Page content

Online Extras

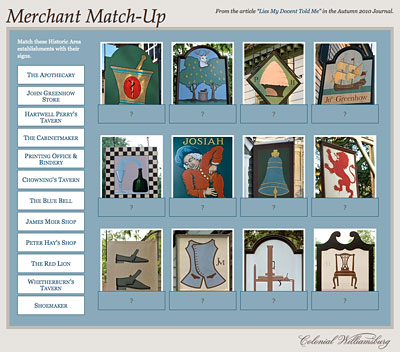

Merchant Match-Up Game

Lies My Docent

Told Me

by Mary Miley Theobald

In the game Telephone, one person whispers a story to the person beside him, who repeats it to the next, and so forth around a circle until it comes out of the last person’s mouth mangled and embellished. According to Susan Smyer, director of the WaterWorks Museum of Houston, Texas, that sort of repetition is one way inaccurate information is passed along in museums and historic houses.

Smyer, who has led panel discussions at conferences on museum myths, says legends are also perpetuated by docents who “succumb to the lure of a really great story or a good laugh, even when they know it isn’t the truth,” who mistakenly transfer present-day thinking to the past, or who apply stories that are true in one time or area to another where they are not. Such myths, she says, “are harder to kill than vampires.”

Among the fictions that will not die:

Craig McDougal

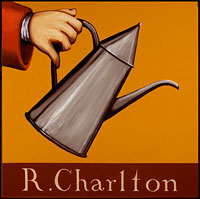

Eighteenth-century business signs, which Charlton’s Coffeehouse’s mimics above, were not concessions to illiteracy.

Lie 1: Most people were illiterate, so colonial shop signs had to have pictures.

Shop signs and inn signs with pictures were no doubt helpful to people who couldn’t read, but mass illiteracy does not account for their use.

Most white colonists were literate; most blacks were not. Percentages changed over time, and the only way to estimate is by using signatures as evidence of literacy, though it is likely that some people could write their names but not read or write much else.

A study of legal documents from the second half of the seventeenth century found that 60 percent of the white men and 25 percent of the white women could read. Another shows that in the Williamsburg area in the middle of the eighteenth century, 94 percent of white males and 56 percent of white females could read. Evidence strongly suggests that nearly all Virginia property owners and heads of households during the late colonial period were literate. In New England, literacy rates were higher because there were more schools and nearly everyone learned to read to study the Bible.

Wealth and gender were the strongest predictors of literacy. Around the time of the American Revolution, two-thirds to 90 percent of white males could read, and half to two-thirds of white women.

Ann Wager’s Bray School for African American children lets the air out of the claim that all blacks were kept illiterate.

Lie 2: It was illegal to teach African Americans, slave or free, to read

and write.

In nineteenth-century Virginia, this was true, but not in the colonial period. In 1831, the Nat Turner uprising so frightened slaveholders that the legislature enacted a slew of laws to restrict slave activities. One prohibited teaching African Americans to read so that they could not easily communicate to plan rebellion. But before this date and after it, there were many examples of literate African Americans, though never a great percentage.

In Williamsburg, Ann Wager operated a school for black children from 1760 until 1774. A widow, she was hired to instruct slave children by the Bray Associates, a philanthropic group that paid the expenses. The Bray School, as it was called, existed to “instruct Negro Children in the Principles of the Christian Religion.”

Enrollment was not limited to boys, as down the street at the all-white, all-male College of William and Mary. The Bray Associates anticipated that girls would be taught, too. They directed the hiring of a female teacher:

As tis probable that Some of Each Sex may be sent for Instruction, The Associates are therefore of the opinion that a Mistress will be preferable to a Master, as she may teach the Girls to Sew knit, &c. as well as all to read & say their Catechism. They think 30 Children or thereabout will Sufficiently employ one person.

Most Bray School students were enslaved, however, a few free black children also attended the classes, conducted in Wager’s home.

The Bray School was among several educating African American children. Nevertheless, most slaves got no schooling at all.

Lies 3, 4 & 5: Women secluded themselves when pregnant, were pilloried for showing their ankles, and had tiny waists.

The persistent secluded pregnancies falsehood is trotted out as well for women of the nineteenth century, or Victorian era, but there is little evidence to support the claim for either century. Poor and middle-class women could not remain sequestered indoors for months on end— they had too much work to do—and wealthy women, who theoretically could have, did not want to. Linda Baumgarten, Colonial Williamsburg’s curator of textiles, writes in What Clothes Reveal that not only did colonial era women venture outside their homes during pregnancy, but they enjoyed active social lives, dining with friends, attending religious services and cultural events, and going about their daily business. Letters and diaries of the period provide the evidence.

