Page content

The Bugs that Bugged the Colonists

The weevil wrought evil, but the bee brought sweetness and light

text by David Robinson

photos by Dave Doody

A 1787 illustration of a bee by George Adams. The bee may sting, but by pollinating crops, it is more boon than pest to humans.

Bugs worked their way into the grains and seeds and foodstuffs people gathered, consuming and befouling them. Among the most mischievous, weevils bored into hardtack aboard ship, eating away at it but also making it easier for sailors, here Justin Clement, to eat.

"Musketas and Flies" were two of the Virginia pestilents John Smith described in his Historie. The itching bites of the mosquito, left, harassed the new colonists. The recent collapse of bee colonies around the world reminds us how essential they are to our crops.

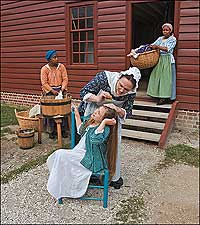

Children with head lice, the bane of parents, to the present. In front of the Peyton Randolph kitchen, Carolyn Wilson scrapes a lice comb through Rebekah Horsting's hair while Bridgette Houston, left, and Imani Turner wash the body lice out of clothes.

Small warriors against mankind, in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century illustrations: Below, a flea, a louse, a cockroach, and a fly. The planet was theirs before the dinosaurs and will remain in the clutches of their several legs after humans are gone.

To cure the ague, or chills, fever, and sweating, you might try stuffing spider's web into a baked apple, and eating it. But it could do you more harm than good. One colonial lady took the treatment, but nothing happened. So, she tried a second dose. Peter Kalm, a Swedish naturalist who visited America in the 1740s, tells us what happened when she ate a third. The poor soul "fell into such a coma that she looked dead." Ah, but in a few hours she was up and feeling fine, "It was," Kalm wrote, "both a severe and adventurous cure." For good or ills, insects were part of life for the colonists. Some were welcome; they pollinated crops and flowerbeds, gave honey and candle wax, and spun a little silk. But then there were bugs that really bugged them. These ate their crops, infested their larders, shared their beds, sucked their blood, animated their clothes, and set up lousekeeping in their scalps. Pain followed the stab of a stinger. Disease lurked in the buzz of tiny wings, in the pinch of a bite, on feet that could cling to a ceiling or a wavy pane of bull's-eye glass. Death itself might hang in a web—or almost, if it were baked in an apple.

Colonists complained about wolves and rattlesnakes, the "sauvages," and the "hideous wilderness" that confronted them. But they jotted down little about the little creatures, the insects that were their daily and nightly companions. The wolves and snakes could be killed, the Indians befriended, the wilderness logged and plowed and planted. The insects could only be endured. And they had better be, said William Bradford, governor of the Plimoth colony. Treasurer James Sherley had written him from London that the Massachusetts Bay Company was hearing ominous reports—thievery, sloth, bad water, marauding wolves, pesky mosquitoes. "These are the cheefe objections," he said; "I pray you consider them and answer them by the first conveniencie." Bradford did: "They are too delicate and unfitted to begine new plantations and colonies that cannot enduer the biting of a muskeeto," he said, advising "such to keepe at home till at least they be muskeeto-proofe." In Mourt's Relation, the chronicle which he probably co-authored, the Indians seemed to endure well the "lice & fleas indoors, and muskeetoes without," which sent visiting colonists scurrying back to Plimoth to get some relief.

Things were no better in Jamestown. In his 1624 Generall Historie of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles, Captain John Smith complained not only of "Musketas and Flies" but of a new annoyance, "a certaine India Bug, called by the Spaniards a Cacarootch, the which creeping into Chests they eat and defile with their ill-scented dung." The Spanish word he mangled was cucaracha, which translates as "contemptible little caterpillar." The name evolved into "cock-roche" in the 1700s, "cock-roach" in the 1800s, and "roach" today, but the family of bugs it describes has been around since the dinosaurs.

