Page content

The Colonial Williamsburg Gardens

Colonial Williamsburg's gardens are the result of a notable union of materials: evergreen shrubs, especially boxwood, and the various colors and shapes of brick, as seen here in “brickbat paving,” an antique form of paving that made use of the inevitable accumulation of broken bricks at a colonial house or commercial site. This union of green with the permutations of red brick gives The Revolutionary City a unity of elements, and infinite garden compositions can be made via the use of these timeless materials.

Arthur Shurcliff, left, was the original and principal landscape architect during the earliest years of the Restoration. Alden Hopkins, right, was a deputy to Mr. Shurcliff and in subsequent years went on to assume primary responsibility for the development of Colonial Williamsburg's collection of gardens. "Colonial Revival" is the term that was developed to describe the style of garden design that developed over the course of the early 20th century, a style hugely defined by the work of Arthur Shurcliff and Alden Hopkins.

Detail of Mr. Meys Garden from "Charleston Garden Plats" by Emma B. Richardson, Charleston Museum Leaflet no. 19.

Courtesy of The Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina.

Arthur Shurcliff, in fact, was one of the earliest pioneers of the development of the Colonial Revival style and his study of old maps and surviving examples of authentic colonial gardens meant that Williamsburg's gardens would reflect the scale, organization, and geometric playfulness of mid- to late-Georgian gardens of colonial America.

Arthur Shurcliff traveled throughout the American South and England gathering the ideas that would lead him to create in Williamsburg a collection of gardens cited as one of the world’s ten most important gardening sites.

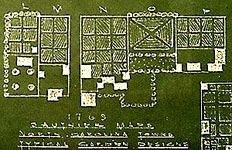

Among other sources Arthur Shurcliff used were 1769 maps of North Carolina towns that detailed the garden layouts of the towns' houses. Made by French cartographer, Claude Joseph Sauthier, these maps and their amazingly detailed garden sketches (right) allowed later historians to confirm that Georgian artistic principles of symmetry and formality were understood and used in Colonial America.

The Sauthier maps, along with others, such as the map detailing the Charleston, South Carolina lot and garden layouts (right), were invaluable in giving the early landscape architects precedents on which to base their compelling designs. The David Morton garden in Williamsburg is very reminiscent of the planting bed detail of the garden to the right with its arrangement of four clipped planting beds surrounding a fifth element in the center.

Sauthier maps as redrawn by Alden Hopkins

Courtesy of The Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina.

Although 18th-century taste tended to emphasize formality and symmetry in landscape design and the layout of cities, the 18th century also reveled in the artistic contributions that Nature and natural forms offered connoisseurs, as in the soup tureen that mimics the texture and color of melons and melon vines, and the coffeepot with its vegetative leaves and pineapple textured body.

18th century soup tureen, ca. 1765. Cream colored earthenware with colored glazes. CWF collection.

18th century coffee pot, ca. 1765. Cream colored earthenware with colored glazes. CWF collection.

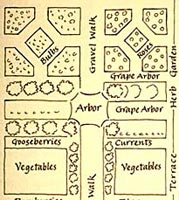

So, garden design in the 18th century, and during the period of the early 20th century when the Colonial Revival style was developing, relied on formal regularity, as seen in the garden plan (left), but softened and relieved by the innate, less regular, organic forms of plants, as in the Cherokee rose (right).

Miss Lucy Pegram Blow's Copy Sketch of Benjamin Waller Garden Design at Tower Hill, Sussex County, Virginia. Courtesy of The College of William and Mary

Cherokee rose

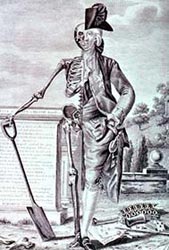

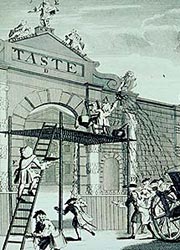

In the aesthetically charged atmosphere of aristocratic England and gentry colonial Virginia, gentlemen of leisure competed with each other via the expression of Taste, that nebulous collection of choices and preferences reflective of one's innate or acquired artistic sensibilities. One's taste in landscape gardening was part of the package that helped to define one's position in a tiered society of wealth and status. But, that competitive tendency to use taste as a social arbiter was simultaneously lampooned at the time, as depicted in the 18th-century prints below.

Detail, Life and Death contracted... engraver unknown, England, c. 1760, black-and-white line engraving, 1962-2941,1.

Detail, Taste, or Burlington Gate, Engraved by William Hogarth, London, Jan. 15, 1731/2, black-and-white line engraving, 1972-409,39.