Page content

A Christmas Essay

Christmas is a'coming,

The goose is getting fat,

Please put a penny in the old man's hat

by Ivor Noël Hume

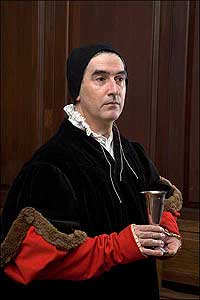

Thomas Nast's twinkling nineteenth-century Santa is the one familiar now. The older St. Nicholas was rather grim.

Sleigh bells ringing, children singing, Yule logs aglow, toy-filled stockings hanging by the hearth, Currier and Ives, Tiny Tim, and a beer baron's Clydesdales tromping through the snow. 'Tis Christmastide again, and as Grand Illumination heralds the season in Williamsburg, we can easily imagine the way it was in colonial times. Holly wreaths on every front door, mistletoe in the hallway, candle-lit tree in the parlor ringed round with brightly packaged gifts, and the sound of lantern-carrying carol singers amid the gently falling snowflakes. But snow? What snow? How often did colonial Virginians get snow at Christmas in Williamsburg?

If modern experience is the judge, the answer is: Not often. Though in 1775 it fell right on cue. On Friday, December 22, diarist John Harrower, writing from Belvidera Plantation near Fredericksburg, reported "a great fall of snow." But for him, Christmas Day passed unnoticed. In the previous year it snowed on the thirteenth, but Harrower's Christmas entry told only that he had no saddle on which to ride to church. Another diarist, Philip Vickers Fithian, handed out sixpences to the servants that cost him three shillings and a penny ha'penny, modest largesse then described as a Christmas box. But that was about the extent of Fithian's giving or receiving. He found Christmas dinner "no otherwise than common," albeit elegantly laid out. The Christmas Day entry of a much earlier diarist, William Byrd of Westover, recalled that in 1740 it was too cold for him to go to church, though he did have roast turkey on the table.

Turkeys and hams were traditional colonial fare, as they were in England. Even in the midst of a hot and sickly summer, a Yorktown resident thought to ship two "Christmas turkeys" to London, saying, "Mrs Mary Ambler will send hams to eat with them." But that was about as Christmassy as colonial Virginians became. It was no different in London for William Byrd in 1718, whose diary contributed only that he "ate some roast beef for dinner" in what we would consider a late lunch. No churchgoing, no gifts given or received. The following Christmas he was at sea on his way back to Virginia and eating plum pudding and boiled mutton, followed by roasted chestnuts and a bowl of punch with the captain. Byrd also conducted a service for the crew and wrote his own prayer.

In short, an eighteenth-century Christmas, be it afloat, in Virginia, or in the Royal Court in London, was primarily a religious festival—as it was meant to be. Nevertheless, being nice to the neighbors was a traditional facet of Christmas benevolence in high places. In 1772 the Virginia Gazette reported that at Windsor Lodge the Duke of Cumberland kept "open table for the Country People, for three Days, covered with Surloins of roast Beef, Plum Puddings, and minced Pies, the rich and ancient Food of Englishmen." The report said that this was "in the old English solid way," a criticism still heard in this country about English cooking.

In 1774 Christmas fell conveniently on a Sunday, and amid much regal pomp George III and Queen Charlotte received the sacrament in the Chapel-Royal from the hands of the Lord Bishop of London, assisted by the Lord Bishop of Chichester and the Clerk of the King's Closet. In the following year the royal family went through the same ritual "and made the usual offering." The reporting newspaper noted, however, that "the day has been kept with more strictness, by all ranks of people in this metropolis, than for some years past."

One immediately wonders what level of laxity had been perceived in previous years. It was, however, far more likely that antisocial behavior blossomed in the day after Christmas, that being the occasion for masters to reward servants and apprentices with ceramic money boxes containing their annual bonuses, which quickly went down their throats in the nearest taverns. 'Twas ever thus. As early as 1387 Geoffrey Chaucer wrote about the apprentice, his box, and his reputation for wild and riotous behavior. Although it is doubtful that any happy apprentice gave a thought to the origins of Boxing Day, the church was all too aware that the day of giving and receiving gifts could be traced to the pagan Roman Saturnalia, an event unfit for pious eyes or ears.

They saw it that way in Puritan Massachusetts. A law enacted in 1659 read: "Whosoever shall be found observing any such day as Christmas, or the like, either by forebearing of labor, feasting in any other way, shall be fined 5 shillings, and forbade the Festival of Christmas and kindred ones, superstitiously kept." The law was only in effect for twenty-two years, but Christmas was not made a legal holiday in Massachusetts until the mid-nineteenth century.