Though there have been periods when women didn’t bare their ankles, the colonial era was not one of them. “Skirt length,” says Baumgarten, “was a matter of both fashion and occasion. Formal clothing usually has longer skirts. Work clothing was nearly always shorter for practical reasons.” For example, polonaise-style gowns in the 1770s and early 1780s are shorter and reveal the ankle. And during the workday, a woman might hike up her hem and tuck it into her waist to get it out of the way. No one went to the pillory.

Women’s sizes then and now are not so different, and costumes in the Smithsonian and Colonial Williamsburg collections prove it. Baumgarten’s measurements of eighteenth-century stays and gowns show waist sizes from about twenty-one to thirty-six inches. An optical illusion fuels this myth: long gowns with wide panniers and full skirts make the waist seem smaller, as does the triangular stomacher that narrows to a point just below the waist.

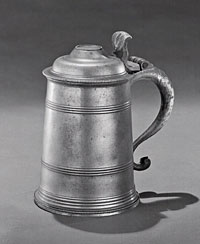

Hans Lorenz

Pewter, such as that in the tankard above, was a source of possible lead poisoning, though far from the only one.

Lies 6, 7 & 8: Lead in pewter housewares poisoned many. During the Revolution, people melted plates and such to cast bullets for their heavy and awkward guns.

Pewter is an alloy of mostly tin mixed with copper, antimony, brass, zinc, bismuth, or lead. A 1970s Winterthur Museum study showed fine eighteenth-century pewter contained no lead, but that lower quality pewter often did. Nearly everyone was exposed to pewter plates, utensils, and drinking vessels used in kitchens or on the tables of those who couldn’t afford sterling—which was most of the population. Most colonials also came into daily contact with lead through lead-glazed pottery, lead crystal, musket balls, lead paint, lead solder, and other sources. The richer the person, the more lead they consumed with their food, because servants, slaves, and the poor ate with wooden utensils.

Colonial Williamsburg apothecaries Robin Kipps and Sharon Cotner say the noxious effects of lead were well known, if not well understood. Lead poisoning had been recognized since ancient Rome, when it became obvious that men working with lead, like miners and plumbers, suffered from its symptoms.

Smithsonian scientists have analyzed lead content in colonists’ bones. Modern Americans generally have less than 20 parts per million in their bones, and it takes about 50 ppm before symptoms become noticeable. One wealthy mid-seventeenth century Virginian had a whopping 149 ppm. “But there is no way,” Kipps said, “to determine how much of the lead in a body was due to pewter versus all the other sources.”

It seems safe to say that pewter contributed to lead poisoning, but was not the most significant source of lead. Kipps and Cotner said medical texts of the period do not connect lead poisoning and the use of pewter, crystal, and ceramics, so presumably no one else did either.

Beginning in the middle of the eighteenth century, pewter was replaced by ceramic plates and glass drinking vessels made available through mass production. Modern pewter, used mostly in decorative pieces, is lead free and usually so marked.

Speaking of deadly pewter, have you heard that during the Revolution people melted mugs and plates to make bullets? Bullet molds were intended for making lead bullets. “In a pinch,” says Colonial Williamsburg apprentice gunsmith Richard Sullivan, “you could use pewter even though it would be inferior to lead. But I know of no accounts of such a practice.”

With bullets, heavier is better. Pewter would work, but a bullet made mostly of tin wouldn’t go as far, would lose velocity more quickly, and would have less energy when it struck. Melting down one’s pewter plates and utensils might have provided ammunition that was better than nothing, but the practice was hardly widespread.

Heavy guns? A standard British military gun of the eighteenth century weighed about the same as the United States Army’s nine-and-a-half-pound World War II rifle, the M1 Garand. Gunsmith Sullivan said most colonial guns weighed from six to ten pounds.

An unequal riser on a staircase was the result of faulty carpentry, not a colonial burglar detector to trip thieves.

Lie 9: Stairs were sometimes built with a short riser to trip burglars.

It makes a great visual: In the dead of night, comes a burglar. Sneaking up stairs, his foot reaches a riser unexpectedly shorter than the rest, and his foot comes down. Thud! The noise wakes the household, and the thief is caught.

The myth of the burglar alarm staircase has been related in historic houses throughout the country, including the Williamsburg home of Peyton Randolph. The back staircase in the 1718 portion of the house has seventeen steps, and the top riser is shorter than the rest.

