed that he could reach Charlottesville before American spies noticed his absence. The raiders rested about noon and hurried toward Cuckoo Tavern. Jouett saw them there about 9:30 p.m.

He and his father had signed the Albemarle Declaration, a renunciation of loyalty to King George III. His father and brother Matthew were also captains in the Virginia Militia, as was brother Robert in the Continental Army. Jack Jouett was twenty-six years old, 200 pounds, and six-feet-four. Contemporaries described him as handsome, a superb marksman, and an accomplished horseman.

He stole away as Tarleton, dismounting at a nearby plantation, gave his men three hours rest beginning at roughly 10 p.m. Jouett pounded through the night. He reached Monticello near daybreak, warned Jefferson, and headed to Charlottesville to raise the alarm.

Jouett reached Monticello at dawn of June 4, 1781, and found Jefferson, Colonial Williamsburg's Bill Barker, preparing for breakfast.

Extra: View an image of Stuart Lilie portraying Jack Jouett and Bill Barker portraying Thomas Jefferson awakened in the middle of the night.

JEFFERSON APPARENTLY took Jouett's warning seriously but thought he had ample time to get away. Jefferson enjoyed breakfast, sent his family to safety at Enniscorthy Plantation fourteen miles away, and began sorting state papers for packing or destruction. Technically, he was no longer governor. His term expired June 2. The government, however, would not appoint his replacement, General Nelson, until the fifth, and Nelson would not take office until the twelfth.

Within a couple hours of Jouett's departure, another American rider came. Captain Christopher Hudson told Jefferson that enemy troops were immediately behind him, working their way up the mountain to Jefferson's home. Jefferson decided to check. He strapped on a light sword, walked to a vantage point away from the house and trained his telescope on the city. He saw no activity. He was walking home when he noticed that the sword was missing. Assuming he had dropped it, Jefferson retraced his steps to his viewing point and took another look at Charlottesville. Tarleton's red-and-green uniformed men filled the streets.

Jefferson jumped on a stallion and flew into the woods, bound for the Shenandoah Valley, eighteen miles west beyond the Blue Ridge. He disappeared just as an enemy detachment reached his front door. Jefferson spent the night at a nearby home. Most legislators departed safely, although hurriedly, thanks to Jouett, to reconvene June 7 in Staunton.

TARLETON captured a few people, among them legislator and frontiersman Daniel Boone. He detained them briefly, and paroled them. The British did comparatively little damage. Monticello was unharmed, though some wine disappeared. Tarleton left Charlottesville on June 5. With his departure, the British considered the matter closed. Cornwallis wandered to Yorktown, where General George Washington trapped his army in October and forced its surrender.

Neither Cornwallis nor Tarleton suffered for his failure to shut down Virginia's government. Cornwallis returned to Great Britain after Yorktown and enjoyed widespread popularity. Tarleton had a long, successful military career and served in Parliament.

When it met again in Staunton, the Virginia legislature voted to investigate Jefferson's conduct during the final dozen months of his governorship. He suspected Patrick Henry was behind the embarrassment. Jefferson biographer Dumas Malone wrote: "This event marked the nadir of the entire public career of Thomas Jefferson." In December, Jefferson presented a three-day defense of his administration, and both houses of the General Assembly unanimously passed a resolution commending Jefferson's performance as governor

Nevertheless, charges of fleeing in cowardice in the face of the enemy plagued him after the war. In 1796, his rival Alexander Hamilton wrote in the Gazette of the United States that the "governor of the ancient dominion dwindled into the poor, timid philosopher and, instead of rallying his brave countrymen, he fled for safety from a few light-horsemen and shamefully abandoned his trust!"

The issue resurfaced in the presidential election of 1800. Supporters of John Adams called opponent Jefferson an anarchist, an atheist, and a coward, referring to his flight from the British. Jefferson found the last charge particularly galling.

"It stung Jefferson badly," Jordan said. "He was thin-skinned to begin with, but this was a serious charge. It was easy for the critics to use it."

A grateful Virginia General Assembly voted June 15, 1781, to reward Jouett with a sword and a brace of pistols. The state's poverty explains why Jouett got the pistols in 1783 and the sword in 1804.

In 1782, Jouett moved beyond the Alleghenies to what is now Kentucky but then was part of Virginia. He married Sally Robards in 1784. Three years later, he won a seat in the General Assembly and took a leading role in the effort to make Kentucky a separate state. He served that state four terms as a legislator. He died on March 1, 1822, on his farm, Peeled Oak, in Bath County, Kentucky.

JOUETTE'S RIDE IS an interesting and exciting story of the Revolutionary War. But was it significant? To answer that question, we must ask another: Could the capture of Jefferson and other leading Virginians have changed the war's outcome? Scholars say it hinges on two issues: Jefferson's fate if captured and the impact of that fate on the colonial cause.

Bryan said, "There is speculation that Thomas Jefferson would have been brought to the Tower of London and tried for treason. This could have happened, but there is no historical evidence that this was the plan. He was a traitor, and, in the worst case, this could have happened. All the leaders of the patriot cause knew that their lives were at stake for the position they'd taken on American liberty, and they accepted the risk."

Revolutionary War scholar Philander Chase, a senior editor of the George Washington papers at the University of Virginia, is not convinced the British wanted to hang Jefferson. "We really don't know what might have happened to Jefferson," Chase said, "but his experience might have been like that of Henry Laurens.

After first seeing nothing, Jefferson spotted the approach of British troops on a second look and vacated Monticello.

Extra: View an image of Barker as Jefferson observing Monticello from a safe distance.

"Laurens was from South Carolina. He was a member of the Continental Congress and served as its president. In September 1780, he went to Europe on a diplomatic mission. The Royal Navy captured him, and British officials imprisoned him in the Tower of London. He was not abusively treated, although his health suffered. He was held about a year. Officials offered him a pardon, but Laurens refused to accept it. He eventually was exchanged for Cornwallis after Yorktown.

"Thomas Jefferson was prominent, but he also was a young man who did not have the reputation he enjoys today. Neither the British nor Americans at the time made much of his writing the Declaration of Independence. His status for that achievement would grow over time until it reached the large proportions it enjoys today. Jefferson's capture would have been a big deal, but it would not have been as large a matter to his contemporaries as it would be to us with our appreciation for what the document means to the nation."

Bryan said Jefferson's capture might have affected morale but not American victory. Cornwallis still would have gone to Yorktown and defeat.

But that would not make Jouett any less a hero.

"Stripping away all romanticism, Jouett still is consequential and deserving of recognition for his courage, sagacity, and patriotism," Monticello's Jordan said.

"Here was a man who got the sense that the British were up to something, figured it out, and rode to Charlottesville to warn the governor and the legislators. Stripped to the basics, he was a hero. He should be remembered and honored for his valor. His patriotism is worthy of emulation. He acted without regard for his own safety and on the behalf of the best interests of his people. We should respect what he did and learn from it."

Edward R. Crews is a regular contributor. Like countless other Virginia schoolchildren, he learned of Jouett's ride in fourth grade.