Page content

Captain Smith Departs

The Question Still Remains: Hero or Betrayer?

by Andrew G. Gardner

Photography by Dave Doody

Online Extras

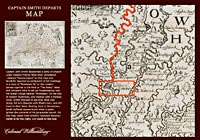

Trace Captain Smith's route up the James River

-

Extra Images

His enemies stirred a plot to murder Captain John Smith in his bed, but it fizzled when the assassin’s nerve failed him at the point of pulling the trigger. Interpreter Mark Schneider is the sleeping Smith, Willie Balderson the unstrung gunman.

From left, John Templin, Gregory Schneck, and Dennis Parris as Percy, Ratcliffe, and Archer taking allegations of Smith’s misdeeds from Scott Krogh as a young Jamestowner. They sent Smith back to England to answer charges.

His presidency blasted by faction and his body by gunpowder, Captain John Smith exited Virginia, never to return, October 4, 1609. As he departed, rival captain John Ratcliffe wrote, “The man is sent home to answer some misdemeanors whereof I perswade me he can scarcly clear him selfe from great imputation of blame.”

History hints at what those misdemeanors were, but it does not document them. We know something of what went on at the end of Smith’s service to the Virginia Company of London—the colony’s owner— but not enough to get at the whole truth of his downfall. Enough to ask questions, but not enough to answer them all.

With Smith sailed eight or nine witnesses who were to appear against him in a company court. “Many got their passes by promising in England to say much against him,” Smith said, but they could swear to nothing except what “all men did knowe was most false and untrue.” We do not know if, or what, they testified. No record of a trial survives.

Some of what we do know comes from other enemies—successor George Percy’s A Trewe Relacyon, and A Letter of M. Gabriel Archar—and a little more from young colonist Henry Spelman’s Relation of Virginia. Much more comes from accounts Smith penned, or gathered from admirers, edited, and carried to the press in such works as The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles.

“There are no other accounts as extensive as Smith’s. This period is rich in eyewitness narratives, but no one else wrote as much as Smith or provided a coherent story of the whole period,” says James Horn, who has written books about Smith and Jamestown, says, “Of course Smith’s writing is biased, but he was well aware that the different editions of his experiences, written years later, would guarantee that his side of the story would be what everyone remembers. In effect the history was written by Smith … Smith the survivor.”

Unless otherwise attributed, the account that follows is based on what Smith reproduced from what was “Written by Richard Pots, Clarke of the Council, William Tankard, and G.P.,” fellow colonists and admirers. It is said that the best witness for the prosecution is the defendant. To prosecute any examination of Captain Smith’s departure, we mostly have to take him at his word.

Smith became president of the Jamestown enterprise September 10, 1608, taking the first chair on a council with on-site charge of Virginia affairs. His term was to last a year. He had, two months before, forced Captain John Ratcliffe from the post. Ratcliffe, who seems to have been using an alias, was part of an anti-Smith clique formed with such gentlemen as Captain John Martin and Recorder Gabriel Archer.

Smith persuaded newcomer Matthew Scrivener to warm the chief executive’s seat while he explored the Chesapeake, until he returned and took over. Three weeks into his administration, a supply fleet arrived, the colony’s second. When the ships set back for England in December, they carried off Ratcliffe and Archer under arrest for mutiny, and Martin. Smith dispatched a letter to London that said in part: “Cap’n Ratcliffe is . . . a poore counterfeited Imposture. I have sent you him home least the Company should cut his throat. . . . if he and Archer should returne againe, they are sufficeinet to keep us always in factions.”

In England, Smith’s detractors told tales of sickness, food shortages, desertions, Indian fights, and squabbling among Jamestown’s leaders. Already frustrated by the surplus of Jamestown disasters, and the deficits on Jamestown investments, the Virginia Company decided on bold solutions for the colony’s problems.

The end of the story begins August 11, 1609, when up James River limped the Lion, the Falcon, the Unity, and the Blessing, the first of eight ships from a third supply carrying 500 colonists—five times as many as ever were sent at one time. The company’s hope was the addition would jump-start its business. But Virginia, home to about 200 languishing English, had no warning of the newcomers, no accommodation for them, and little for them to eat.

About 350 of the 500 arrived that autumn, sea-beaten and bedraggled, among them Ratcliffe, Archer, and Martin. A hurricane hit the fleet in the West Indies. Its flagship, Sea Venture, with 150 aboard, including commanders Christopher Newport, Sir Thomas Gates, and Sir George Somers, foundered in Bermuda, unbeknownst to anyone else, marooned there till spring. The shipwreck’s story may have informed William Shakespeare’s The Tempest.

