Page content

Williamsburg's Long Christmas

by Michael Olmert

Photos by Dave Doody

Historically, two threads run through Christmas celebrations: piety and pleasure.

The Reverend James Blair, founder of the College of William and Mary, was awakened about midnight two weeks before Christmas 1702 by the sound of "great nails," as he called them, being pounded in "to fasten and barricade the doors of the Grammar School."

Plainly, Christmas cheer was about to overflow once again in Williamsburg, capital of the Virginia colony. For this was the English schoolboy custom of "barring out" the teachers, a ceremonial lockout that signaled the start of a month of Christmas jollity, a tradition more profane than sacred. The hammering surprised Blair, he said, because that very custom had been outlawed at the school years earlier. Silly man.

The Reverend James Blair finds himself on the wrong side of the student Christmas prank of "barring out." B. J. Pryor as Blair looks out on the fractious young men, from left, Daniel Cross, Marley Brown, and Arthur Schechter.

As Blair was forcing his way inside the school, his notions of youthful innocence began to go pear shaped. While he was breaking in, he said, the students

presently fired off 3 or 4 Pistols & hurt one of my servants in the eye with a wadd as I suppose of one of the Pistols, while I press'd forward, some of the boys, having a great kindness for me, call'd out "for God's sake sir don't offer to come in, for we have shot, & shall certainly fire at any one that first enters."

Season's greetings.

So much for Christmas as a time of reverential, unalloyed goodwill. But that's what you get when you come to consider the nature of Christmas at Williamsburg. It's sacred and profane, in the way Christmas has been since the earliest Middle Ages.

Overall, for eighteenth-century Virginians, Christmas was more holy day than holiday. Churchgoing was what most people did—though Robert Carter of Nomini Hall pointedly stayed home when his family went off to the Christmas service in December 1773. The congregation was so sparse that day the vicar "thought it improper" to administer the Eucharist.

The devotional side was far outweighed by the balls, fox hunts, horse races, sumptuous dinners, the firing of guns, and, yes, the barring out of teachers. At The Cliffs, the Fauntleroy family manor house in Westmoreland County, the tutor was ceremonially barred out of his classroom by his students December 13, 1773. School would not resume until after January 6, Twelfth Night.

Which brings us back to the staggering reality of Christmas past. It lasted a long time.

Whoever found the bean in the Twelfth Night cake was crowned King of the Bean. Custom dictated that the youngest child cut the cake and serve the slices. From left, Rachel Harcourt, the lucky royal ruler of the bean, Allison Harcourt, Patrick Andrews, Martin Harcourt, and Dennis Watson.

Christmas was never a one-day event, but gradually became a protracted series of devotions, services, feasts, games, and entertainments. The whole, of course, was driven by the birth of Jesus. For a practicing Christian, there was scarcely a more joyous moment, the day forecast by scripture. But play overcame devotion. The burgeoning festivities needed more than just a day.

In its grandest medieval version, the Christmas season lasted two months, from the first Sunday in Advent, at the beginning of December, to the feast of the Purification of the Virgin Mary, also known as Candlemas, February 2. Most of the celebrating and feasting during this period was only faintly associated with religious observances, none of which were considered as serious doctrinally as December 25. Most observances were chiefly secular, offering a winter respite to a mainly agricultural workforce whose minds and legs were usually dangling a bit in the quiet and dark winter months.

That was the theory anyway. Predictably, some complained, as an English writer in 1631 did, fed up with the Twelve Days of Christmas and its incessant, windy music. It is, said he:

an ill wind that begins to blow upon Christmasse Eve, and so continues, very lowd and blustring, all the twelve dayes: or an airy meteor, composed of flatuous matter, that then appeares, and vanisheth, to the great peace of the whole family, the thirteenth day.

The Twelve Days were just the centerpiece of a season that ran from December 25 to the Epiphany, January 6. This was an amalgam of feasts or saints' days, some of which came before Christmas: St. Nicholas Day, December 6; St. Lucy's Day, the feast of lights, December 13; Christmas; St. Stephen's Day, December 26, also called Boxing Day; the Feast of the Holy Innocents, also known as Childermas, December 28; the Feast of the Circumcision, January 1; and the Epiphany, or the showing of the Infant to the Magi, January 6.