Perhaps Thomas Mouffet, an English doctor in physick, had not read Smith's Historie when he wrote in 1658 of these "fliers of the night." He called them "moths"—and a few other things: "nasty, cruel, rough, theeving, living of nocturnal depredations after an infamous manner." Even so, said he, "God hath endued them with sundry vertues," whatever those might have been. He saw fewer "vertues" in "the unsavory or stinking Moth," however. It "doth not only annoy those that stand near it, but offends all the place thereabouts with its filthy favor."

Mouffet erred in calling the cockroach a moth, even as did the Spaniards in calling it a caterpillar. But his interest in insects won him a role in a nursery rhyme as the arachnophobic Little Miss Muffet. The spider that sat down beside her was venomous; all spiders are. But few can kill a human. And in days before indoor plumbing, the human was usually a male. The black widow does not see very well; she spins a web and rushes out to bite the first thing that touches it. And what better place for a web than the hole in an outhouse seat, with its steady traffic of flies? For anatomical reasons—there is no delicate way to say this—a seated man was far more likely to touch the web than was his wife—or, all too soon, his widow.

There was more to endure than "Musketas and Flies" and the "Cacarootch." Just getting to the New World in the plodding, cramped wooden ships of the day required a long and perilous sea voyage with a host of unsavory shipmates, some with two legs, of course, but many more with six, eight, none, or too many to count. In the close confines of a sailing ship, lice on one passenger at the start of a crossing could mean lice on all by journey's end. These pests came—and still do—in three models, each with its own preferred territory: head lice, body lice, and crab lice, named for their resemblance to a crab, which prefer the nether regions.

A sailing ship was still a lousy way to get to America when Gottlieb Mittelberger made a trip from Germany to Pennsylvania in 1750. "On board these ships," he wrote, "the lice abound so frightfully, especially on sick people, that they can be scraped off the body." The fine-toothed combs used to rake the tiny bloodsuckers and their eggs, or nits, out of hair and beards were identical to such combs in the tombs of pharaohs and to those on the shelves of a Wal-Mart. As for body lice, well, ashore you could wash your clothes often enough to keep them under control. At sea, you could only scratch.

Or you might try crossing the equator. In 1526, seafarer Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo said, "Rarely are Christians in the New World bothered by the small pestiferous insects that grow in a man's hair and on his body. Because after we pass the line . . . all the lice on the men's heads and bodies die . . . the Spaniards are clean and little by little all vermin disappear and are not to be seen."

Vermin that did not dine on the passengers—or drop dead at the equator—dined instead on their food supplies. This was not always regarded as a bad thing. Sailors appreciated the tunnels and galleries chewed in their hardtack by a variety of invaders, lumped together under the catchall name of weevils. That made the rock-hard bread easier to chew—and the occasional weevil that came with it added a little flavor and a bit of protein. Insects, thus, had their uses.

A South American insect put the red in redcoats. Squeeze the larva of the cochineal, and your fingers run red. To colonial weavers, this was a dye to die for—brilliant, good on almost any material, and so safe you could drink it. In fact, you probably do; it is used today in all manner of foodstuffs and cosmetics.

In Mexico and Central America, Oviedo saw "many small bees about the size of flies. They do not sting or do harm. In fact, they have no stinger." Europe's bees stung, but it was a small price to pay for the honey pilfered from hives of coiled rope called "skeps." A year after the Mayflower arrived—perhaps with bees aboard—the Virginia Company of London sent beehives to its governor at Jamestown, "the preservation and encrease whereof we recommend to you." And "encrease" they did. By 1705, Virginia planter Robert Beverley could write: "Bees thrive there abundantly, and will very easily yield to the careful Huswife, two Crops of Honey in a Year." By 1782, as Thomas Jefferson wrote, "The bees have generally extended themselves into the country, a little in advance of the white settlers. The Indians therefore call them the white man's fly." When bees came, could settlers be far behind?

