Page content

Online Extras

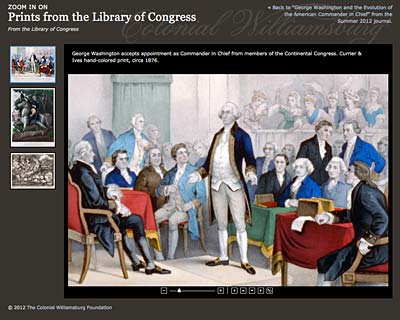

Zoom in on Prints from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress

President Thomas Jefferson did not ask Congress's approval before sending troops against the Barbary pirates. As commander in chief, he believed he had the constitutional authority for military aciton to protect the nation’s interests.

Library of Congress

A British print mocks James Madison during the War of 1812. He had, ineffectively, assumed control of artillery before Washington fell.

Library of Congress

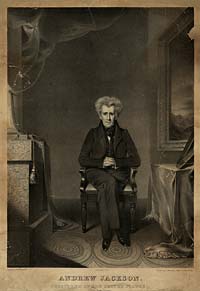

As commander in chief, Andrew Jackson directed or threatened military force against eastern Indians and South Carolina.

Library of Congress

During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln appointed and fired generals and visited battlefields to help direct the course of war.

George Washington and the Evolution of the American Commander in Chief

by Christopher Geist

The commander in chief, the president, dispatched special forces across the globe to eliminate a threat to our national security. Because it was a defensive response to attacks on United States interests, he said there was no need to inform Congress until after the mission ended. That is what he did.

Although the scenario describes President Barack Obama's use of Navy Seals against Osama Bin Laden in 2011, it also summarizes Thomas Jefferson's use of naval and marine forces against the Barbary pirates in 1801. Each exercised the independent powers of the executive in the constitutional capacity of commander in chief, powers now well defined and greater than the Constitution's framers intended.

Considering the importance and potential impact of the position, the Constitution's description of the president's military role is remarkably terse: "The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States." The powers of declaring war and financing the armed forces are given to Congress, but the president is in command. The details of implementation are left to posterity to puzzle out and develop as conditions warrant.

The idea that a civilian should control the military was critical in the debates that created the Union. One of the Declaration of Independence's grievances against George III was that his government had rendered "the military independent of, and superior to, the civil power." Earlier, on May 15, 1776, the Virginia Convention asserted in the Virginia Declaration of Rights the primacy of civilian control: "In all cases the military should be under strict subordination to, and governed by, the civil power." The federal president would be not a part of the military but an elected civilian with supreme power over it.

Even so, there were concerns. With so much power in the hands of an individual, was it not possible that a despotically inclined leader might misuse it? In the words of Patrick Henry, "How easy is it for him to render himself absolute! . . . Can he not, at the head of his army, beat down every opposition?" Another Virginian, George Mason, said it would be dangerous to permit the president to lead an armed force into the field, since "without any restraint" there was the possibility "he might make bad use" of the military. South Carolinian Eldridge Gerry asked whether an unscrupulous chief executive would use his military to suppress dissent.

The commander in chief clause was prominent in the Federalist Papers, especially Number 69, written by Alexander Hamilton, aide-de-camp to George Washington during the Revolutionary War. Comparing the military power vested in the president with that of the king of Great Britain, Hamilton said that the president's powers were limited and tempered by those powers vested in the legislative branch: "The President will have only the occasional command of such part of the militia of the nation, as by legislative provision may be called into the actual service of the Union." The king of Great Britain, on the other hand, exerted such command over the military at all times. The president's military power

would amount to nothing more than the supreme command and direction of the military and naval forces, as first General and Admiral of the confederacy: while that of the British King extends to the declaring of war and to the raising and regulating of fleets and armies; all which by the Constitution under consideration would appertain to the Legislature. . . .

The President of the United States would be an officer elected by the people for four years. The King of Great Britain is a perpetual and hereditary prince. . . .

What answer shall we give to those who would persuade us that things so unlike resemble each other? The same that ought to be given to those who tell us, that a government, the whole power of which would be in the hands of the elective and periodical servants of the people, is an aristocracy, a monarchy, and a despotism.

During the Constitutional Convention in the summer of 1787 and throughout the ratification process, there was little doubt about the identity of the first president and commander in chief. As the delegates considered the commander in chief clause, the silent but dominant figure in the room was George Washington. After his brief acceptance speech acknowledging his selection as presiding officer, he did not participate in the debates, but served as convention president. It may be that the inevitability of Washington's presidency more than any other factor ensured the ratification of the Constitution.

By the time General Washington reached Williamsburg in the autumn of 1781 to plan the Yorktown campaign, no other person in the world knew what it was to be a commander in chief and subordinate to a civilian authority. George Wythe's house on Palace Green was Washington's headquarters as he developed strategy in concert with French commander Comte Jean Baptiste de Rochambeau. Since his June 1775 appointment to the post by Congress, Washington had more or less invented the rank of commander in chief.

According to British historian Marcus Cunliffe:

The limits of his authority could not be exactly defined, in a situation without precedent. Even if a precise definition could have been formulated, much else would have remained hazy. He had a large but vague jurisdiction. . . . Washington was clearly senior in rank to all the other generals. But what control was he to exercise, theoretically or actually, over armies that might be several hundred miles away from his own headquarters? To what extent could he give orders to the French military and naval leaders when their expeditions began to arrive in 1778? Who was to formulate strategy?

More critical was the question of where Washington stood in relationship to "the governors of the states, other commanders, the President of Congress, and the Board of War." Could these or any other entity remove him from command?