With the castaways was a new Virginia charter, a commission the company prepared “to redresse those jarres and ill proceedings” in Jamestown. It reformed the government and sacked Smith—answering the prayers of his enemies.

During the voyage those enemies persuaded the newcomers of Smith’s unfitness to govern. Landing, they disputed the month left in his presidency, but Smith, declining to surrender power absent the sidetracked charter in Bermuda, “laid some by their heels”—which means he fettered or confined them.

Francis West, a brother to the English Lord Delaware and the captain’s designated replacement, became a sort of president-in-waiting. For now, Smith ordered him, a ship full of supplies, and 120 men to go upriver to the falls at modern Richmond, and Martin to take about that many more downriver to modern Suffolk. Splitting up the arrivals relieved pressure on the forage in Jamestown’s neighborhood.

Smith said he turned the presidency over to Martin. But in three hours Martin gave it back—“he knowing his owne insufficiency, and the companies untowardnesse and little regard of him”—and left. Smith soon left, too, setting off upriver with five soldiers to check on West’s settlement. En route, they ran into West heading back to Jamestown. Puzzled that West could so soon leave the work at the falls, Smith nevertheless went on. He found the English planted “inconsiderately, in a place note onely subject to the rivers inundation, but round invironed with many intolerable inconveniences.” They called that place West’s Fort.

Nearby was a better-sited Powhatan Indian village. Smith negotiated for it to reseat West’s men, christened it Nonsuch, and got the Indians’ promise to contribute food to its new inmates in return for an alliance. Smith thought West’s people should have been thankful, “But both this excellent place and those good Conditions did those furies refuse, contemning both him his kinde care, and authoritie.”

Worse, the Indians complained that West’s men were “stealing their corne, robbing their gardens, beating them, breaking their houses and keeping some prisoners.” Though out of love for Smith the Powhatans had not resisted, they told him they “desired pardon if hereafter they defended themselves. . . . So much they importuned him to punish their misdemeanors, as they offered (if he would leade them) to fight for him against them.”

Smith and his soldiers confronted the West’s Fort crew and imprisoned its leaders, “till by their multitudes being an hundred and twentie they forced him to retire.” Retreating, he commandeered one of their boats, took their supply ship, and sailed away with six months of their provisions. He does not say that he paused to warn his countrymen of the Indians’ intentions.

Percy said Smith “pceaveinge bothe his authority and Person neglected incensed and Animated the salvages against Capte West and his company . . . Reporteing unto them that our men had noe more powder left them then wolde serve for one volley of shott.”

Spelman was, unlike Percy, at the falls. He said that, “unkindeness arising between” Smith and West’s men, “Captaine Smith at that time repliede litell but afterward conspired with the Powhatan to kill Capt Weste.”

No sooner than Smith sailed, a dozen Powhatans attacked West’s men, and “finding some stragling abroad in the woods: they slew many, and so affrighted the rest, as their prisoners escaped, and they safely retyred, with the swords and cloakes of those they had slaine.”

A half-league downstream, Smith’s stolen vessel ran aground, and perhaps waiting for high tide to float her off, he improved the time by summoning West’s crew to parley. They submitted to Smith’s authority. He set six or seven of them by the heels, sent the rest back to Nonsuch, put the colonists to work on the place, and “appeased” the Indians “redelivering to either party their former losses.”

“New turboyles did arise,” however, when West returned from Jamestown. It is easy to imagine West, a confident young gentleman of worth and an aristocratic pedigree, would tell Smith, a man of yeoman birth, to take a hike.

“Class difference was important in seventeenth-century English society,” Horn says. “There’s no reason to think that it didn’t travel to the New World . . . and surrounding that issue, would potentially be problems with leadership.”

West’s English turned again against Smith, and decamped Nonsuch for West’s Fort. Smith “left them to their fortunes,” and reembarked for the seventy-mile river trip to Jamestown.

“Sleeping in his boate, accidentalie, one fired his powder bag, which tore the flesh from his body and thighs, nine or ten inches square in a most pittiful manner.” Smith leapt into the river to douse the burn. It may be that a spark from the match on someone’s musket was the cause of the fire. But there has also sprung up the theory that it was a misfired murder plot.

“The explanation of an accident doesn’t ring true,” Horn says. “I have never found a single reference to any other similar incident . . . a spark igniting a powder bag. In my opinion, someone was trying to bump him off.”

