Slavery Remembered

How do societies remember? How do they forget?

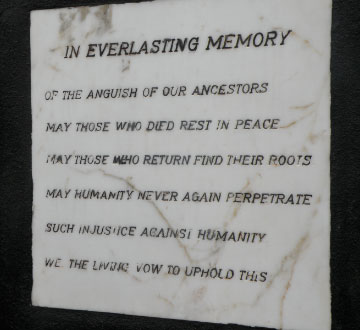

Long neglected as serious subjects of study by professional historians and curators, the topics of slavery, slave trade, and their legacies have until the mid-twentieth century largely belonged to the realm of historical memory—preserved, commemorated, and remembered by individuals and communities through art, the written and spoken word, ceremonies, sites, and markers inscribed upon the landscape and the human spirit.

In the past two decades, governments, institutions, and cultural heritage professionals across the globe have also turned their gaze and inquiry—in many cases for the first time—to slavery, slave trade, and the worlds they made. As a result, there is increasing interest in understanding how societies remember, enshrine, or commemorate some aspects of the past, and overlook or deliberately silence others.

Where official narratives, monuments, and representations of slavery and slave trade have been absent or inadequate, individuals and groups engaged in memory work continue to remind us of a shared past that contains important lessons for our time. Increasingly, professionals are accessing and examining collective and cultural memory in an effort to break historical silence on these subjects and to make their legacies more visible to a broader public.

Many today (including those working or volunteering at sites, museums, and community organizations featured on this website) are driven by questions that challenge us to find connections between past and present: How do forms of historical slavery relate to us today? What do 366 years of transatlantic slave trading have to do with our modern world? Why examine a past that raises challenging, perhaps even painful, questions?

It is one of the great ironies of history that many of the world’s architectural wonders, lasting institutions, and governing bodies exist because of profitable relationships to slavery or slave trade in the past. Charming cityscapes, impressive centers of learning, and inspired notions of law and liberty are among the many legacies of a kind of Atlantic “ugly beauty,” in the words of poet Robert Earle Price, that we have inherited. The beauty, perhaps, we can admire in its own right. But the ugliness too requires its own understanding, and to this end—in Africa, Europe, and the Americas—a renaissance of reckoning is underway.

History & Memory

Related Pages:

-

Middle Passage Ceremonies and Port Markers Project

Middle Passage Ceremonies and Port Markers Project

-

Periwinkle Initiative

Periwinkle Initiative

-

Ku Klux Klan outfit

Ku Klux Klan outfit

-

Nanny

Nanny

-

Cape Coast Castle

Cape Coast Castle