Page content

Johnny

- Enslaved waiting man owned by Peyton Randolph

- Bequeathed to Edmund Randolph on Peyton Randolph’s death

- Estate inventory value of £100 reflects high worth

- Ran away in 1777; never apprehended

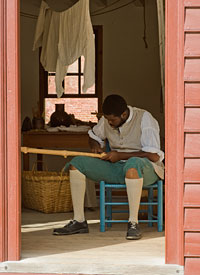

Johnny was a house slave who worked as Peyton Randolph’s waiting man in the 1760s. Records of the errands he ran show that he bought sealing wax and paper at the Printing Office in 1764 and 1765. He received a tip of £0.3.9 from William Marshman, Governor Botetourt's butler, in April 1769. Marshman referred to Johnny as the “Speaker’s Man,” a clear indication that Johnny served as Randolph’s waiting man by 1769.

Randolph took his “man Johnny” and an enslaved boy with him when he traveled to Philadelphia to attend the Continental Congress in August 1775. Johnny probably accompanied Randolph on all of his trips. Johnny ran errands and waited on his master there until Randolph died in Philadelphia on October 22, 1775.

Five days after Randolph’s death, Johnny, still in Philadelphia, ran an errand for Thomas Jefferson and received a tip from him of seven shillings and six pence. Johnny probably returned to Williamsburg with Betty Randolph following the Speaker’s funeral.

Peyton Randolph bequeathed Johnny to his nephew, Edmund Randolph. Johnny’s high value of £100 in the January 5, 1776 inventory of Randolph's estate in York County indicates the importance of his position as Randolph’s waiting man.

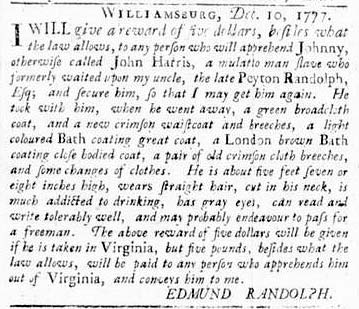

The following winter, in December 1777, Johnny ran away from his new master. Edmund Randolph offered a reward for his return. He placed a runaway ad in the Virginia Gazette:

Virginia Gazette, Purdie, ed., 12 December 1777, page 3, column 1.

View plain text advertisement

I will give a reward of five dollars, besides what the law allows, to any person who will apprehend Johnny, otherwise called John Harris, a mulatto man slave who formerly waited upon my uncle, the late Peyton Randolph, Esq; and secure him, so that I may get him again. He took with him, when he went away, a green broadcloth coat, and a new crimson waistcoat and breeches, a light coloured Bath coating great coat, a London brown bath coathing close bodied coat, a pair of old crimson cloth breeches, and some changes of clothes. He is about five feet seven or eight inches high, wears straight hair, cut in his neck, is much addicted to drinking, has grey eyes, can read and write tolerably well, and may probably endeavour to pass for a freeman. The above reward of five dollars will be given if he is taken in Virginia, but five pounds, besides what the law allows, will be paid to any person who apprehends him out of Virginia, and conveys him to me.

The fact that the younger Randolph mentioned a reward to anyone who found Johnny in a place other than Virginia suggests that he believed that Johnny might try to leave the state. The trip that Johnny took to Philadelphia in 1775 exposed him to life in the largest city in North America – a city with a large, thriving free black population. It is possible that Johnny returned to Philadelphia to renew contacts with friends and to try to pass as a free man, perhaps under the name John Harris.

There is no evidence that Edmund Randolph regained possession of Johnny.