Page content

The Town of the Nativity

Columbus' Christmas City

by Dennis Montgomery

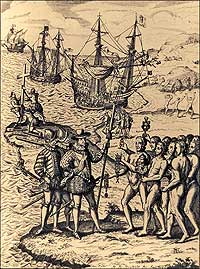

Columbus left thirty-nine of his crew behind after foundering off Hispaniola on Christmas Day, 1492. When he returned a year later, the fort and settlement of Navidad those sailors built had been burned to the ground and all thirty-nine were dead.

The ships of Columbus's fleet, the Niña, the Pinta, the Santa Maria, struggle toward the New World in this nineteenth-century print.

On Christmas Day, 1492, misfortune and poor seamanship shipwrecked Christopher Columbus long enough for him to found Villa de Navidad—the Town of the Nativity—a palisaded, moated enclosure on Haiti's coast. He, a few historians, and one or two journalists have been pleased to call it the first European city in America. Some say not a city, not even a town, but a settlement. Others just call it a disaster. By anyone's lights, Columbus may as well not have bothered.

La Navidad, as it is commonly called, was too small a place to support the dignity of a noun grander than fort, and though, by any name, it was the first Spanish outpost in the New World, the Vikings had set up the hemisphere's original European settlements centuries before. Just as Jamestown's claims to primacy are fenced with qualifiers—the first permanent English settlement in America—so must the pretensions of La Navidad be confined to the limits of Hispanic enterprise.

Nevertheless, the Town of the Nativity deserves notice as an early American bastion of Europe's version of civilization. It was the archetypal New World base of Spanish rapacity, an enclave established by the navigator upon whom King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella bestowed the title Admiral of the Ocean Sea, and who yet is popularly credited with the discovery of the New World.

The honor of finding the Americas, of course, had been taken 20,000 or 30,000 years before by ancestors of the millions of Native Americans who populated them by the time Columbus arrived. You might say, as an old bumper sticker did, that the people Columbus called Indians discovered him. Not the other way around.

The admiral's knowledge of the achievements of the Norsemen and the naturals, however, was limited to myth and conjecture. He was, more or less, lost—he thought he had reached the Indies, as Asia was called—and, as I say, he was shipwrecked. So it is ungenerous to fault a man who did not know where he was for claiming credit he did not know that he did not deserve. The admiral had his pride.

Christmas Eve, Columbus, aboard the Santa Maria, in consort with La Niña—the Pinta had run off to try to beat the rest of the fleet to New World gold—was coasting eastwise on modern Haiti's north shore, just past today's Cap Haitien. The Spanish called this island Hispaniola or Española. The better part of it now is the Dominican Republic.

The admiral and his sailors were recovering from a marathon holiday party thrown for them at a Taíno Indian village in their wake. As historian Arthur Davies put it, "All the ships' crew had spent three days carousing with Indians and their women." To be fair, Columbus went ashore because he thought Hispaniola was Japan and wanted to have a gander at the land of the rising sun. Particularly, he wanted a look at the gold-roofed palaces and pagagodas about which Marco Polo and John Mandeville had written in their travelers' tales. The Spanish were mad for gold.

Now they were on their way to another native village, the headquarters of the young cacique, or chief, Guacanagarí to attend a bigger, better Nativity bash. Everyone was tired. Columbus said he had not slept in two days. The night was calm, the sea was smooth, a moon was up, and, at about 11 p.m., the admiral repaired to his berth for some shut-eye.

He left the helm in hands of a sailor, also ready for a nap, who turned the tiller over to a ship's boy —or a gromet as they are called—and bedded down, too. There was at the bow no watch, and from his station in steerage the gromet couldn't see where he was going. Driven by the current, at midnight the lad steered Columbus's flagship aground. Awakened, the admiral ordered the vessel's master to get in the ship's boat and carry the stern anchor back the way they came. The idea was to drop it, wind its cable around Santa Maria's windlass, and try to kedge her off. Instead, the oarsmen pulled for La Niña. La Niña's captain drove them away, thinking the master's crew cowards and deserters, though they may just have been looking for his help. At all events, by the time the boat, along with one from La Niña, got back to Santa Maria, the flagship had swung side on the reef, stuck fast, and was rolling on her beam ends. Hoping the tide might float her off, Columbus lightened load, casting off cargo and cutting down the mainmast. It was no use.

