Page content

"The Monstrous Absurdity"

The Gunpowder Theft Examined

by Mary Miley Theobald

Thieves in the night. Governor Dunmore stole a march on Williamsburg by removing the gunpowder from the Magazine while the town was asleep. He said publicly it was for Virginia's protection, but privately that it was for the crown's.

Extra Images:

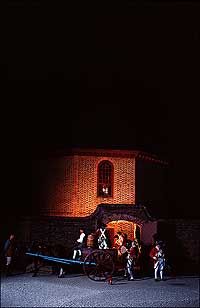

1. In a reenactment of the “Gunpowder Incident,” British marines (in red) remove arms from the Magazine in Williamsburg.

2. The Magazine as it appears today in Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area.

A Scot named Miller first leaked the word. The armorer hired to clean and repair the public arms, he was the first to know. Lord Dunmore, governor of Virginia, had ordered the gunlocks taken off most of the firearms in Williamsburg's Magazine and was planning to seize its stores of gunpowder.

The city, the capital of the colony, treated the rumor seriously—for about a week. Citizens patrolled the streets and guarded the Magazine at night. But, according to a historian writing thirty years after the event, "at length disbelieving it, they grew a little negligent and on Thursday night the 20th" of April, 1775, "discharged their guards."

Waiting for such an opportunity was redcoat Lieutenant Henry Collins, captain of the armed schooner Magdalen. Under cover of darkness, he and twenty sailors stole up to the Magazine and were loading a wagon with barrels of gunpowder when someone raised the alarm. Before townspeople could stop them, Collins and company fled to their ship on the James River with fifteen half-barrels of powder.

Drums beat. Angry men gathered near the Governor's Palace. Armed hotheads were ready to storm the residence and force Dunmore to return the powder, but leading citizens persuaded them to let their elected officials try a peaceable approach. The next day, Peyton Randolph, speaker of the House of Burgesses and president of the first Continental Congress, the mayor, and others called on Dunmore. They applied for an explanation.

The governor said rumors of a slave insurrection had prompted him to have the powder taken from the brick Magazine, which he termed "a very insecure depositary," and loaded on the twenty-gun man-of-war Fowey, "a place of perfect security." The deed had been done at night, he said, to shield the population from undue alarm, and they had his word of honor that he would return the powder inside half an hour if the slaves rose.

Colonial Williamsburg interpreters Bill Weldon, right, as patriot leader Peyton Randolph and Steve Holloway as Williamsburg's mayor pass the Governor's Palace gates to protest against removal of the gunpowder.

Extra Image: Peyton Randolph – portrayed here by Wayne Moss – rallies his fellow citizens following Dunmore’s order to remove the gunpowder under cover of darkness.

Repeating rumors of slave revolts, Governor Dunmore, here Phil Shultz, quicksteps his way round objections to removal of the gunpowder.

Extra Images:

1. Phil Schultz as Lord Dunmore.

2. Peyton Randolph – portrayed here by Bill Weldon – talks with Williamsburg mayor John Dixon, portrayed by Steve Holloway.

To the surprise of many, Speaker Randolph and other moderates in the delegation accepted the explanation and acquiesced in the gunpowder's staying aboard the Fowey. They persuaded the people of Williamsburg to refrain from violence. It was not as easy to deflect the anger of the citizenry of surrounding counties—Patrick Henry led hundreds of armed men on a march to Williamsburg from Hanover, and they would disband only when the colony's receiver general, Robert Corbin, reimbursed them for the gunpowder, saving face for all.

Did Virginians believe Dunmore's explanation? The fear of slave insurrection was genuine in all English colonies, especially in the South, where slave numbers were greatest. In the 1760s there were risings in Loudon, Fairfax, Frederick, Stafford, and Hanover Counties, most of which involved the deaths of white overseers or owners. Though the early 1770s were relatively quiet, every white colonist knew that violence could erupt without warning.

Virginians could not fail to recall the article in the previous month's issue of a Virginia Gazette revealing a plot in the New York colony where two slaves were overheard discussing how to get their hands on gunpowder. Their plan was to set fire to the houses and stand by the doors and windows to shoot the inhabitants as they fled. "A large quantity of powder and ball was found" when the plot was discovered, said the report, and eighteen slaves were arrested.

