Castles, Factories, and Forts

Though 12.5 million individuals were forced onto European slave ships in African ports, thousands—perhaps millions—more did not survive the journey to the castles, forts, and trading stations that supplied slave ships on the Atlantic coast. African victims of European and African slave traders experienced the violent loss of community, culture, and life, while coastal traders who allied themselves with European slavers gained power and prestige as recipients of desirable trade goods and weapons.

European powers arranged treaties with coastal African leaders, who allowed European traders to establish small, often well-defended centers of trade in strategic locations. The presence of these European beachheads greatly affected the settlement patterns, demographics, and trade routes associated with such African coastal towns.

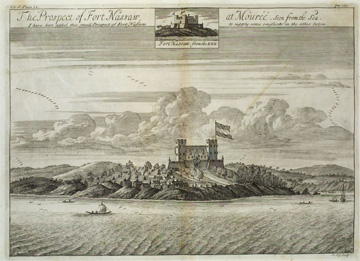

In some areas along the West African coast, especially on the Gold Coast, the Portuguese, Dutch, and British constructed dozens of forts and other substantial structures (often referred to as castles), whose imposing presence meant to symbolize and promote European wealth and prestige. From positions high above the shoreline, cannon were faced toward the sea, to ward off ships from rival European trading powers.

Europeans hoped that such forts and castles, and the reciprocal relationships that maintained their presence, would establish mini-monopolies, whereby the coastal trade in slaves in particular regions could be cornered, at the exclusion of other European traders. In practice, however, African leaders sought to play off the interests and necessities of competing European traders for the best possible exchange for their captives.

In most areas of West and Central Africa, Europeans negotiated with locals to construct so-called factories, or trading houses, in which factors, or employees of European trading firms, managed the purchase of captives from middlemen who linked coastal traders to vast slaving frontiers in the interior. As with other forms of European trading establishments, each factory was a kind of world unto itself, as European and African peoples formed a wide range of complicated relationships that spawned new trade languages, new cultures, and families of mixed parentage. Along the African coast, however, pidgin languages that facilitated trade arose from the sixteenth century onward. Often, such languages reflected the creole identities of their speakers and combined words and concepts from a variety of European and African languages in ever-changing ways.

From the shadows of coastal forts, castles, and factories, captives were loaded by small vessels, often pirogues, onto slave ships anchored off shore. In some cases, European traders sailed from factory to factory, acquiring small numbers of slaves at each point until their vessels hit capacity. In other cases, European traders filled their ships by negotiating a single purchase of hundreds of captives from one location.

History & Memory

Related Pages:

-

Logbook of the Bordeaux slaver Le Patriote

Logbook of the Bordeaux slaver Le Patriote

-

Slave History Museum, Calabar

Slave History Museum, Calabar

-

Final slave exit from the Cape Coast Castle

Final slave exit from the Cape Coast Castle

-

Olaudah Equiano

Olaudah Equiano

-

Gold Coast

Gold Coast