Page content

Bogged Down in Cranberries

by Mary Miley Theobald

Cranberries being harvested in Richmond, British Columbia. Bogs are flooded and the berries shaken loose, which float to the surface and are skimmed off. Nearly all the world's production of cranberries is from Canada and the United States.

A cranberry blossom, thought to resemble the head and bill of a crane. The berry got its name from that likeness.

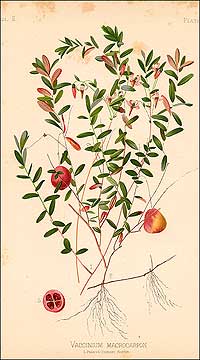

A mid-nineteenth-century lithograph of a cranberry bush by Louis Prang after Alois Lunzer in a book on native flowers and plants.

A water-reel harvester at the Rutgers University Blueberry and Cranberry Research Center in Chatsworth, New Jersey.

Like the turkey at Thanksgiving and Christmastime, jellied cranberries have become a traditional part of holiday meals.

Sometime after the Pilgrims landed in Massachusetts, they learned from the Pequot Indians of an edible berry called ibimi, or "bitter berry." The Indians mixed these berries with dried venison and fat to make pemmican, a long-lasting, portable fast food for hunting trips or trade expeditions. Ibimi berries are red, and the juice worked nicely as a red dye. They served, too, for a poultice for healing wounds because, raw, they have an astringent effect that reduces bleeding. The story goes that the Pilgrims, who had never seen such a fruit, were struck by the ibimi flower's resemblance to the head and bill of a sandhill crane and so named them crane-berries. This, however, sounds suspiciously like one of those Parson Weems fables about chopping down cherry trees—charming but fictional.

Truth is, a smaller version of the American cranberry grows wild in the bogs and marshes of England, northern Europe, and Siberia, so an unfamiliar plant would not likely have confounded the Pilgrims. In England, the small berry version, Vaccinium oxycoccos, goes by such names as marsh-berry, bog berry, and fen whort, none predominating. In the language known as Low German, it is called the kranebeere, meaning crane-berry. In the event that the Pilgrims were unacquainted with the fruit in England, they surely encountered it during the eleven years they lived in the Netherlands, then the trading center of the world, where the berry grew wild in marshy patches.

They certainly encountered the Low German language. Low German has much in common with Old English. It had been the lingua franca of the medieval Hanseatic Trading League of northern Europe that was still operating in the 1600s, and it was widely spoken along the reaches of the lower Rhine River and the eastern Netherlands, where the Pilgrims lived. It seems far more likely that the Pilgrims used the Low German word that sounds the same in English, krane, for the fruit that they were familiar with from Europe.

In short, the berries may have been named for their resemblance to the crane, but it was the Germans, not the Pilgrims, who noticed the resemblance and applied the word to the European berry.

The American cranberry, Vaccinium macrocarpon, is indigenous to the acidic bogs and wetlands of the northeastern United States and southern Canada. There's a little-noticed wild cranberry bog at Colonial Williamsburg's Carter's Grove.

The wild fruit was not cultivated until the nineteenth century. Like the blueberry and the Concord grape, these bright red berries were adopted by European settlers and adapted for sauces, jellies, preserves, and tarts. No reason an English recipe for gooseberry tarts would not do just as well with American blueberries or cranberries. Soon, ships embarking from New England ports carried cranberries to prevent scurvy, just as ships leaving tropical ports carried limes. Happily, for the sailors, fresh cranberries come naturally coated with a waxy substance that acts as a preservative, keeping them fresh for weeks—some say up to five months.

These large New England cranberries were exported to England sometime before 1686, and soon the German-American name came to represent the large and the small species. A survey of cookbooks published in England during the eighteenth century turns up cranberries. Elizabeth Raffald's The Experienced English Housekeeper, published in 1769, gives these directions for preserving them: "Get your cranberries when they are quite dry, put them into dry clear bottles, cork them up close and set them in a dry cool place." John Farley uses almost the same words in his London Art of Cookery, published thirty-eight years later. Prepared this way, they could be used to "garnish your dishes all the Winter."

Most cranberries were made into sauces, preserves, or tarts. To counteract the bitterness, cooks used sugar, maple syrup, honey, or whatever sweetener was available. In American Cookery, published in 1796, New Englander Amelia Simmons gives these directions for tarts—pies without a top crust: "Stewed, strained and sweetened, put into paste No. 9, and baked gently." A competent cook of that day would know exactly how much to sweeten, how to make pastry number 9, and how long to bake. Queen Victoria, who did not bake her own tarts but did write her own journals, noted in her 1868 book that a dinner in the Scottish Highlands had ended "with a good tart of cranberries."