In some settler's lanterns glowed candles of beeswax. To a worker he might pay a wage of honey. In his cellar would likely rest a cask of methaglin, a honeyed brew that could give the sturdiest yeoman a buzz. And if her beer went flat, Martha Washington's well-thumbed copy of the Booke of Cookery told her to boil it with honey. "Nothing but honey is sweeter than money," wrote Benjamin Franklin. In time the sugar of the Indies would eclipse honey as the sweetener of choice, but until then a hive of white man's flies set many a garden corner abuzz, and honey, like the queen within, reigned supreme.

Jefferson's Notes on the State of Virginia said that "We have it from the Indians also that the common domestic fly is not originally of America, but came with the whites from Europe." If so, it was a poor hostess gift, for you never knew where it had been. Laying eggs in a dung heap? Morphing from maggot to housefly in a rat carcass? The worst of it was not what a fly bore on its feet but what it regurgitated every few minutes, a tiny droplet that it might suck up again or leave on a goodwife's soup ladle to sicken her family with dysentery, cholera, typhoid, parasitic worms, or whatever else might be flying around at the time.

Tiny midges might be flying around, too, but you would feel the bite before you saw the bug. G. H. Loskiel wrote in 1794, "The most troublesome plague ...especially in passing thro' the woods was a kind of insects called by the Indians Ponk or Living Ashes." We still call them "punkies," or "no-see-ums." Ah, sweet revenge: one kind of midge chases mosquitoes, jabs their abdomens, and sucks out the blood.

The Algonquian Indians made little distinction between these midges and other pests such as black flies and mosquitoes. All that mattered was that they bite, so one name covered the pesky lot of them: sawgimay. It translates roughly as "little flying person who bites fiercely." And how might our Declaration of Independence read today if the deputies had not hurried through its creation in order to escape the little flying persons we call stable flies that, Jefferson said, "swarmed thick and fierce, alighting on their legs and biting hard through their thin silk stockings"?

Silk comes from silkworms, and they are a picky lot. They will eat only mulberry leaves before spinning the cocoons that patient fingers have unraveled since time beyond memory to weave into a fabric of regal sheen and lordly price. That price meant profit for any sericulturist, and when mulberry trees were found growing in the New World, the race for riches was on—and soon lost. These were black mulberries; the little gourmets preferred the white mulberry. So, seeds and sprouts of the white variety were shipped over by English optimists. Laws were passed requiring all to plant them and fining any who did not. Virginia, Carolina, and especially Georgia were to be the new China, draping Old World and New in silken raiment. The Maryland Gazette of May 22, 1755, reported that in Georgia "we had great Hopes of making there great Quantities of Silk. Some has been made, and more might." More was not; the silkworms died en masse in the mid-1700s. Queen Caroline flounced proudly in her robe of Georgia silk, though rumor said hardly a thread of it came from Georgia. It was a gallant endeavor, but the hope of riches ended in rags.

Bugs beyond counting plagued and sickened our forebears, as they do us. More flies hatch in a day than there are humans on this infested planet. We have our spray cans and exterminators, but a colonist had little more than folklore and ingenuity.

He could chop up those red-capped toadstools with the white dots and soak them overnight in a bowl of milk to let hungry flies poison themselves in the morning. He could hang up a hornet's nest in his kitchen to keep out flies—and people too, no doubt. But when the hornworm chewed holes in his tobacco and the corn borer chomped his maize, all he could do was send his field hands, children included, to pick the pests off, one by one.

If he knew his ancient history, he might have done as the Romans. Pliny the Elder in the first century taught his readers that a toad nailed to a granary door would scare away weevils, and a mare's skull on a post would shoo caterpillars from a garden. Better yet, he said, get a virgin to unbind her hair and follow you topless around your garden three times, and all the caterpillars will drop to the ground. Would it work? Who would care? At least it would have cheered those itching, swatting, smarting times when the bugs were bugging the colonists.

A retired National Geographic book editor, David Robinson writes and photographs from his home in New England. He contributed "The Shot Eventually Heard 'Round the World" to the summer 2006 journal.