In the week leading up to the removal of the gunpowder from Williamsburg's Magazine, there were at least six incidents of presumed slave unrest in Virginia: in Prince Edward County a slave was charged with conspiracy to commit murder, in Chesterfield County word of the possibility of insurrection caused the slave patrols to be revived, in Northumberland County a slave set fire to her master's home, in Norfolk County two slaves were sentenced to death for revolt, and in Williamsburg and in Surry County rumors that proved groundless kept the white population on edge. The growing rift between the mother country and the colonists increased the danger. Older colonists remembered Governor Robert Dinwiddie's warning during the French and Indian War, twenty years earlier: any emergency that divided white Americans could give blacks the opportunity for rebellion.

Dunmore's explanation, however, did not ring true. Virginia Gazette editor Alexander Purdie wrote June 16:

This answer gave no satisfaction. The people could not conceive how disarming them would discourage their negroes from rising, should they be so disposed; nor could they divine how he could procure the powder, upon any emergency, from a vessel whose station for one hour was uncertain. The magazine had never yet been attempted by the negroes; and, had this been apprehended, they thought it might easily have been secured by a guard. Upon the whole, they looked upon the Governour's answer as evasive and insulting; and the people were, with difficulty, kept within the bounds of moderation.Dunmore's justification was also mocked in the June 6 edition of the South Carolina Gazette.

The monstrous absurdity that the Governor can deprive the people of the necessary means of defense at a time when the colony is actually threatened with an insurrection of their slaves ...has worked up the passions of the people there almost to a frenzy.It seemed to many that Dunmore had a more sinister goal: to suppress the revolutionary movement against British rule by handing the colonists a rebellion of their own to put down and crippling their ability to contain it. It was not paranoia. A London pamphlet of the year before had argued for the emancipation of the slaves by royal proclamation and for arming them against rebels. There were rumors that an emancipation bill was about to be introduced in Parliament, although there is no evidence of it.

Richard Schumann as Patrick Henry leads Justin Chapman, left, Ken Treese, right, and the Hanover militia in a march on Williamsburg.

Extra Images:

1. Richard Schumann as Patrick Henry.

2. The following men are portraying members of the Hanover Independent Company who marched with Patrick Henry: Justin Chapman, Ken Treese, Dan Moore, Alex Morse, Adam Wright.

In a letter Dunmore wrote May 1 to his superior in London, the Earl of Dartmouth, secretary of state for the colonies, he said that rising tensions in Virginia,

particularly their having come to a resolution of raising a body of armed men in all the counties, made me think it prudent to remove some gunpowder which was in a magazine in this place where it lay exposed to any attempt that might be made to seize it, and I had reason to believe the people intended to take that step.He told Dartmouth that he tried to soothe them by saying he acted to prevent the Negroes from seizing it. He wrote that he was considering arming his own Negroes, setting free any who would join him to fight, and burning Williamsburg.

Virginians knew Dunmore had orders from London about gunpowder supplies—they had been published January 14 in the Gazette. To suffocate the flames of rebellion, the British government cut off the importation of guns and powder. The instructions told Dunmore to "take the most effectual Measures for arresting, detaining & securing any Gunpowder, or any Sort of Arms or Ammunition, which may be attempted to be imported into the Province" unless the ship bearing them had a special license from the king. This fell short of an order to seize powder and guns in colonial storehouses, but it was a small step from confiscating powder from incoming ships to confiscating it from powder magazines.

Identical instructions went to all North American governors, arriving during the winter and putting fractious colonists everywhere on notice that their gunpowder supplies would not easily be replaced. A scramble for powder would soon erupt all along the Atlantic coast.

In Massachusetts, it began before the order arrived. In September 1774, Governor Thomas Gage surprised the colonists of Somerville when his troops seized a large quantity of gunpowder, but locals in Salem were prepared when he tried five months later to snatch theirs—they removed it before the soldiers arrived. And in December of 1774, about 400 New Hampshire patriots turned the tables on the British, seizing 100 barrels of powder from Fort William and Mary.

By April of 1775, the contest was on. Gage sent soldiers April 18 to Concord to seize or destroy its gunpowder. Forewarned, the rebels hid the powder and the next day fought what became known as the Battles of Lexington and Concord. April 21, the day Governor Dunmore raided the Williamsburg Magazine, South Carolina patriots seized the powder in Charleston. The day after, Benedict Arnold—not yet a traitor—led forty men to seize the powder in New Haven, Connecticut. April 25, Maryland patriots confiscated the powder from a Baltimore storehouse.