Why? Garland Wood, Colonial Williamsburg’s master carpenter, said, “Building stairs is hard. It’s not natural or intuitive. Nineteenth and twentieth century stair-building books—yes, people wrote entire books about how to build a staircase—show mathematically precise ways to use modern framing squares to lay out the stringers and make the cutouts for the treads and risers. Stairs were laid out so precisely that some were built in workshops off-site and then brought in and installed.

“But that’s not the way stairs were built in Williamsburg in the colonial era. Most stairs in the Historic Area were built from the bottom up, one riser and tread at a time. Invariably, error creeps in as more treads are installed, which leads to the final riser being a little tall or short.”

It took an unusually skilled carpenter to build a perfect staircase on-site. The average carpenter could build one that got you upstairs, but not with perfectly aligned treads and risers. Uneven risers could also have been caused by inferior workmanship during repairs, or by the house settling. It was never intentional.

Wigs were sometimes baked in ovens in dough, but to say they were baked in bread is more entertaining than true.

Lie 10: Wigs were baked in loaves of bread to set the hair.

Like many myths, this one has a kernel of truth. To turn hair into a wig, you took fresh hanks of hair, rolled them onto porcelain curlers, and tied them with string. A wigmaker boiled eight or nine of these packets, as they were called, and oven-dried them. For customers who wanted a frizzy-style wig, the wigmaker wrapped the dried packets in cheesecloth and took them to a bakery, where they were encased in a sort of dough and baked again. “Not all hair was baked a second time,” said Betty Myers, supervisor of Colonial Williamsburg’s Wig Shop, “just the hair that was being prepared for the frizz look.”

In the 1767 French work Art of the Wigmaker, François Alexandre de Garsault describes baking hair wound on curlers, but never a whole wig. After boiling and drying the hair curlers,

and arranging them in several layers one on top of the other, the whole is given the form of a loaf. Tie the package with string, and take it to the Ginger-bread Maker or the Baker, who having received it surrounds it with a paste of rye flour, puts it in a moderate oven and cooks it.

Calling the bunch of curlers a “loaf ” and mentioning a rye flour paste, Garsault seems to have inadvertently started the idea of cooking wigs inside loaves of bread.

And speaking of wigs, that phrase “flip your wig” doesn’t seem to have been an eighteenth-century expression at all, but a twentieth-century bit of American slang meaning “to go crazy.” According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first recorded use of the term was in 1952.

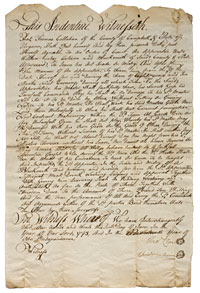

Apprenticeships, witnessed in contracts such as the one above, were of variable lengths, not an iron seven years.

Lie 11: Apprenticeships lasted

seven years.

Some Virginia apprenticeship contracts specify four years. Others say the apprenticeship would last until the boy reached twenty-one, no matter his age at the start. Some evidence suggests family apprenticeships—a man training a son or a younger brother—tended to be shorter than average.

After the apprenticeship was over, the young person could work for wages as a journeyman or, if he had the means, set up on his own. A master was one who had his own shop. A master was not necessarily more skilled than a journeyman; the term indicated that he worked for himself rather than for wages.

Some trades, like barbers or bookbinders, required relatively little investment in tools and overhead to set up one’s own shop; others, like cabinetmakers or goldsmiths, required a good deal of start-up capital, making it difficult for a journeyman to become a master.

Lie 12: Mirrors came in multiple pieces

to

avoid the tax on large panes.

The dread mirror tax, like the second-story tax, the closet, and other mythological duties, never existed.

Large mirrors were segmented because it was difficult to manufacture large, flat pieces of glass, not to mention harder to transport them without breaking, and therefore they were more expensive.

The legend may trace to 1767’s Townshend Revenue Acts, which mandated taxes on certain items imported to America from England, including glass. “For every hundred weight avoirdupois of crown, plate, flint, and white glass, four shillings and eight pence,” it reads. Plate glass, used for mirrors and large windows, was thin and polished and contained few impurities.

After vigorous protest, Parliament repealed the Townshend duties in 1770—except the tax on tea—so any impost on glass was short-lived and never collected. There was no mirror tax in the thirteen colonies.

Author Mary Theobald, thanks journal readers who wrote to share myths they had heard at historic properties throughout the country. She hopes this article and the one preceding it in the winter 2008 journal are sufficient penance for her own crime when, working as a tour guide during the summer of 1973, she told visitors to the Peyton Randolph House all about the, ahem, burglar alarm staircase.