Page content

Spies and Scouts, Secret Writing, and Sympathetic Citizens

by Ed Crews

Drink and discretion mix badly when secrets of war are at stake. A British officer accepts a glass from a bartender eager to extract intelligence for the patriot cause. Interpreter Robin Reed is the officer, Bill Rose the colonial agent.

Thomas Knowlton's statue in Connecticut. Hale belonged to Knowlton's Rangers, which were used by Washington for spying and special operations.

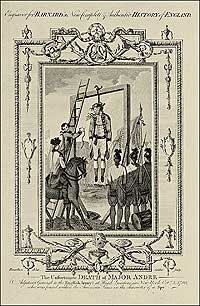

Despite objections from some of his own officers, Washington sent British spy Major John Andre to the gallows in 1780.

Methods of eighteenth-century tradecraft. In July 1777, British General William Howe sent a message, top, rolled up and inserted in the quill of a large feather, to General John Burgoyne. He would invade Pennsylvania, he wrote, rather than meet up with Burgoyne in New York.

Clements Library,

University of Michigan

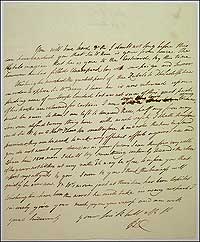

A simple method of secret writing that the Americans never caught on to. An apparently unexceptional letter from General Henry Clinton contained a secret message hidden in plain sight.

Clements Library,

University of Michigan

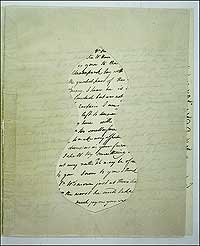

When a mask, usually posted by separate mailing, was placed over the letter, the self-contained section with the covert message was revealed.

Clements Library,

University of Michigan

The intended message, in which Clinton regrets not being able to persuade Howe to move up to New York instead of Pennsylvania: "Sr W's move just at this time / the worst he could take."

Clements Library,

University of Michigan

From left, Mark Hutter, Ron Carnegie as General Cornawallis, and Ken Treese as General O'Hara in the Colonial Williamsburg electronic field trip In the General's Secret Service.

From the Electronic Field Trip In the General's Secret Service, Edward Whitacre as Major Andre, was hanged as a spy.

United states intelligence operatives are engaged around the globe in the contest with terrorism. Others are focused on postwar Iraq and Afghanistan. Covert activities have not been undertaken on so grand a scale since World War II.

Some of these secret struggles have become public knowledge. Television viewers and newspaper readers have details of the search for Iraqi weapons of mass destruction, unconnected dots before the September 11, 2001, attacks, the capture of Saddam Hussein and Al Qaeda leaders, and the ambush and killing of Hussein's sons, Uday and Qusay.

In the string of news images, one in particular is rich in historical significance, a reminder that the American clandestine tradition is more than two centuries old. During early fighting with the Taliban, an official photograph showed American special operations soldiers riding into battle on horseback. The picture revealed the austere military environment in Afghanistan. It also provided a link to the secret side of the Revolutionary War. America's first elite, clandestine unit—Knowlton's Rangers—undertook missions for George Washington. The men photographed in Afghanistan, as well as the Army Rangers, Special Forces, Delta Force, and army intelligence, trace their origins to Knowlton's command.

Washington's Rangers are part of the larger story of intelligence operations in the War for Independence. They spanned North America, the Atlantic, Great Britain, and Europe. Engaged in the undercover war were such revolutionaries as Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, and Washington.

These men, other American leaders, their British opponents, and French allies understood that victory hinged on sound political and military intelligence. To get it, they used espionage, counterespionage, diplomatic sleight-of-hand, propaganda, scouting, partisan warfare, code making, code breaking, sabotage, bribery, deception, and disinformation.

Beginning to end, secret activities shaped the Revolution's course. British generals moved on Concord in 1775 because spies told them munitions were there. Colonial agents informed the Americans of the British plans to capture the arms and frustrated the effort. Through deception, Washington fooled the British in 1781 into thinking a Franco-American assault on New York was pending. While the British strengthened positions there and waited for an attack that never came, Washington and the Marquis de Rochambeau slipped away to Virginia, where they defeated Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown.

The methods spies use have not changed much in two centuries. Keith D. Dickson, professor of military studies at the Joint Forces Staff College in Norfolk, Virginia, says: "With the exception of technology, there are no differences. Everything familiar to intelligence professionals today was seen in the eighteenth century—double agents, secret writing, dead drops, clandestine meetings, codes, and signals."

