Page content

Ohs and Ahs, Ps and Qs:

The Art and Mystery of the Printing Office

by Edward R. Crews

In the thirty years master printer Willie Parker has demonstrated his craft to Colonial Williamsburg visitors, he’s never lost his relish for what he calls the “oh, ah” moment. It comes when the Printing Office turns a blank sheet of paper into a page full of words. “You get ohs and ahs from people every time you lift that paper off the press,” Parker said. “It’s like magic.”

Parker’s delight in the creation of that instant of insight is shared by journeyman Peter Stinely and interpreters Bill Dell, William Jones, and Jack Oblein. They work in a basement pressroom on Duke of Gloucester Street in the Historic Area. The pressroom is small and crowded with the tools of the printer’s trade-two presses, cases of type, and ink balls. Often, freshly inked pages hang to dry on lines strung across the shop. Printing lacks blacksmithing’s captivating clang, clamor, smoke, and fire. It is a quiet, undramatic craft. Nevertheless, crowds congregate. There is something irresistible about the presses.

“People like watching us work. They like to see what we’re doing, and they like to get up close. They all seem fascinated by the press and how it produces printed material. For some guests, it seems like a really ancient machine, which may be part of its appeal. But, in its own time, it was state of the art technology,” said Dell, a retired U.S. Navy pilot.

Under Parker’s guidance, everybody in the shop builds on the inherent interest visitors have in the trade to educate them about the craft and its importance in the 1700s. “Our goal is to show how printing was done in eighteenth-century Williamsburg,” he said. “We show the procedure and the products. We talk about the people who worked here. Visitors like seeing how the press operates. We hope they leave with knowledge of how newspapers, broadsides, and other printed materials were created.”

When Parker came to work at the shop in 1970, he understood little more about printing than the average visitor. Nevertheless, he knew a great deal about the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, and about cooking. Parker started working for the foundation while a high school student in the 1960s. A job at Chowning’s Tavern got him interested in the culinary arts, and he majored in food administration at Tuskegee University. Drafted soon after graduation, Parker served a tour as an Army cook. When his hitch was up, he went home and thought about rejoining Colonial Williamsburg, but he wanted a new experience. That led him to the craft program and the print shop.

It was a good fit. In three decades, the soft-spoken Parker has mastered the printer’s craft and worked his way from apprentice to journeyman to master with plenty of eighteenth-century printing knowledge to share.

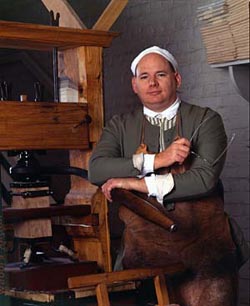

Journeyman Printer Peter Stinely at a

reconstructed colonial press. -Tom Green

To help people understand the craft as it was practiced in the 1700s, Parker often begins by discussing its origins in continental Europe during the 1400s. Until about the middle of that century, most reading material was handwritten. Production was slow and costly. Books were few, expensive, and, in general, owned by institutions or the wealthy.

About 1450, Johannes Gutenberg, a craftsman with an entrepreneurial streak, realized that business opportunities awaited anybody able to cut production costs. He developed a system of removable, reusable, and uniform metal type to use on a wooden press.

The letters of the type could be arranged-or composed-into words, locked into a form to be set on the press, and inked. Fashioned somewhat like presses used to squeeze olives or grapes, Gutenberg’s forced paper against the inky letters, transferring their images. It was thus possible to strike inexpensive multiple copies. When a job was done, the type was removed from the form and sorted for storage by letter until it was time to compose a different pamphlet or book.

The printing press reduced the cost of books, increased their availability, and encouraged the spread of literacy. It helped alter the economic, scientific, social, and ideological outlooks for the next five centuries. It did little for its inventor, however. He died in poverty.

Working in the print shop are, left to right, Journeyman Printer Peter Stinely at the typebox, Master Printer Willie Parker with the paten, and Interpreter Chadwick Jones with the ink balls. - Barbara Temple

“During 300 years, there was little change in the technology,” Parker said. “For example, type was set by hand throughout this period. Gutenberg could have walked into an eighteenth-century shop and felt quite comfortable.”

Like all 1700s crafts, printing required an apprenticeship. A printer’s apprentice had much to learn, but the basics were simple. To start: Select the letters from the storage case, arrange them in backward words and lines as they would appear on a page in reverse, lock them into place with an iron frame called the “chase,” and put them on the press.

Press operation usually required two men-a beater and a puller. The beater put ink on the type using two balls made of animal skin and stuffing and covered with ink. The press used a moveable, flat horizontal surface, a platen, to press the paper evenly against the type. The puller put the paper on points, which held it steady. A small bar and a worm screw controlled the platen, beneath which paper and type were positioned. The puller pulled the lever that operated the worm screw, which moved the platen downward to press paper against the inked type.

An efficient beater-puller team might produce 180 to 240 printed sheets an hour. This work was taxing. Days could run fourteen hours. The more demanding of the two jobs was the beater’s, Dell said. Putting ink on the type required vigorous use of the ink balls. A beater easily worked up a big sweat in a small time. Many Southern printers used slaves on the press, Parker said.

An apprentice learned early that printing was part science and part art. He was taught to space letters and lines so they were attractive and easy to read. He couldn’t apply too much ink to the type. If he did, the letters would blur.

There are conflicting theories about the origins of the phrase “minding your Ps and Qs.” One is that it dates to the eighteenth century, when, at a glance, the lowercase types of those letters, castlike all type in reverse, might easily be confused.

“Typesetting is not difficult, but it is boring,” Dell said. “You pull each letter individually from the case as you need it. Even if somebody is really good at this, it can take twelve to fourteen hours to set two newspaper pages. All that time you’re standing on your feet.”