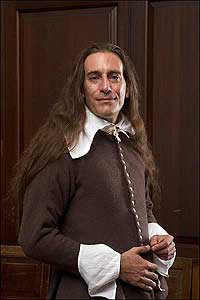

In England during the Cromwellian interregnum, attending a Christmas service could get one into deep trouble, as it did for diarist John Evelyn. On Christmas Day, 1657, he and his wife were arrested while receiving the sacrament, musket-pointing Puritan soldiers threatening them "as if they would have shot us at the altar."

Turkey was a traditional English main course for eighteenth-century Christmases, along with "Surloins of roast Beef" and hams, though colonists supped on the bird in summer, too.

Although there is evidence that the stroke of a Puritanical pen outlawed many an old English custom thought to have had pagan origins, in the tradition-shrouded recesses of the countryside such edicts were contemptuously ignored. Albeit in distorted forms, therefore, some traditions survived to be absorbed into the Christmas we still enjoy. Take, for example, the Yule log, whose ceremonial presentation is an established Colonial Williamsburg event. In the medieval centuries, when candles were expensive and hearths wide, the notion that the birth of the Christ child became the light of the world was reflected in the Christmas Eve burning of a large, knotted, and slow-burning log or wooden block. Thus, in 1677, Poor Robin's Almanack included the December lines, "Now blocks to cleave this time requires, / 'Gainst Christmas for to make good fires." Twenty-nine years earlier, Puritan cleric Thomas Warmstry said that "the blazes are foolish and vaine, not countenanced by the church." More to the point, oversized blazing logs were liable to catch cottage chimneys on fire.

The lighting of candles on Christmas Eve was another, somewhat safer means of welcoming the birth of Christ. In the sixteenth century, and probably earlier, single, very large candles called specifically "Christmas candles" were burned in churches and in homes, and it is this tradition of welcoming the infant Jesus with candles that has become part of the Colonial Williamsburg prelude to the sacred day.

Decorating one's home with ivy and other greenery was another tradition whose roots were dug deep in pagan Europe and were yet another feature of the Roman saturnalia that stretched from December 17 to 24. Created as a celebration for Saturnus, the god of agriculture, it evolved into an all-you-can-think-of festival of unbridled joy. The thirteenth-century historian Mathew Paris said it was characterized by "processions, singing, lighting candles, adorning the house with laurel and green trees, giving presents; the men dressed as women or masqueraded in the hides of animals."

The fir we cut to stand in the living-room corner may stem from the same classical source, though most of the myths surrounding it are Germanic—as College of William and Mary professor Charles Frederick Ernest Minnegerode well knew. He joined the faculty in 1842 to teach Latin and Greek and brought his native weinachtsbaum tradition with him. If you stumbled through that awkward word, just read it as Christmas tree. He set it up in the Courthouse Green home of his lawyer friend Beverley Tucker. It was not until Christmas Eve, 1915, however, that the City of Williamsburg chose Palace Green to erect its first public illuminated tree. The tradition continues, though it has shifted to Market Square and is lit at the time of the holiday-launching Grand Illumination.

Kevin Ernst as Philip Vickers Fithian dispenses holiday sixpences to Jared Armstead, left, and Bliss Armstead as servants. It was already a custom he felt obliged to follow.

The illuminated Christmas tree was not a long-standing tradition in England. Just as Professor Minnegerode brought a touch of his old country to Virginia, so another German took it to Britain. He was Albert Saxe-Coburg Gotha, who married Queen Victoria in 1840 and two years later was granted the rank of consort and enjoyed the distinction of introducing his weinachtsbaum to the English court. The year was 1842.

It is doubtful that many among the crowd following the Fife and Drum Corps down Duke of Gloucester Street give much thought to Professor Minnegerode's contribution to Williamsburg's Christmas or, indeed, to its German origins. Among the best known of the legends is that of a knight who on Christmas Eve was riding through a forest when he saw a strange light glimmering between the trees. Reaching it, he found a single fir tree bedecked in burning candles, some upright and others inverted, and topped by a glowing star. Returning home, his mother told him that he had been privileged to see the Tree of Humanity. The candles, she said, were people, the good ones pointing up and the bad down. The glowing star was the Infant Jesus watching over all humanity.

Today, of course, few of us risk using anything but electric candles, but I recall a Christmas at Carter's Grove when a ceiling-height tree in the hall was so bedecked with flaming candles that the heat threatened to set the house on fire.

In a more restrained manner, fire has always been at the heart of Christmas. In pre-Christian Germany in houses where smoke escaped through a hole in the roof rather than up a chimney, the winter solstice was dedicated to Hertha, the goddess of domesticity. The room was decked with evergreens and a great fire was laid on a large, flat altar stone set in the center. In the midst of feasting, the goddess would descend through the smoke to bestow good luck on the host and his guests. Thus, according to some mythologists, the Hertha stone became our hearthstones, and the legend explains why, rather than entering in a reasonable and civilized way, Santa Claus comes down the chimney.