Washington addressed each of these issues as the war progressed. He helped to direct military operations throughout the American theater, sometimes moving troops of his own to assist distant armies under other commanders. In some instances, those commanders wished to replace Washington as commander in chief. In concert with his subordinates and French allies, he asserted steady leadership in the closing acts of the war. As Cunliffe wrote, "At a vital moment he seized the initiative, like an ideal coalition leader, in ensuring that he and the French for once acted in entire harmony." The result was Cornwallis's surrender at Yorktown.

Washington's relationship with the Congress was stormy, but it demonstrated his acceptance of civilian control of the military. Repeatedly, he pleaded for support for his forces, and almost as often his requests were met with indifference. He wrote to Congress on behalf of "Our sick naked, our well naked, our unfortunate men in captivity naked." Congress's response: "Last war, soldiers supplied their own clothing." From Morristown in May 1780 Washington wrote, "It is with infinite pain that I inform Congress that we are reduced again to a situation of extremity for want of meat." There was no satisfactory reply. Gunpowder, medicine, tents, barracks, and, most frequently, funds to pay the troops were also lacking.

Historian Catherine Bowen refers to Washington's wartime dispatches to Congress as "hot with anger and indignation." Yet he remained loyally subordinate to the civilian authority. There were those who had supposed, even hoped, that the commander in chief would seize power and become the nation's first king. Instead, when hostilities concluded and the treaty was signed, he bade farewell to his troops and slipped off to Mount Vernon. "He made it plain beyond doubt," wrote Cunliffe, "that he cherished no overweening dream of military dictatorship."

Thus, when Washington was sworn in as president he had already established military subordination to civilian authority, and during his presidency he conducted himself accordingly as commander in chief. Three times from 1791 through 1794, he ordered troops to campaign against hostile native forces north of the Ohio River. He offered general plans about how the armies should proceed, selected a site near present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana, as a primary garrison, and appointed the commanding officers. In addition to fighting the Miami and Wabash Indians, these campaigns asserted United States' sovereignty over the Ohio territory in the face of British military posts in the vicinity maintained in violation of the treaty that ended the Revolution. All of this was accomplished without declarations of war from the Congress.

The commander in chief had many things on his mind in 1794. Farmers and distillers in western Pennsylvania not only refused to pay a new excise tax on spirits but tarred and feathered federal tax collectors and began organizing troops to resist the government's authority. Using his constitutional authority to call out the militia, President Washington assembled a force of more than 12,000 to march on the Whiskey Rebellion insurrectionists. He donned his old uniform and went into the field. "I have visited the places of general rendezvous," he reported to Congress, "to obtain more exact information, and to direct a plan for ulterior movements." He reviewed the forces and with "every appearance assuring such an issue as will redound to the reputation and strength of the United States, I have judged it most proper to resume my duties at the seat of government." Washington left his trusted friend and governor of Virginia, "Light Horse" Harry Lee, in command, and the rebellion was quelled within weeks. According to historian Joseph Ellis, this would be the "first and only time a sitting American president led troops in the field."

Washington's presidency and his years as commander in chief during the Revolution established the tradition of civilian leadership of American armed forces. Succeeding chief executives would continue that tradition even as they strengthened the powers and reach of the commander in chief. James Madison briefly took control of artillery units in defense of Washington, DC, during the War of 1812. By all accounts he did poorly, but the incident is another instance of a president being on the battlefield during an engagement. Andrew Jackson invoked his role as commander in chief to rationalize the removal of the eastern Indians, and he threatened armed force against South Carolina during the tariff crisis in 1832.

Abraham Lincoln used massive military force to defeat the Confederacy. He also directly appointed and relieved more military commanders than perhaps any other president. And Lincoln, although never in uniform, frequently visited the field to confer with and offer strategic advice to his generals. Perhaps most notably, his office as commander in chief provided his rationale for his wartime suspension of habeas corpus and the Emancipation Proclamation.

Of all the military actions mentioned above, one, the War of 1812, was under a declaration of war from Congress. Five times has the Congress declared the United States to be in a state of war. That does not mean that United States armed forces have so infrequently seen battle. American history is littered with conflicts known by almost any designation but "war." Police action. Raid. Intervention. Conflict. No fly zones. Incursion. Rescue mission. Naval blockade. American men and women have fought in Indian wars, in Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan. They have been deployed against a Panamanian dictator, Somali pirates, and in Mogadishu, Somalia, and in Yugoslavia. In no case was war declared.

Although Congress has the power under the Constitution to declare war, raise troops, and control military funding, presidents long ago began to assert their presumed right to commit troops to "defend and protect" the nation and its interests. Citing their constitutional role as commander in chief, presidents have used the armed forces more than two hundred times outside the United States.

In the face of two major undeclared wars—there is really no other appropriate word for the conflicts in Korea and Vietnam—in the course of two decades Congress passed the War Powers Resolution of 1973 over President Richard Nixon's veto. The resolution requires the president to notify Congress within forty-eight hours of deployment of military forces and requires that they begin to be withdrawn in ninety days unless Congress declares war or offers some other form of specific authorization. Presidents have routinely ignored the act, and Congress has just as routinely protested and attempted to assert its authority. One wonders where Washington would have stood on this constitutional struggle. It seems certain, however, that he would agree the commander in chief clause of the Constitution has made the president of the United States the most powerful civilian in the world.

Christopher Geist, professor emeritus at Ohio’s Bowling Green State University, contributed the story “The Purposes of Historic Preservation” to the autumn 2010 journal.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Louis Fisher, Presidential War Power (Lawrence, KS, 1995).

- Warren W. Hassler Jr., The President as Commander in Chief (Menlo Park, CA, 1971).

- William Hogeland, The Whiskey Rebellion (New York, 2006).

- Peter Irons, War Powers. New York, 2005.