Page content

Working Carts and Wagons

People Require Something with Wheels

by Ed Crews

Photography by Dave Doody

Online Extras

Carts Slideshow

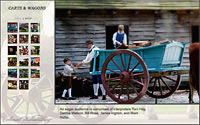

In the Historic Area version of the Williamsburg Area Transit, Dan Hard drives a stage wagon, the colonial equivalent of a bus.

Colonial Americans relied on carts and wagons much as modern Americans depend on trucks and trailers. “You have to think about how we move things today with pickups and bigger trucks,” said Richard Nicoll, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s coach and livestock director. “It was the same thing with carts and wagons in the eighteenth century.”

These simple, sturdy vehicles appeared everywhere in British North America, important to daily life and to local economies. Because carts and wagons were so commonplace and vital 200 years ago, Colonial Williamsburg uses them throughout the Historic Area.

“Our wagons and carts support interpretive programs and add a feel for everyday life,” Nicoll said. “If you would have visited the town in the eighteenth century, you would have seen these vehicles carrying all sorts of items, like firewood and produce, into town. Large loads would go to shops. If somebody was building a house, you might see mortar and bricks being hauled. When armies came through town, you’d have seen carts and wagons used to supply the troops.”

Colonial Williamsburg's fleet of working vehicles is four wagons and five carts pulled by oxen or horses. All were made through the cooperative efforts of the foundation’s wheelwrights and blacksmiths. These artisans also handle major repairs. Nicoll’s team addresses routine maintenance.

The stage wagon, the equivalent of a modern bus, carries guests along Duke of Gloucester Street. Other carts and wagons appear on side avenues or at Great Hopes Plantation, performing the tasks they did in the eighteenth century. The vehicles surface in Revolutionary City presentations as well as in films, television shows, and Colonial Williamsburg’s electronic field trips.

Such vehicles did not arrive with the first settlers. Loads in that period were lifted, pulled, pushed, carried, or dragged by humans or large domestic animals. The first vehicles in Virginia probably were simple sleds. Growth of the Jamestown colony, and the expansion of its economic activity, led to the development of roads and better transportation. For example, farmers eventually achieved grain harvests that had to go to a mill for grinding.Once a load exceeded a few sacks, pack animals or a sled would not suffice. The time came when people required something with wheels.

When the need became acute, colonists decided to use the wagons and carts they knew in England, vehicles that varied region to region. “We know what they looked like from print sources and the carts and wagons that have survived. These were built by local people, and so they had local features,” Nicoll said. “With English vehicles, you could identify where they came from by the way they looked. Their appearance conformed to either function or fashion in an area.”

Some, like two-wheeled carts, were small. Others, like hay wagons, were huge. Many vehicles were designed for special functions. Wagons that hauled barrels were designed for easy loading and unloading. Their beds could be tipped. Barrels were rolled off along an extended bed that rested on the ground.

Early Colonists tended to import wheels from England and built wagon bodies themselves. As demand grew, wheelwrights immigrated to the New World and established shops.

American vehicles began to take on their own appearance thanks to local needs and tastes. The Virginia Road Wagon appeared in the Shenandoah Valley. This reliable creation evolved into the Conestoga wagon.

The proliferation of vehicles meant the growth of roads. The first legislation on highways stemmed from the need to move farm goods around the countryside.

Most 1700s vehicles were easy to handle, and farm boys acquired driving skills early in life. “Driving a wagon or a cart was a common skill for farmers,” Darin Tschopp said. He works with Colonial Williamsburg’s ox teams. “They learned it as they grew up. On a middling farm, the men would load the cart in the fields, and the kids would drive it back to the barn. Most likely, women knew how to handle a cart, too, because you needed everybody to work at harvesttime.”

Tschopp said that driving carts and wagons is so simple twenty-first century Americans can get the knack for it quickly. “They’re a lot like a pickup. The ‘engines’ are up front, and the payload is in back. You have limits on how much you can carry.”

In some ways, carts have advantages over trucks because they only have two wheels. This allows for a sharper turning radius, which can be handy in tight spaces.

Of course, there are differences. A cart driver has to remember that wheel hubs protrude beyond the wheel rim. That becomes important in narrow spots, and a moment of inattention can result in a wrecked fence or worse. A driver must keep a wagon’s length in mind, just as the operator of a modern eighteen-wheeler does. Tschopp also said that, unlike an automotive engine, draft animals get tired. So the work pace and the loads become elements in planning a job. Anybody handling a wagon or cart must become attuned to its sounds. Odd noises may signal that something is loose or is not fitting correctly.

Like Nicoll, Tschopp said the presence of eighteenth-century vehicles helps guests visualize colonial life and understand how work got done. Guests ask questions about their construction and function, and what it is like to work with draft animals.

Tschopp is quick to say that driving these vehicles is fun. So is seeing guest reaction.

“Our guests encounter lots of horses, especially with carriages,” he said. “So I like showing oxen and carts. It’s a nice visual image for the Historic Area.”

Ed Crews,, a Richmond-based writer, wrote the preceding gambling story and contributed to the summer 2009 journal an article on colonial chickens.

Suggestions for further reading: