British Slave Trade

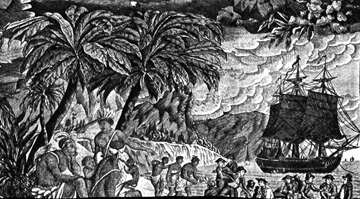

The British rose to slave-trading prominence in the seventeenth century, overshadowing in complexity and scale the participation of all other Northern European powers in the transatlantic trade. All told, British ports outfitted nearly one-third of all transatlantic slave voyages, transporting almost one million Africans to Jamaica and almost half a million to the small island of Barbados before ruling the trade illegal in 1807. Slave trading proved essential to the political, economic, and diplomatic success of the British empire.

Constant changes in organization and direction of the British slave trade demonstrate an important fact about the transatlantic slave trade over its 366 year history: it operated like a protean monster, ever-shifting the direction and reach of its massive, far-flung tentacles. Having transported 3,400 African captives to the Caribbean between 1501 and 1641, an increasingly complex commercial system underpinned a transformation in the British trade in the mid-seventeenth century. Behind each slaving voyage outfitted in London, Bristol, and Liverpool lay an intricate network of economic ties. Ships were often financed by a group of investors who met at places like the Jamaican Coffeehouse in London. Goods loaded onto ships destined for West Africa were acquired, often on credit, from manufacturers and merchants in distant towns and regions.

Indeed, the entire Atlantic economic system was lubricated by an international system of credit, in which British investors and banking houses played a major role. Bills of credit became the means of financing this global system because there were huge time lags involved. Slave ships were away from their home port for a year or more. Planters dispatching sugar to London, or tobacco to Glasgow, had to wait long periods for payment for their produce. Credit, financed from the major centers of banking, and insurance for each ship (and for the African captives on board) all reflected the increasing commercial complexity of the seventeenth—and eighteenth—century Atlantic economy.

British merchants, and the captains of their slave ships, developed contacts in Africa and in the Americas. They learned what sorts of goods were preferred by particular African traders and knew which agents or planters in which American colony could be relied on for the best sale and deal. Slave-ship captains were entrusted with valuable vessels and cargoes and were expected to use discretion and experience to provide profits for the enterprise’s investors. Indeed, the merchants behind the trade realized the importance of their captains, and paid them accordingly (both in wages and in bonuses for a successful trip).

By the time Britain abolished the transatlantic slave trade, beginning in 1807, British investors, insurance companies, and banking houses—as well as sailors—had facilitated voyages that tight-packed more than 3.2 million Africans for a Middle Passage, whose survivors helped realize a profitable and powerful British New World.

History & Memory

Related Pages:

-

Bridgetown, Barbados

Bridgetown, Barbados

-

Transatlantic Slave Trade

Transatlantic Slave Trade

-

List of enslaved men

List of enslaved men

-

1811 Slave Revolt Memorial

1811 Slave Revolt Memorial

-

Museum of London Docklands

Museum of London Docklands