Juan de la Cosa sailed with Columbus and made this chart of the Western Hemisphere, Europe sideways at the bottom, ca. 1500.

At daybreak, the admiral put two other men in the boat and sent them to Guacanagarí—Santa Maria had almost reached the cacique's village—to relate the ship's misfortune. Columbus said Guacanagarí "wept when he heard the news, and sent all of his people with large canoes to unload the ship. This was done, and they landed all there was between decks in a very short time, such was the promptitude of that king." Sixteenth-century chronicler Peter Martyr, who later met Columbus, wrote: These people also brought off the men from the wrecked ship, as well as all it contained, transporting everything in barques which they called canoes. They did this with as much alacrity and joy as though they were saving their own relatives; and certainly amongst ourselves greater charity could not have been displayed.

Guacanagarí turned his home, and others', into storehouses for Columbus's trading truck and supplies.

The Spanish were safe, but in a jam. There was not room enough for everyone aboard La Niña for the trip home. Some folks would have to stay. Guacanagarí said they were welcome to live in his village, and that his tribe for their comfort would help them build their own place.

December 26, Columbus ordered a palisade and a watchtower raised, and a moat and a cellar dug. For lumber and hardware, Spaniards and Indians joined to strip the flagship. Ten days later, the work was enough in a state of forwardness to justify Columbus's departure.

Sometimes an optimist, and always a mystic, Columbus looked on the bright side. He said he "knew that our Lord had caused the ship to be stopped here, that a settlement might be formed ...in truth, the disaster was really a piece of good fortune." He laid this stroke of luck on the backs of thirty-nine unfortunates—among them three lieutenants, a caulker, a carpenter, a gunner, and a cooper—gave them the ship's boat, a cannon, seeds, and more than a year's worth of wine and food. According to the admiral, men begged to stay behind to collect gold. As I said, the Spanish were mad for gold. Guacanagarí said he would look after them.

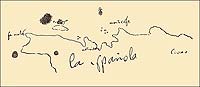

Believed to be by Columbus's own hand, this map sketched the island of Hispaniola, with Navidad marked on the north shore. The Granger Collection, New York

Columbus told the castaways not to bother the Indians, especially the women, to stay together, to stay home, not to steal, to be virtuous, to mind their commanders, to gather treasure, and, when it was convenient, to take the boat and look for a gold mine down the coast that they had heard about. That was one of the things the cellar was for, for gold and treasure. Columbus persuaded himself that his men were in no danger because the natives—who, he mentioned every time he had the chance, "all went as naked as when their mothers bore them"—were timorous and too ill armed to annoy the Spanish.

At sunrise January 4, he weighed anchor, and sailed off in the general direction of the Iberian Peninsula, pausing to show the Indians what gunpowder and a cannon could do by blowing a stone ball through Santa Maria's hulk.

Weeks later as he neared the shores of Portugal, the admiral unlimbered his pen and wrote a letter home to Spain's queen:

I have taken possession of a large town, to which I have given the name Villa de Navidad, and in it I have made fortifications and a fort, which now will be by this time entirely finished, and I have left in it sufficient men for such a purpose with arms and artillery ...and a great friendship with the king of that land, so much so that he was proud to call me, and treat me, as a brother. And even if he were to change his attitude to one of hostility towards these men, he and his do not know what arms are ...so that the men whom I left there alone would suffice to destroy all that land, and the island is without danger for their persons, if they know how to govern themselves.

They did not.

It would be eleven months, until November 27, 1493, before Columbus came back to see how the thirty-nine were getting along. They had improved their time by hunting not only for riches but, despite the admiral's admonitions, for feminine favors. One took three women for his bed; another four; and ten others, five.

