Page content

The Alternative of Williams-Burg

"Monster madness... the Patriots are in high Spirits just now."

by Robert Doares

A slurry brew of pain and public mortification, tar and feathers was the punishment for unrepentant Loyalists in the 1760s and '70s. Standing, from left, Tom Hay, Donna Wolf, Don Kline, Robert Brown, and Christina Lane. Dan Moore is the sticky victim.

Extras: Additional images of the tarring, the victim, and behind the scenes as Abigail Schumann applies molasses "tar" and feathers to Dan Moore.

IN THE AUTUMN, Colonial Williamsburg interpreters re-enact the town's most notorious instance of revolutionary vigilantism, the raising of the Liberty Pole in front of King's Arms Tavern on Duke of Gloucester Street in late 1774. In other colonies, residents had already hung flags on poles or trees as places where Sons of Liberty could rally at the least affront to patriot sensibilities. Often, a barrel of tar and bag of feathers were kept nearby as reminders of the consequences of non-compliance with public resistance to British authority. No loyalist or British official in Williamsburg ever suffered the pain, disfigurement, and humiliation of the coat of tar and feathers visited on Boston customs man John Malcomb in January 1774. Yet, such a thing almost happened in Virginia's capital in November that year. Though there was no violence in Williamsburg, the affair set the town—and the mother country—abuzz.

Between the time of American reaction against the Stamp Act of 1765 and the first shots of the Revolution at Lexington and Concord in 1775, Virginia annoyed the British government far less than Massachusetts. Trouble followed trouble in Boston, prompting parliamentary retaliation and indignities that engendered even the sympathy of those who once thought Massachusetts reaped what she sowed. When news of British punitive reaction to the Boston Tea Party of December 16, 1773, reached Williamsburg in January 1774, few Virginians could continue sanguine about Massachusetts's woes. The Virginia burgesses staged a colony-wide Day of Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer on June 1, 1774, the date the British Navy closed the port of Boston in retribution for the nighttime destruction of East India tea by Bostonians mummering as Indians. A letter written on Virginia's day of protest by a Williamsburg lady to a London friend appeared in an English newspaper:

Never since my Residence in Virginia have I ever seen so large a Congregation as was this Day assembled to hear Divine Service. What will be the event God knows ...We expect there will be a Stop put to Importation and Exportation, which may fall heavy on England, as she depends chiefly on her Trade. America has every thing within herself that is necessary and convenient ...and can do much better without England, than England can without her.In August, Virginia's elected representatives, meeting in convention, formalized an association to curtail trade with Britain. The next month, Virginians made their case for the boycott—a word at the time uncoined—at a Continental Congress of all the colonies in Philadelphia. Congress mandated elections for local committees of safety to enforce the Continental Association's moratorium on imports after December 1. The committees intimidated merchants who hesitated to sign an agreement that so impinged on their livelihood. Shopkeepers suspected of violating the Association were subjected to searches of their premises and examination of their records. Offenders faced a range of reprisals. A blistering coat of hot tar and feathers—a sometimes-fatal remedy Americans employed during tax protests of the 1760s—was among the worst. In Virginia, William Smith of Portsmouth had been tarred, feathered, and nearly drowned in April 1766.

On November 27, 1774, Norfolk merchant James Parker, a loyalist, wrote to his colleague Charles Steuart in London, "I would willingly hope the Patriotic fever here is at the hight as we have lately had some of the most extravagant proceedings you have heard of." For a time, Parker put off the Norfolk Committee of Safety's demand that he sign the Association. He said he had "a small post, Deputy PM ...and had taken the Oath of Allegiance to his Majesty, therefore could not consent to do any thing that had the least appearance of perjury or ingratitude." By PM, he meant postmaster.

The turn of events alarmed American loyalists and tarnished Virginia's image in the British press.

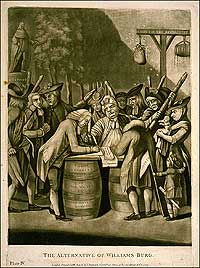

In a print from London, The Alternative of Williams-Burg, the mother country barbed the ingrate American rebels for their coercion and violence against Loyalists.

IN FEBRUARY 1775, the London publisher Robert Sayer & J. Bennett gave Virginia a black eye by printing a mezzotint satire, The Alternative of Williams-Burg, attributed to the printmaker Philip Dawe, a copy of which is preserved in the collections of Colonial Williamsburg. It depicts Virginia merchants forced to sign the Association. In the upper left corner, the statue of late Virginia Governor Botetourt intimates the Capitol courtyard in Williamsburg. For a desk on which to write, patriots have laid a plank across two tobacco barrels. One is labeled as a gift for John Wilkes, newly elected Lord Mayor of London, who campaigned on a platform of sympathy with the colonial cause. Some of the gentlemen merchants appear loath to conform, but a liberty pole sporting a barrel of tar, bag of feathers, and the inscription "A CURE FOR THE REFRACTORY" suggests the alternative. The image is similar in composition and tone to the engraving of John Malcomb's tarring and feathering that Sayer & Bennett issued in October 1774.