Three ancient traditions are fused into the idea of Christmas, and only one of them is Christian. The earliest is tied to the winter solstice and the importance of ensuring the sun's return for another fertile spring. This custom was added to by the Romans, who created a week-long Saturnalia, a new year's festival in honor of their god Saturn, the sower of seeds. A final layer of meaning was added by medieval Christianity, which regularly saw its attempts at biblical cheer descend into uproar. All of which led, in time, to those lads shooting at Blair in 1702.

The profane elbowed aside the sacred at many Yuletide celebrations. This English broadside from 1794 anatomizes a fractured gathering around the Twelfth Night cake. "Square Toes" in the center thinks his draw of "cuckold" a fine joke, but his wife is fleshing out the prophecy with her young lover.

To prehistoric man, winter was the all-too-obvious end to the agricultural year. People throughout the Northern Hemisphere annually noted the sun's slow but inexorable slide southward each autumn. Something had to be done lest the sun keep going south forever, a chilling thought.

Since the sun was obviously a vast fire in the sky, perhaps it could be induced to return by great bonfires. Sure enough, every day the sun dives lower and lower toward the horizon until December 21, where it stands still, the solsticium in Latin. There, it notices all the earthly bonfires and grudgingly begins to return to its chastened and newly reverent devotees.

The return of the light and life-giving heat is the key. For centuries, the Advent wreaths of Christianity were lighted with four candles, one for each of the four weeks before Christmas day. Similarly, the medieval Yule log was burned a little each day to preserve its light for the Christmas season. A tiny bit would be salvaged to spark the next year's Yule fire. And Scandinavians center their midwinter revelry on the feast of St. Lucy's Day, another festival of lights. In Sweden, the "Lucy brides," topped with crowns of lighted candles, still walk the streets at dawn, delivering sweets to the neighbors.

This miraculous time of year was chosen by the Romans as their Saturnalia, the so-called liberties of December. The celebration featured a week of misrule, December 17 to 23, in which society was turned upside down. The very Roman idea of decorum was abandoned for the week, a time derived from the extra days the Roman calendar had to add each year to maintain its accuracy.

Those days meant freedom from the ordinary social laws that governed mankind. Slaves ruled freemen, children dictated to parents, and whatever went on under the mistletoe reigned. New Year's Eve, as we know it, had been invented. The week was also associated with game playing, lot drawing, and gambling. Most parties had a master of ceremonies, or arbiter bibendi, selected by lot to rule over the toasts, and a magister ludi, a games master. All of these would surface again in England, in Virginia, and in Williamsburg, especially on Twelfth Night.

In Virginia, Twelfth Night was the focus of the secular Christmas season. The most sumptuous balls, with many guests and lasting several days, were mounted at the finest homes. The college, the Indian school, and the grammar school, shut since December 16, only reopened after Twelfth Day. Plantation classrooms were suddenly unbarred as well.

Dancing, drinking, eating, and games ruled. Eating and games were combined into a new game, a lottery involving king and queen chess pieces hidden in a cake—or perhaps a bean and a pea, or two coins of different value, baked into the Twelfth Night cake. The lucky pieces settled the succession of the party and the cake from year to year. It was an ancient Christmas game.

And it reminds us of perhaps the most important medieval innovation in Christmas, the emphasis on families and the use of children to take part in or lead the celebrations. From among the children in each parish or each family, one would be selected by lot to lead the adults through the season.

Selecting this "King of the Bean," for instance, is a custom as old as the Roman Saturnalia. The idea was to bake a bean into a cake, with the honorific going to the person who drew the lucky portion. In England, the lord of the manor was charged with the solemn responsibility of providing the Twelfth Night cakes for his tenant families. This informal practice achieved the status of law at the village of North Curry, Somerset, in 1314.

It was also customary for the youngest in the household to slice and serve the cake. In sixteenth-century France, the child hid under the table and called out the name of the guest to be served as each piece was cut. The youth's innocence caused the game to be tamperproof, an idea that's apt at Christmas. First, because of the Christ child Himself. The second link is with the feast of Childermas, December 28, the service in remembrance of the Holy Innocents the Bible says were slain by Herod.