A group wandered off to look for gold works; another group took its leisure at home. They bickered murderously, and split into predatory gangs that scouted for plunder and women. They were the kind of seamen who give sailors a bad name.

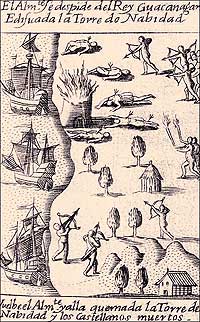

The Indians—Guacanagarí said they were stirred up by two other neighborhood chiefs—thought the Spaniards' insolence poor recompense for his hospitality, took umbrage at the intruders' deportment, and fell on them. Some from the fort they chased into the woods and cut off; others they ran into the sea to drown. They attacked the gold mine expedition, too. Some Spaniards saved them the trouble of murder by dying of disease.

When Columbus returned and stepped ashore, all thirty-nine were corpses. He and his current companions first found four bound bodies decomposing near a river, and eleven more at La Navidad, grass growing over them where they fell. The new arrivals fired guns and cannon to signal to any countrymen who might be hiding in the woods. No one came out.

The fort was burnt, and Spanish clothing and possessions were strewn about. European goods had found their ways into Indian homes. Columbus ordered the fort's cellar dug, discovered a disappointment of his hopes, mustered a platoon of uniformed men under arms, marched them off to Guacanagarí under pipe and drum, and started asking for explanations.

Bit by bit, Guacanagarí filled him in, absolving himself of blame. Faking a leg wound, the cacique tried to persuade the Spanish that he had fought beside the La Navidadans. The ruse was discovered. Suspicious Spaniards proposed executing the cacique on the spot, or arresting him, but Columbus dithered over the evidence and worried about further offending the aboriginals, and Guacanagarí escaped revenge. Just as well, too, because it turned out that a cacique named Caonabo bore most of the blame for the homicides.

The admiral, perhaps feeling guilty for having put the thirty-nine in such a precarious position, came to blame the castaways, instead of himself or the Taínos, for their deaths:

For these Indians are not a people, unless they were to find us sleeping, to undertake anything, even if they had the thought. So they did to the others, who remained here, owing to their lack of care, for few as they were and for all the occasions of which they gave to the Indians to have and to do that which they did do, they would never have dared to attempt to injure them, if they had seen that they were watchful.

Four hundred and fifty years later, Columbus biographer and scholar Samuel Eliot Morison wrote:

The causes of this disastrous finish have not been determined completely by the historians. To the differences and rivalries and lack of discipline which prevailed among them, and to their desertion of the fort of Navidad in favor of roaming freely over the island, one has to add their disobedience to one of the concrete recommendations of the discoverer: that of not abusing any Indian, "especially the women." Impartial historians must come to the conclusion that this last was one of the most important reasons for the death of the garrison left in the fortress of Navidad. A good part of them very soon grew tired of the monotonous guard duty in the fort, and preferred to dally with the Indian women.

That's nearly the end of the story of the first Spanish settlement in the New World. Columbus had never cared much for the makeshift site of La Navidad, and he ordered construction of a capital at a place he named La Isabella. He understood it was nearer that gold mine. It would be the scene of greater horrifics, though the Indians would be the victims now.

Isabella, like La Navidad, would be abandoned and drop from sight. In the 1980s, archaeologists may have discovered La Navidad's remains at what is now En Bas Saline. But historian Davies had written La Navidad's epilogue in 1953:

The massacre of the garrison at Navidad was in some respects the critical fact in the history of the West Indies. Queen Isabella had insisted that the Indians were to be treated kindly and converted for Christianity, but after the massacre the Spaniards and Columbus oppressed them mercilessly. Within a generation, 300,000 Indians of Hispaniola had been enslaved or had died in terrible conditions, and had almost been wiped out.

Dennis Montgomery contributed to the winter 2007 journal a Jamestown story.