In all but two of these actions—Gage's first seizure in Massachusetts in the fall of 1774 and Dunmore's in Williamsburg in the spring of 1775—British authorities were forestalled by patriots who, forewarned, fought or hid the powder before the soldiers arrived. Having surprise on his side contributed to the success of Gage's first raid, but with that advantage spent, the news from other colonies and from London put American patriots on notice. From then on, British efforts to seize gunpowder failed—except in Williamsburg. Why did Virginia's governor succeed while others failed?

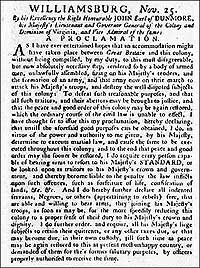

Dunmore decreed martial law in a proclamation published November 25, 1775, in a Virginia Gazette, promising to free slaves who would fight for the crown.

Dunmore had lived in Virginia three years, long enough to learn the colony's Achilles' heel. When confronted by the citizens' delegation after the Magazine raid, he threatened to "declare freedom to the slaves and reduce the City of Williamsburg to ashes" if any British official came to harm. The prospect of a British-sponsored slave uprising was more alarming to Virginians than the loss of a few barrels of gunpowder.

Believing that the best policy was to avoid provoking Dunmore, the colonists backed off their demands for the powder's return. Williamsburg's leaders were disturbed to learn that Patrick Henry and his militia were marching on the town to "help." When Dunmore heard this news, he repeated his threat: "If a large Body of People came" within thirty miles of Williamsburg, he would emancipate the slaves. Peyton Randolph wrote a letter on behalf of the city, urging the militia to stay away.

After several tense days and a good deal of dickering, the militia was reimbursed for the powder and persuaded to go home. Dunmore had won, but in the process had damaged past repair his standing among the colonial elite. Benjamin Waller, a Williamsburg lawyer and community leader, informed him that he had forfeited "the Confidence of the People not so much for having taken the Powder as for the declaration he made of raising and freeing the Slaves."

Dunmore had not been bluffing. May 1 he wrote to Dartmouth that he was confident he could "collect from among the Indians, negroes and other persons" a force sufficient to fend off the rebels. In early June, he fled the Palace with his family and continued throughout that month to try to govern the colony from the Fowey. By autumn he was raiding Hampton and Norfolk with a couple of small ships and a handful of men, many of whom were former slaves. Their victory November 14 at Kemp's Landing near Norfolk convinced Dunmore that former slaves could fight well, and he hurried to issue the emancipation proclamation he had prepared a week earlier. The document set "all indented servants, Negroes, or others (appertaining to rebels) free, that are able and willing to bear arms." November 25, the proclamation was published—and roundly condemned—in the Virginia Gazette.

To paint Dunmore as an abolitionist would be wrong. His was a quid-pro-quo emancipation. Like Abraham Lincoln almost a century later, he freed only the slaves of those who were in rebellion against the government, and Dunmore conditioned his emancipation on their service in his army, excluding from freedom women, children, and the elderly.

Why did he not free them all, as he had threatened? A general emancipation would have caused rebellious white colonists severe problems, and perhaps crippled the independence movement in the South. But it would have offended colonists loyal to the throne, many of whom owned slaves. The organized antislavery movement had not yet begun in Great Britain—it would start in the 1790s—and British merchants still profited from the slave trade. More important, a general emancipation in Virginia would have threatened British sugar plantations in the Caribbean colonies that depended upon the labor of tens of thousands of slaves.

So in November 1775, Dunmore freed some slaves—those who could escape their masters and make their way to him on their own. Estimates vary, but as many as 100,000 people are thought to have reached the British. Many were women and children, camp followers for whom Dunmore had no use, but former slaves soon made up a majority of the soldiers in his command. Diseases like smallpox killed many and battlefield injuries killed some. Others sailed with Dunmore when he left Virginia. A few ended up as free men in Canada or England.

Dunmore's proclamation encouraged black men to escape and join his army, and it caused economic hardship for the colonists. But it also helped the rebels turn neutrals like Robert "Councillor" Carter and loyalists like William Byrd III into patriots. The proclamation earned a mention in the Declaration of Independence. It is last on Jefferson's list of grievances against the king: "He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us...."

For further reading:

- Magazine

- Forced Founders by Woody Hotton

- Sylvia Frey's Water from the Rock