These techniques were used in the 1700s for the same reasons they are today, Dickson said. Agents sought, and still seek, tactical information—troop movements, enemy intentions, and battle plans—and such strategic information as the goals and objectives of national leaders, their plans and policy decisions. A former intelligence officer who recently returned from military duty in Iraq as a colonel, Dickson uses Revolutionary War examples to teach strategy and related subjects to American officers.

Dickson says that then, as now, much intelligence came from nonsecret sources. "Both British and American forces depended heavily on local sources of information to gain a better picture of the enemy. Although we usually think of intelligence in terms of spies and espionage activities, most information of value to military operations during the Revolution came from what we now call open-source material: newspapers, rumors, gossip, quizzing casual observers or passers-by." These days Central Intelligence Agency analysts scan CNN and the New York Times for information.

In the 1700s, no nation had highly structured, professional intelligence organizations comparable to modern ones, according to Christopher Andrew's book Her Majesty's Secret Service: The Making of the British Intelligence Community. Spy agencies now are permanent, often large bureaucracies. They employ well-trained career officers who collect or analyze information. This institutionalized approach to secret operations began in the late nineteenth century but did not take fully its current form until the twentieth.

In the 1770s, intelligence work was more ad hoc. Great Britain had a tradition of successful—but sporadic—intelligence work beginning with the Tudors, but no permanent secret service. Even code breaking was farmed out to contractors. Clandestine activity grew during crises, and all but disappeared in peacetime. William Eden, undersecretary of state, oversaw England's spy networks in Europe during the Revolution. His budget was large, £115,900 in 1775. It reached £200,000 within three years. The sums hint at the scope of Eden's system. They also reflect the British belief in the power of bribery, used frequently and effectively, as in the case of Benedict Arnold.

The American revolutionaries had fewer funds and no clandestine tradition, a severe disadvantage, according to Edward Lengel. He's a military historian and associate editor of the Papers of George Washington at the University of Virginia and has written a military biography, General George Washington and the Birth of the American Republic, slated for publication in 2004 by Random House.

"The Americans won the war despite having an intelligence service that was almost always markedly inferior to the British. The British always had plenty of moles—loyalists by ideology or from pecuniary motive—within and outside George Washington's headquarters. Washington had no such advantage, being forced to rely for the most part on what sympathetic civilians could observe from outside the British camps."

The Continental Congress created groups to pursue covert enterprises. The Secret Committee, for instance, sought military information and aid. The Committee of Correspondence engaged in secret activities abroad. The Committee on Spies dealt with counterintelligence. They attracted such congressional talents as Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Harrison.

But the most difficult and sustained efforts were made by the Continental leaders closest to the military and diplomatic action. In 1997, the Central Intelligence Agency honored three patriots as the Founding Fathers of American intelligence: Franklin for covert action, Jay for counterintelligence, and Washington for acquisition of foreign intelligence.

Of the three, Franklin had the most experience in foreign intrigue. He had represented Georgia, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania in London before the war. There he apparently learned much. Congress acknowledged Franklin's wisdom and experience when it sent him to France in 1776. He worked in Paris to secure military aid, recognition of the American cause, and an alliance.

His diplomacy was overt and covert. He waged a public relations campaign, secured secret aid, played a role in privateering expeditions, and churned out effective and inflammatory propaganda. One coup involved distributing bogus newspaper reports of outrages committed by England's Indian allies on the frontier. Opposition members in Parliament were duped and used the material to attack the government.

Franklin's success can be measured partially by the anxiety his mission created in England. The British ambassador to Paris called him a "veteran of mischief." Franklin knew he was the object of "violent curiosities." He did all he could to keep the enemy on edge while he parried with spies curious about him.

Dickson says, "Franklin had a network of agents and friends in France who provided him excellent information on British naval force movements. On the other hand, Franklin's secretary in Paris, Edward Bancroft, was a British agent. He sent vital information written on paper in invisible ink sealed in little bottles dropped in a location for pickup by the British spymaster Paul Wentworth, who ran a very effective espionage network in Paris targeting American-French activities. Luckily for America, George III discounted most of what Bancroft provided. Franklin suspected a compromise and often sent false information out to trap the mole, but Bancroft was never discovered. Not until after his death was he discovered to be a traitor."