That's the thing about Twelfth Night: you never quite know whether it's serious or light, tragedy or comedy. Part of the day's solemnity is simply because it's the close of the Christmas joy. Shakespeare couldn't sort out whether it was supposed to be a happy or somber occasion, and so he called his play Twelfth Night, or What You Will.

Well before the age of the Christmas card, people wished each other well, an appropriate reflection of the love and charity expected at this sacred season.

Still, as we look at the documentary evidence for the ways Christmas was kept in Williamsburg, there's something decidedly subdued about it all. The General Assembly was sometimes adjourned early in deference to the season, but there's not much cheer in the air.

In 1764 and 1766, Governor Francis Fauquier closed the assembly in the middle of December "considering the Season of the Year." And Governor Norborne Berkeley, baron de Botetourt, in 1769 did the same: "As I understand that it is generally desired to adjourn over the Christmas Holidays," he wrote, "I do direct both houses to adjourn themselves." There's something perfunctory about it.

Most Virginians went to church on Christmas. Still, there were no Yule logs and no wassailing, revered medieval traditions in much of Britain. And no Christmas cards or Christmas trees either, which don't show up until the middle of the nineteenth century.

Nor was there much gift giving. Children may have been offered an improving book. Servants and slaves were sometimes given Christmas "boxes," a custom that would lead to Britain's "Boxing Day," December 26, the day on which the boxes were presented to the underlings with feudal pomp.

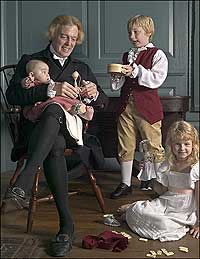

Interpreter Bill Barker as Thomas Jefferson dandles and delights grandchildren, from left, Jackson Perry, Weldon Perry, and Lydia Dean.

Traditionally, the boxes were terra-cotta earthenware with a slot in the top for inserting coins. On Boxing Day the vessels were broken, revealing their treasures—trifles, small change, or decorative pins and ribbons. Mainly, the boxes were easy metaphors: "It is a shame for a rich Christian to be like a christmas-box," wrote an English bishop in 1615, "that receives all, and nothing can be got out till it be broken in pieces."

On Christmas Day, 1773, a visiting tutor at Robert Carter's vast estate, Nomini Hall, in Westmoreland County, writes in his journal that he feels obliged to contribute to the "Christmas Box, as they call it." And so he gives money to the men and women who black his shoes, groom his horse, make his bed, kindle fires in his bedroom and schoolroom, and wait on him at table. His outlay for the season: three shillings, nine pence. But there is no box. He's handing the coins directly to them.

It's not until the nineteenth century that the mania for Christmas gifts takes off. But as early as 1809, Thomas Jefferson's grandson, age eight, is said to be "at this moment running about with his cousins bawling out 'a merry christmas' 'a christmas gift &c.'"

In time, gift giving and receiving take their place in the grand parade of Christmas customs that are still with us. And it happens fast, as new Christmas ideas are snapped up by a public made to feel inferior by the elegant and storied traditions they no longer understand. And so newer and easier things become instant traditions.

In 1642, Sir Thomas Browne wrote: "Thus is man that great and true amphibian whose nature is disposed to live, not only like other creatures in divers elements, but in divided and distinguished worlds ...the one visible, the other invisible." Browne saw that men, whether in America or in Britain, were in essence scaly beings with their great shiny tails mired in the muck of the material world while their torsos and heads poked up into the spiritual.

So it was with the English colonists in Virginia. There was certainly a spirit world all around, but there was also work to be done. The way they celebrated Christmas reflected this notion. It was improving and impious at once, sublime and ridiculous. As another writer very much associated with Christmas, Charles Dickens, once said, it was all very much "streaky bacon."

Michael Olmert teaches Shakespeare at the University of Maryland. His book on history, custom, and folklore is called Milton's Teeth and Ovid's Umbrella.

Read more articles from the Foundation's journal, “Colonial Williamsburg”.