Ratcliffe and Archer and “the rest of their Confederates” had been again accused of mutiny, and when the suffering Smith reached Jamestown, they were coming to trial:

Fearing a just reward for their deserts, seing the President, unable to stand, and neere bereft of his senses by reason of his torment, they had plotted to have him murdered in his bed. But his heart did faile him that should have given fire to that mercilesse Pistoll. So not finding that course to be the best, they joined together to usurpe the government, thereby to escape their punishment.

Does this attempt on Smith’s life add credence to the idea of someone trying to kill him on the boat?

All Percy says is, “Capt Rattliefe, Archer and Martin practysed against him and deposed him of his govermentt.” Smith said he afterward got up to go to persuade someone else to take the government but could “finde none hee thought fit for it would accept it.” Seeing him gone, “they perswaded Master Percy to . . . be their President. Within lesse then an houre was this mutation begun and concluded.” He let his expired commission be stolen “to bee free from the danger of their malice.”

The third supply’s return for England waited three weeks while charges against Smith were drawn and statements taken.

So diligent they were in this businesse, that what any could remember, hee had ever done or saide in mirthe, or passion, or by some circumstantiall oath, it was applied to their fittest use . . . now all those men Smith had either whipped, punished or any way disgraced, had free powere and liberty to say and sweare any thing.

Whatever the truth of the allegations, this time his rivals had him. Captain Smith shipped out of Virginia a prisoner. Winter brought the Starving Time, a period of famine that devolved into cannibalism, and that Smith’s admirers said would not have happened had he remained.

Ignore Percy’s, Archer’s, and Spelman’s charges for the moment—among their allegations that Smith conspired with West’s Fort’s Indian enemies, interfered with West’s command, and compassed West’s murder—and consider only the testimony Smith published in his behalf.

It says, at least, that he with doubtful authority twice laid by the heels West’s Fort colonists, that after threatening them and being repulsed, stole from his countryman a boat and the ship containing their provisions, did not warn them of the threat of an impending Indian attack, and afterward took advantage of his relationship with the Powhatan to threaten the English at the falls into submission to his orders.

If treasons, like treacheries, are defined as acts of deliberate betrayal, and they are, it is hard to see how to convict Smith of unblemished loyalty. But, at this remove, to say much more would be injudicious. It is impossible, four hundred years later, to recover the context, never mind the motives, of the actions of a man like Smith in circumstances so complex, and turbid. Never mind his opponents’ and the Indians’. But if we are interested in history, we are obliged to think on them.

Smith lived to be fifty-two, publishing his life’s adventures, scorning his old rivals. He explored the New England coast in 1614. In 1621 he petitioned the Virginia Company for recompense of his Jamestown exploits, but we do not know that outcome, either. To be honest, we do not know whether he deserved it. Was he hero or charlatan? Perhaps a bit of both, or neither?

Horn says that because there are gaps in what we have of Smith, it is difficult to judge him, but “that the Virginia colony survived at all, owes a great deal to Smith.

“The whole of the thrust to accelerate the colonization that we saw with the new charter and the Tempest Fleet probably came as a result of what Smith achieved with his earliest explorations and mapmaking. He was a capable man who made a huge contribution. Without Smith’s determination, you have to wonder if they would have made it through the first two years . . . and that in turn begs the question, if he had not been injured and had remained in Virginia, could he have prevented the starving times that followed?”

Extra Images

Andrew Gardner, who writes on Canada's Salt Spring Island, contributed to the summer 2008 journal an article about Christopher Columbus.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Philip L. Barbour, ed., The Complete Works of Captain John Smith (1580−1631), 3 vols. (Chapel Hill, NC, 1986).

- James Horn, A Land as God Made It: Jamestown and the Birth of America (New York, 2005).

- “A Letter of M. Gabriel Archar, Touching the Voyage of the Fleet of Ships, Which Arrived at Virginia, Without Sir Tho. Gates, and Sir George Summers, 1609. 31 August 1609,” in The Jamestown Voyages under the First Charter, 1606−1609, ed. Philip Barbour (London, 1969).

- George Percy, “A Trewe Relacyon of the Pcedeinges and Ocurrentes of Momente wch have hapned in Virginia from the Tyme Sr Thomas Gates was shippwracke uppon the Bermudas ano 1609 untill my depture outt of the Country wch was ano Dni 1612. By George Percy (post1612),” in Virginia: Four Personal Narratives (New York: Arno Press, 1972.

- Captain John Smith: Writings with Other Narratives of Roanoke, Jamestown, and the First English Settlement of America, ed. James Horn (New York, 2007).

- Henry Spelman, “Relation of Virginea” (1613), in The Travels and Works of Captain John Smith, ed. Edward Arber (Edinburgh, 1910).