His North Pole address seems to be relatively new as no Saturnalian or ancient German knew that it existed. But Santa's alter ego, a grim-visaged Saint Nicholas, came out of the German forests riding a white horse carrying a basket of gifts for good children and a fistful of birch rods with which to beat the bad. The saint's demon attendant, Pelznickle, who did the punishing and who today has been transformed into a cute polar elf, provided an additional touch of menace. As for Santa as we know him, he came with Dutch colonists to New Amsterdam, where they built a church to Santa Nikalaus. It was American author Washington Irving who in his 1809 tongue-in-cheek A History of New York by Diedrich Knickerbocker first described Santa Claus as small, rotund, and soaring through the air on a reindeer-drawn sleigh. Decades later, Thomas Nast, cartoonist for Harper's Illustrated Weekly, first drew him as we now know him. Nast also gave us the Democrats' donkey, and the GOP elephant.

English writer John Evelyn and his wife, portrayed by Penn Russell and Lori Loughrey, found themselves in trouble with Cromwellian authorities, in the person of Willie Balderson, for receiving Christmas sacrament from their priest, here Robert Doares.

And what about carols? Christmas without carolers would be like—well, like holly without ivy. The word is said to derive from the Latin cantare, to sing, and rola, an expression of joy, and its earliest surviving text dates from the thirteenth century. But caroling being a monastic activity, it fell into disfavor in the reign of Henry VIII, later to be revived in more secular forms only to be condemned by the Puritans. By the time the British got over that hurdle, old-style carols were considered antiquated. Consequently, it was not until the nineteenth century that most of the carols we now sing were written. "Silent Night" was first published in 1840, "Hark the Herald Angels Sing" in 1856, "O Come, All Ye Faithful" was not translated into English until 1841, and "O Little Town of Bethlehem" was written for a Philadelphia Sunday School in 1868.

In truth, most of the panoply of Christmas is the product of pagan tradition, of Victorian sentimentality, and of modern marketing that keeps millions of the world's elves in the manufacturing business. Even the mandatory Christmas cards to and from people you scarcely remember and probably wouldn't like if you saw them now have roots as shallow as the sentiments expressed. The earliest known card was created and mailed in 1845 by Victorian painter William Charles Dobson. A year later, another painter, John Calcott Horsley, was asked to provide a lithographed card to be sent out by the too-busy Sir Henry Cole, keeper of the records at the British Treasury Office, and thanks to him we have ever since been wishing one and all a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!

For my part I leave you with some much older Christmas wishes in verses that predate Thomas Nast and even Charles Dickens, and which eloquently portray a yearning for imagined simpler days and happier hearts:

Too busy or too indolent to write personal greetings, Sir Henry Cole stands accused of being the sender of the second mass-produced Christmas and New Year's card in 1846. He at least wrote in the recipient's name and signed his own on the line.

Come, help me to raise

Loud songs to the praise

Of good old English pleasures:

To the Christmas cheer,

And the foaming beer,

And the buttery's solid treasures;— To the stout sirloin,

And the rich spiced wine,

And the boar's head grimly staring;

To the frumenty,

And the hot mince pie,

Which all folks were for sharing;—To the holly and bay,

In their green array,

Spread over the walls and dishes;

To the swinging sup

Of the wassail cup,

With its toasted healths and wishes;—To the honest bliss

Of the hearty kiss,

Where the mistletoe was swinging;

When the berry white,

Was claimed by right,

On the pale green branch clinging;—When the warm blush came

From a guiltless shame,

And the lips, so bold in stealing,

Had never broke

The vows they spoke,

Of truth and manly feeling;—To the story told

By the gossip old,

O'er the embers dimly glowing,

While the pattering sleet

On the casements beat,

And the blast was hoarsely blowing;—

To the tuneful waitAt the mansion gate,

Or the glad, sweet voices blending,

When the carol rose,

At the midnight's close,

To the sleeper's ear ascending;—

To all pleasant ways,In those ancient days,

When the good folks knew their station;

When God was fear'd,

And the king revered,

By the hearts of a grateful nation;—When a father's will

Was sacred still,

As a law, by his children heeded;

And none could brook

The mild sweet look,

When a mother gently pleaded;—When the jest profane

Of the light and vain

With a smile was never greeted;

And each smooth pretense,

By plain good sense,

With its true desert was treated.

First published at Christmastide in 1832, the wistful verses clearly reflected dismay at lost contentment, the eroding of family values, and the decline of morality and civility. Now, 173 Christmases later, what else is new?

Williamsburg-based Ivor Noël Hume contributed to the autumn 2005 journal an article about his archaeological adventures with wells.