The Alternative of Williams-Burg captures the turbulence of the second week of November, which began with Virginia's own tea party November 7 at Yorktown. Citizens of the port assembled that Monday and boarded the ship Virginia at ten o'clock after learning it contained two half chests of tea imported by John Hatley Norton, Yorktown agent of John Norton and Sons of London, for merchant John Prentis of Williamsburg. The men waited all morning for word from a committee of burgesses at Williamsburg—probably Peyton Randolph, speaker of the house; Robert Carter Nicholas, treasurer of Virginia; and Dudley Digges—who were deliberating the matter. When members of the Gloucester County committee arrived just after noon, they found that the "Tea had met with its deserved fate," the men of York having hoist it from the ship's hold and cast it into the river. Parker wrote that the committees "intended to have burnt the Ship, but that could not be done where the Ship lay." Instead, it was "ordered that the Ship should not be permitted to take in any Tobacco, but sail from this Country in 14 days in ballast." By which they meant empty of a return cargo, to the loss of its owners. Parker identified gentlemen Thomas Nelson Jr. and Captain Thomas Lillie as the "most active" Yorktown instigators.

The York and Gloucester County committees passed resolutions condemning Norton, Prentis, and ship's Captain Howard Esten for violating the Virginia boycott, which began November 1, a month before the Continental Association. The committees published their resolutions in the Williamsburg newspapers—there were two—of November 24, and Prentis's printed apology followed:

It gives me much Concern to find that I have incurred the Displeasure of the York and Gloucester Committees, and thereby of the Publick in general, for my Omission in not countermanding the Order which I sent to Mr. Norton for two Half Chests of Tea; and do with Truth declare, that I had not the least Intention to give Offence, nor did I mean an Opposition to any Measure for the publick Good. My Countrymen, therefore, it is earnestly hoped, will readily forgive me for an Act which may be interpreted so much to my Discredit; and I again make this publick Declaration, that I had not the least Design to act contrary to those Principles which ought to govern every Individual who has a just Regard for the Rights and Liberties of America.

Holding a barrel of tar, Bill Rose churns up the crowd. In Williamsburg, Patriot sentiment ran toward punishing anyone who opposed the boycott of tea and other British goods.

A letter of January 5, 1775, from the elder John Norton in London, published that May in a Virginia Gazette, apologized for the confusion over the Prentis tea and the dates for the Association. The letter said that Captain Esten—long admired and trusted by Virginians—had complied with Norton's instructions in reporting the tea to authorities at Yorktown upon landing. Norton concluded with hopes "that the imputation of injustice to America will cease" and that his company would "recover that place which they formerly held in the esteem of their friends and countrymen in Virginia."

NEWS OF THE YORKTOWN TEA PARTY circulated in Williamsburg as nearly five hundred merchants arrived in the capital for a meeting on that Wednesday, November 9, where they were expected to sign the Continental Association. Most complied, and Randolph and other Virginia delegates to Congress gathered at the Capitol to accept the document. The effect of the incident at Yorktown, combined with the reluctance of some merchants to sign, prompted the event represented by The Alternative of Williams-Burg. Parker wrote to Steuart: "At Wmsbg there was a Pole erected by Order of Col. Archd. Cary, a strong Patriot, opposite the Raleigh tavern upon which was hung a large mop & a bag of feathers, under it a bbl of tar." By "bbl" he meant barrel.

If Patrick Henry's short fuse helped fix his prominence in the Revolution in Virginia, one wonders why irascibility didn't do the same for patriot Archibald Cary, who erected Williamsburg's Liberty Pole. Though considered to be in the camp of conservative patriots like Speaker Randolph and Treasurer Nicholas, Cary's bulldog temperament kept him at the center of matters of revolutionary import. At least as outspoken as Henry, Cary's name appears in the journals of the House of Burgesses with ten times the frequency of Henry's or Jefferson's. No stranger to controversy, he is remembered in Baptist histories as a persecutor of that denomination in his own county of Chesterfield, where as chief magistrate he imprisoned itinerant ministers in 1772 and 1773. When one of these persisted in sermonizing from the window of the jail, Cary, it is said, erected a high enclosure to block the view between preacher and flock.

Henry is remembered for decrying the government of George III. Cary, on one occasion, decried Henry. As speaker of the Senate in the 1776 first session of Virginia's revolutionary legislature, Cary may have thwarted a movement to declare then-Governor Henry a Roman-style dictator of the new Commonwealth. Henry may not have known of the plan, but tradition says Cary accosted the governor's step-brother in the House of Delegates and said: "I am told your brother wishes to be Dictator; tell him that the day of his appointment shall be the day of his death—for he shall feel my dagger in his heart before the sunset of that day."

An unpopular Boston customs commissioner, John Malcomb, is entertained by Patriots. A rope around his neck, accursed British tea down his throat, and a bit of tar and feather to garnish.