The wild cranberries of Massachusetts flower in June and July and are ready to pick by September. Picking any kind of berry by hand is backbreaking business and, eventually, wooden comb-like scoops were devised to pull berries off their vines, making the harvesting easier.

Initial attempts to cultivate cranberries were made in the early 1800s in Cape Cod. Revolutionary War veteran Henry Hall was probably not the first to notice that larger numbers of berries grew on bushes where the soil was covered with sand, but he was the first to do something about it. He figured out that acidic soil, sand, and fresh water were necessary for cranberry success and applied his theories. Per-acre yields increased.

By the 1840s, cranberries had been commercialized on Cape Cod and some other areas of Massachusetts and New Jersey. This coincided with the increasing affordability of granulated sugar, meaning more housewives could afford to sweeten their tart berries. Demand grew. Retired sea captains played a role in their cultivation, understanding as they did the berry's effectiveness against scurvy on long voyages. Some financed their bogs the same way they had financed their ships, by selling sixty-fourth interests in them to locals. Today, some of the Cape Cod bogs are still owned by a multitude of people who inherited them through the generations. And because cranberry bushes can live for generations, some on Cape Cod are said to date 150 years to the original plantings.

Cranberries were exported by the barrel to Virginia and other colonies to the south. Nearly every issue of Williamsburg's Virginia Gazette lists "all ships which have entered inwards in the Upper District of the James River" or arrived at ports near the city and describes the goods they imported. The months of November, December, and January are full of references to cranberries. "Imported December 5 on the Sparrow from Boston," reads a typical announcement, "5 barrels of Cranberries" along with "3 dozen chairs, casks of Madeira, axes, salt, chocolate, pickled codfish, cheese, fish, apples, and beer." The cranberry shipments typically originated in Boston or Salem. They were probably purchased wholesale by such merchants as Williamsburg's John Greenhow, William Prentis, and James Tarpley, who retailed smaller quantities to such customers as William Sparrow, cook to Governor Botetourt.

It was probably inevitable that cranberries would be associated with Christmas in the new republic. Their bright, shiny red color and their winter availability primed them for use on the table and the tree. Slow to spoil, they hold up for the entire twelve days of Christmas and longer.

The earliest American Christmas trees in the 1840s were decorated with homemade ornaments of fruits, nuts, candies, and other "sweetmeats," and it could not have taken long for the woman of the house to thread a large needle and string cranberries with popped corn to make a red and white holiday garland.

After the Civil War, "cranberry fever" broke out in New Jersey and other places. Much like the California Gold Rush of the 1850s or the dot.com frenzy of the 1990s, people hurried to invest in growing and harvesting cranberries in the belief that huge profits were assured. Not understanding the finicky plant's growing preferences or how the fruits were harvested, most enthusiasts of cranberry get-rich-quick schemes lost money.

After 400 years, cranberries are still an American phenomenon—the United States and Canada account for 96 percent of world production. After the Civil War, cultivation spread from New England to Wisconsin, where they flourished and knocked Massachusetts off its perch as the premier cranberry producer. Today Wisconsin grows more cranberries than any other state, and other northwestern states have joined in the production.

Wisconsin and Massachusetts have honored the berry by naming it their official state fruit. Two cranberry museums, one in Wisconsin and the other in Washington State, educate visitors about the history and harvesting of the fruit.

Commercial cranberries are harvested today by a wet or dry method. Dry harvesting involves rakes that remove the berries in a combing action. It is a more expensive process but does little damage to the berries and so is used to harvest the small percentage that will be sold fresh in supermarkets for Thanksgiving and Christmas. Wet harvesting is cheaper. The bogs are flooded with water and the plants are shaken with eggbeater-like tools. The action breaks off the berries and they float to the surface to be skimmed and taken to be crushed for juice that is made into jellies or beverages. Today, an acre of cranberry bog can produce up to 15,000 pounds of berries, ten times as much as a century ago and likely a hundred times more than during colonial times.

Cranberry Recipes

Frozen Cranberry Mousse

from Entertaining Ideas from Williamsburg

Cranberry and Orange Relish

from Favorite Meals from Williamsburg

For further reading:

- Read Mary Miley Thobald’s The Community Christmas Tree in America's Hometown, from the Christmas 2004 Journal.