The French also spied on Franklin, tracking his movements as well as the movements of the British agents tracking him. In late eighteenth-century France, the government kept a sharp eye on many people—Frenchmen as well as foreigners. French agents collected diplomatic information, street gossip, and pillow talk. As a saying of the time put it: "When two Parisians talk, a third listens."

Franklin's finest achievement in duplicity came in the wake of the American victory at Saratoga. The British hoped the outcome might provide an avenue for reconciliation. The French feared it would. Franklin approached the British, pretending to open a dialog. The French found out—as Franklin anticipated—and rushed into an alliance with America, hoping to forestall a settlement.

Jay's wartime experience in secret service was less glamorous. There are few jobs in intelligence more tedious, anxious, or disheartening than catching spies. Jay brought to the work intellect, energy, and patriotic spirit. From summer 1776 to winter 1777, he oversaw the activities of a New York legislative committee charged with "detecting and defeating conspiracies." The conspiracies largely were British attempts to use Tories to control New York City. Jay's committee made arrests, conducted trials, and used agents to gather information. After the war, Jay became chief justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He also helped argue the case for approval of the federal Constitution by the states as co-author of The Federalist Papers with James Madison and Alexander Hamilton. In one piece, Jay argued that the executive branch needed the authority to conduct intelligence operations.

Washington's intelligence performance had the greatest immediate impact on Continental Army operations. Although he gained military experience in the French and Indian War, nothing had prepared him to be a spymaster, but Lengel says Washington was deeply interested in secret activities, and enjoyed dealing with agents.

"Washington was a devoted amateur," Lengel said. "He valued intelligence and used it reasonably effectively. He was also discriminating and dismissed bad intelligence more often than not. But he was still an amateur, and no match for British professionals."

Washington used scouts extensively, showed a flair for disinformation and deception, and looked for turncoats in the enemy ranks.

Lengel said Washington was not above seeking traitors in the British army, especially Hessian officers, despite his moral outrage over Arnold's defection; he was just less successful.

Washington's greatest intelligence failure involved Nathan Hale. Desperate for information in September 1776 about developments behind British lines, Washington sent Hale through them as a spy. Hale had no tradecraft and a tissue-thin cover. A manuscript found in 2003 at the Library of Congress revealed that a loyalist agent easily duped Hale into revealing his mission. Hale's arrest and execution followed quickly.

"He's still a hero," James Hutson, chief of the library's manuscript division, said late last year to reporters. "He was a brave guy who volunteered for a mission that no one else wanted to take. He was just not well-trained and didn't know quite what to do."

The CIA displays a statue of Hale at its Langley, Virginia, headquarters.

Washington had espionage and counterespionage achievements. He ran agents and networks in Philadelphia and New York. He uncovered the treachery of Benjamin Church, Continental Army medical chief, who served as a British spy. In 1776, Washington's spy John Honeyman accurately described the laxity of Hessian troops in Trenton, New Jersey, then returned and persuaded the Hessians that the Americans would not attack. The result was Washington's victory after crossing the Delaware River at night.

The capture of the British spy Major John Andre foiled Benedict Arnold's plot to betray West Point. Condemned to death, Andre went bravely to the gallows. Washington rejected pleas for clemency—some from his own officers—but not without regret.

Washington's understanding of the need for sound military intelligence is reflected in a letter he wrote to a confidant in 1777. His words still have a sense of immediacy and relevancy:

The necessity of procuring good Intelligence is apparent & need not be further urged—All that remains for me to add is, that you keep the whole matter as secret as possible. For upon Secrecy, Success depends in Most Enterprises of the kind, and for want of it, they are generally defeated, however well planned & promising a favorable issue.

Learn to decipher the CUPID code.

Learn to decipher the CUPID code."The Cupid Code" is taken from Colonial Williamsburg's Electronic Field Trip In the General's Secret Service, which will be broadcast during the 2004 - 2005 Electronic Field Trip series. For more information on registering your classroom for the live broadcast and interactive activities of this exciting interactive educational resource, visit Electronic Field Trips.

View Quicktime video clips from In the General's Secret Service Electronic Field Trip

Secret communiques are sent using a variety of methods.

The nature of espionage is deception.

Ed Crews contributed to the spring 2004 journal a story on colonial roads. Crews says readers interested in Revolutionary intelligence operations might review the relevant chapters in Spying for America: The Hidden History of U.S. Intelligence, by Nathan Miller, as well as Honorable Treachery: A History of U.S. Intelligence, Espionage, and Covert Action from the American Revolution to the CIA, by G. J. A. O'Toole.