PARKER WAS NOT IN WILLIAMSBURG when Cary raised the Liberty Pole, but he learned of it from other Norfolk merchants, among them his brother-in-law and business partner, William Aitchison. In a November 14 letter to Parker, Aitchison wrote that every method had been used to get everyone to sign the Association. "A large tar mop was erected near the Capitol wt. a Bag of feathers to it and a Barrl of Tar underneath—Severall People were called before the Committee and obliged to make any unguarded aspersions they had used."

Two such unfortunates were Southside merchants Anthony Warwick and Michael Wallace of Milner's Crossroads in Nansemond County, whom the Norfolk Committee of Safety had reported for having "imported a little tea" for a store in North Carolina. Word of this got to Williamsburg by the time Warwick and Wallace arrived for a meeting of the merchants, a regular gathering of men participating in trade. Though Williamsburg would not elect its Committee of Safety until December, what Parker called an "Occasional Committee" chaired by Cary assembled to consider their case. Warwick and Wallace were "Complained of & a very insolent and formal Charge wrote out against them," Parker said. A committee member, "Young Nicholas (the Comptroller to be) spoke very violently against them & asked how they durst insult the Majesty of the People."

Parker's letter implies that the men were nearly tarred and feathered. "It was intended to have used them very ill," he wrote, "but the Treasurer, Speaker, Mr. Pendleton, and some others interfered." Pendleton was Edmund Pendleton, who would become leader of the Committee of Safety. Another cool head, Colonel Robert Munford, addressed Cary's committee, saying that "such proceedings was more arbitrary then any the Americans were complaining of & tended to destroying their Cause." Munford suggested that Warwick and Wallace had done nothing to violate the Continental Association, which allowed them "to import as usual till the first of Decemr." The committee ordered the two merchants to retrieve the tea from North Carolina and to deliver it to the Committee of Safety in Nansemond, and "here the matter ended."

Aitchison wrote to Parker:

I am really glad you were not there ...there was a complaint lodged with the Committee against you for some words spoken here, and had you been upon the spot there is little doubt but you would have been as roughly handled as any of 'em. I beg you to be more upon your guard for the future. There is no contending with such Numbers.

Another view of Malcomb's punishment. Again, tea, the gallows, and generous daubs of tar and feathers. The hat's 45 alludes to John Wilkes's attack on the king in the North Briton No. 45.

THE INCIDENT on Duke of Gloucester Street, which came so close to physical abuse, unnerved gentlemen who had come to Williamsburg on personal and public business. Parker wrote that when townspeople got word that many of the gentlemen were planning to leave the capital—a blow to the commerce of the season—they "removed the tar & feathers & Cary was generally blamed." Nevertheless, after all the "preaching up the terrible consequences of refusal ...the Association was signed by almost everybody." A report of the Nansemond committee published December 1 said Warwick and Wallace "this day voluntarily signed the association agreed to by the general congress, and declared they were well pleased therewith ...and seemed sorry that their intentions should be misconstrued, as they never did intend to secret the said tea."

Though he escaped unscathed in Williamsburg that November 1774, Warwick was less fortunate in August 1775, when he was taken up in Smithfield by citizens of Isle of Wight County on suspicion of violating the Association. The Virginia Gazette reported his treatment, our best description of a Virginia tarring and feathering:

The populace very deliberately led him to the stocks, and having prepared him for the purpose, gave him a fashionable suit of tar and feathers, being the most proper badge of distinction for men of his complexion. They then mounted him on his horse, and drove him out of town, through a shower of eggs, the smell of which our correspondent informs us, seemed to have a material effect upon the delicate constitution of the motleyed gentleman. At parting, the gentmen gave Mr. Warwick a friendly piece of advice, which it is hoped he will observe, if only for the sake of his own interest.Parker continued his commentary on the Williamsburg disturbances in his next letter to Steuart on December 6. In response to some remark by Steuart about hope for mediation by moderates among the burgesses, Parker said: "You are mistaken in Mr. Pendletons moderation." He said at Williamsburg it was not of consequence whether the merchants signed the Association or not, because the Congressional delegates were the representatives of the whole and what they did in Congress "bound the whole, but if anyone refused he should be delivered over to the People, in this sentiment he was joined by" Richard Bland, an early espouser of the doctrines that led to independence.

I would send you some newspapers but they are all now on one Side, they have scared the Norfolk printer so that he will only write what is agreeable to them. The Wmsbg. papers if possible is worse... I do not know how long this Monster madness will last but the Patriots are in high Spirits just now.Despite the turmoil of the fall of 1774, Parker clung to a bit of optimism in his last letter of the year to Steuart. December 28, he wrote:

I should be as sorrie as you to See the Constitutional authority of Government over America given up, it is not for our intent it Should, & if the Colonies prevail (of which I cannot entertain the least Idea) Insolence, Contempt, & Confusion will long predominate here ...I am still of the opinion, notwithstanding all the noise of arming, & mustering, the Colonists never will attempt fighting.

Robert Doares, an instructor in Colonial Williamsburg's department of interpretive training, contributed to the Christmas journal an article about religion and the colonial holiday.