Page content

Milking Devons

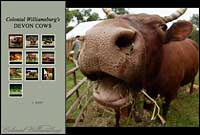

Picture Perfect Cattle for Colonial Williamsburg

by Ed Crews

Photos by Dave Doody

Elaine Shirley, manager of Colonial Williamsburg's rare breeds program, helped keep Milking Devons from disappearing.

American Milking Devon Cattle nearly vanished from the planet. Cows of an antique and once-popular stock, by the 1970s, the world's population of the animals had dwindled to less than 100. Just when the decline looked irreversible, individuals and organizations set out to save them, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and its coach and livestock staff among them.

It was during the early 1980s that the foundation decided to try to help save threatened domesticated breeds. In 1986, it selected Milking Devons as the first animals for its rare breeds program. Seventeen Devons live now contentedly at Colonial Williamsburg, and the global herd numbers 600.

Elaine Shirley, rare breeds program manager, seems to have in her heart a soft spot for Devons. She likes their gentle nature, their versatility as farm animals, and their appearance—sometimes she'll look at them standing in a pasture and call it a living work of art. She is proud of the foundation's role in saving them from extinction.

Devons are historically correct. The first cattle imported from Devonshire, England, arrived in Massachusetts during 1623. Records from the 1700s mention red cows being raised in Virginia, and the Devons certainly are red, their coloring ranging from deep mahogany to chestnut.

They are calm, friendly, intelligent, hard working, and hardy. Devons can do well on a low-quality, high-forage diet, and they are relatively unaffected by harsh climates, traits that help explain their centuries-old popularity in New England. They are adaptable, too. Today, they do well in places as diverse as Oklahoma, Georgia, and New Mexico.

Colonists and later Americans admired the Devons for all their characteristics, and because they made good draft animals, could provide adequate amounts of milk and meat, and their milk could be turned into fine dairy products.

Devons tend to be healthy with good lifespans. As modern cattle go, they are not extremely large. Cows typically weigh from 1,000 to 1,200 pounds; bulls from 1,600 to 1,800 pounds. At birth, calves usually are between 75 and 100 pounds.

Colonial Williamsburg interpreter Carrie MacDougal brushes a red Milking Devon, with Ian MacDougal, Rachel Harcourt, and Martin Harcourt in the background. In addition to producing milk and meat for colonists, the Devons were good draft animals.

"We always have cattle of some sort in town," Shirley said. "People like seeing them around. Interpreters can use the animals to give a talk on eighteenth-century farming practices, and we even milk cows in front of people in town. Visitors often are amazed at how people-oriented cattle can get."

Interpreters remind guests that early Americans knew nothing of selective breeding as practiced today. Colonial farmers did not relentlessly breed animals for specific qualities or purposes. For them, multipurpose cows were fine.

In the nineteenth century, selective breeding began in earnest, leading to Beef Devons and Milking Devons. The cattle were admired as draft animals, particularly in difficult conditions, as Lewis F. Allen noted in the 1800s:

For active handy labor on the farm or highway, under the careful hand of one who likes and properly tends him, the Devon is everything that is required in an ox, in docility, intelligence, and readiness for any task demanded of him. Their activity in movement, particularly on rough hilly grounds, give them for farm labor almost equal value to the horse, with easier keep, cheaper food and less care. For his lack of size the Devon is not so strong as other breeds, but "for his inches," no horned beast can outwork him.

But when the internal combustion engines started providing power for tractors, trucks, and other equipment, few farmers wanted Devons for draft work, and other breeds did much better as dairy and beef cattle. Early in the twentieth century, Devons began a long, slow slide toward oblivion.

In 1952, a small group of breeders tried to keep Devons as dairy cattle, and to maintain stock for draft duties and meat. The effort was not notably successful, but the Devons' future got brighter during the American Bicentennial. Historical sites became interested in trying to find animals that resembled as closely as possible those from early years. This spurred interest in protecting breeds that provided living links to the past. Colonial Williamsburg decided to find some Milking Devons. They would be picture-perfect for Historic Area pastures.

Interpreters Carrie MacDougal and Eric Hunt talk about the history of the Devons, as well as the rare breeds program, to guests in the Historic Area: the Savercool family from New Jersey, the Tombros from New York, and Michael and Sally Woodard from Florida.

Colonial Williamsburg also knew that Devons were popular in New England. That region seemed like the best place to start looking.

"We discovered some Devons in Alton, New Hampshire. The owner was Mrs. Alice Ziegra. She had Devon cattle and was prominent in the Devon cattle association. Her sons were into raising oxen and had a herd. She agreed to help. She was a widow and was downsizing her herd. So she sent us Nora, an adult female," Shirley said.

Soon the foundation began breeding Milking Devons, initially through artificial insemination. Later, it acquired a bull.

"We have sold and traded offsprings with others to expand the breed," Shirley said. "We've sold animals in New England, Virginia, and elsewhere in the South. We've sold animals to various organizations and brought in animals to vary the gene pool."

The number of Milking Devons is growing, and the breed's future looks brighter every year. For Shirley, the importance of her work was brought home when she encountered some English guests in Williamsburg. The meeting reminded her just how fragile some domestic breeds are, and what a difference a rare breeds program can make.

"The lady said to me that she wished she had a Milking Devon," Shirley said, "but, of course, she didn't because basically the breed has died out in England, its original home."

Ed Crews, a Richmond-based writer, contributed to the autumn 2007 journal a story about Colonial Williamsburg's riding chairs.

Suggestions for further reading