In the bindery shop, are, left to right, Interpreter Addison “Brown” Evans, Master Bookbinder, Bruce Plumley, and Journeyman Bookbinder Dale Dippre. - Barbara Temple

Parker said, “You can tell when you look at a piece of 1700s printing just how good the printer was. Some were meticulous; some were slipshod. You can look at a piece and determine what kind of a master might have been in charge.”

A print-shop owner needed funds for supplies and equipment, as well as business sense. “Printing was expensive,” Parker said. “A master printer needed to buy paper, ink, a press, and type. That took money. He also needed to be in a location where he could make money, a place with a lot of people and a need for printed material.”

A talented printer might develop an eye for attractive layout, design, and typography and, on rare occasions, develop literary skills. Benjamin Franklin, the most famous American printer of the period, was an accomplished writer and publisher. He learned the craft as a teenager and maintained a lifelong pride in his printing skills. Franklin, however, was exceptional. Most printers in Great Britain and America set into type only what others brought them, Parker said.

Before the Revolutionary War, most large printed works came from Great Britain. There, big printing operations in major population and educational centers produced Bibles, dictionaries, novels, reproductions of classics, and how-to books. London boasted a daily newspaper by 1702.

In America, however, most people lived on farms, and there were few urban markets to support large printing operations. The colonies did need some printing, however.

By Virginia standards, Williamsburg was a good printing market. There were public documents to duplicate in the capital-laws, proclamations, currency, bonds, and indentures. Churches needed broadsides and sermons. The colony needed a newspaper. Other clients required playbills, auction notices, tickets, ledgers, account books, and business forms. The College of William and Mary needed forms. Like most books, the texts the students used came from abroad, but books were printed in Williamsburg as well.

During the colonial period, Williamsburg was home to at least twelve master printers. Best known was William Parks, an energetic businessman, who came to Williamsburg about 1730 and eventually opened a shop on Duke of Gloucester Street. He was the public printer of Virginia, charged with the job of reproducing the acts of the General Assembly. He also did a lot of work for businesses. In 1736, Parks founded the Virginia Gazette, the first newspaper in the colony, and promised to deliver the “freshest Advices, Foreign and Domestick.”

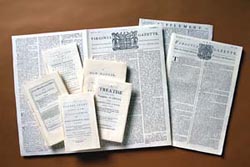

These reproduction printings example some of the more popular pieces to come from the eighteenth-century Williamsburg press. Newspapers, political pamphlets, almanacs, treatises, and tracts all fed the public’s appetite for inexpensive reading material, and created a community of theories, ideas, and arguments. - Tom Green

Besides his printing business, Parks operated a post office in his shop and sold paper products from other establishments, including writing paper, books, and newspapers, some of which came from London. Parks also tried his hand at papermaking. In 1743, he started the town’s only paper mill. Franklin offered advice and encouragement for this venture and purchased paper from it.

Clementina Rind was Virginia’s first female newspaper editor. She took over her husband’s printing business, which included the newspaper they had founded, after his death in 1773. She also was printer to the House of Burgesses.

Williamsburg’s printing market, however, shrank in 1780, when the government moved to Richmond. The printers followed.

Today, Colonial Williamsburg’s Printing Office, Post Office, and Bookbindery complex keeps alive the traditions of the colonial craftsmen. The shops like to tackle projects that expand the skills of today’s Williamsburg printers. One of the most popular has been a reprinting of Every Man his own Doctor; or, The Poor Planter’s Physician.

Parks printed the seventy-two-page book in 1736. It is a heal-thyself guide to curing diseases ranging from whooping cough to a sore throat. The reproduction is as an example of the eighteenth-century printer’s craft and is the shop’s best-seller. Parker, though grateful for its popularity, is a little puzzled by its steady appeal. Another reliable, but not quite as popular, title is Treatise on the Propagation of Sheep.

These days the shop is printing versions of three mastheads that appeared successively in Alexander Purdie’s Virginia Gazette during the spring of 1776. They show graphically the Virginia colony’s growing sense of independence from Great Britain. The first was in use early in May 1776. Its centerpiece is the coat of arms for the Royal Colony of Virginia. The second was used in mid-May, following the adoption of the Virginia Resolution to declare the United Colonies free and independent states, absolved from all allegiance to or dependence upon the crown or Parliament of Great Britain. This masthead centerpiece is text in a box that reads “Thirteen United Colonies-United We Stand, Divided We Fall.” By early June, a new coat of arms bore the motto “Don’t Tread on Me.” The purpose of the reprints is to show people not only how a printer worked, but how the press reflected popular opinion and current events.

Parker finds it interesting that during the past thirty years, while teaching so many visitors about the trade and its role in colonial society, his pupils so often have had the same questions.

Many wonder about the “ƒ” that appeared in eighteenth-century books and newspapers. Parker said it was a holdover from handwritten material. The “ƒ” was used at the beginning and middle of a word, but not at the end. Printers gave it up about 1800.

Why didn’t printers have common words like “the” and “of” cast in type? Because, Parker said, if a letter in a cast word was damaged, the whole word was useless. If one letter of type was damaged, a printer lost only one letter.

Many visitors too are surprised to learn that eighteenth-century paper was made from rags. Paper from wood pulp didn’t come into common use until the 1840s.

Nearing retirement, Parker glimpsed into the shop’s future. “As far as I can see,” he said, “things will pretty much continue like they are now.” He anticipates that Colonial Williamsburg’s printers will keep setting type and printing books, newspapers, and pamphlets, and collecting all those “ohs and ahs.”

Ed Crews contributed to the summer journal a story on witch bottles, hidden shoes, amulets, and charms.