Page content

Paint the Town

"The colors tell the story"

by Paul Aron

Conservation Material Analyst Kirstin Moffitt uses a high-powered fluorescence microscope in Colonial Williamsburg's Materials Analysis lab to study paint layers. And all she needs

is a tiny flake of paint.

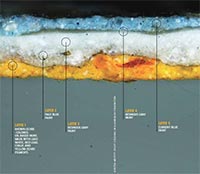

This sample is from the Seymour Powell Tenement Stair rail.

"Today we look at magnified samples in cross section and conduct extensive research with other equipment in Colonial Williamsburg's Materials Analysis lab," Webster said. "We can identify each layer of paint, pigments, binders, driers, primer layers, finish coats and a multiÂtude of other information that allows us to better understand and represent our structures." This sample is from the Seymour Powell Tenement Cornice.

The changes are as obvious as the exterior color of the Grissell Hay Lodging House, and as subtle as the white Benjamin Waller House becoming gray.

Returning guests have sometimes been startled to find buildings in Colonial Williamsburg's Historic Area painted in very different colors than they remember. For example, the Peyton Randolph House, once white, is now brownish red. The change was a result of technology that allowed researchers to analyze the layers of paint on the building and discover the original color of the house.

Interpreting what the colors said about the Colonists is by no means simple. The brownish-red color, for instance, could be very misleading because in the 18th century, it could be created cheaply with a red iron oxide pigment. The popularity of this color — which started to fall out of fashion after 1760 — would have been a strange choice for Peyton Randolph, the man who would lead every major assembly in which he sat, from the House of Burgesses to the Continental Congress.

But the reason that Randolph stuck with the color — a richer, more stable brownish red — likely had less to do with the fashion of the day and more to do with trying to trick onlookers. Randolph might have chosen the color to give the impression that the house, seen from a distance, was made of the higher-status brick; wooden details on the house certainly resemble details seen on brick structures.

"There were many factors that impacted color in the 18th century," said Matthew Webster, director of the Foundation's Grainger Department of Architectural Preservation. "What was the individual trying to achieve? What was stylish during the period? What material was available?

"What we can say is that color tells a story."

The color changes in the Historic Area were the result of significant advances in understanding the science of paint. When the restoration of Williamsburg began in the 1920s, researchers scratched through the painted surfaces to expose what they thought were the earliest layers of paint and then repainted with corresponding colors.

Yet, when these first researchers chose colors to match the earliest layers, they didn't take into account that paint colors change as they age. The breakdown of components such as the oil from which paint is made and the buildup of dirt over hundreds of years often darkened the paint. Paint that looked tan in 1929 originally might have been cream, for example. The muted tones many associate with Williamsburg were once very vibrant reds and yellows and blues that broke down over the years.

Take the Travis House, which early studies identified as having interior woodwork painted light green.

"Our current knowledge of 18th-century paint production tells us that linseed oil was used to make this paint, and we know as it ages, it yellows," Webster explained. "Modern analysis shows us that the pigment used was Prussian blue — a pigment that we know starts off as blue — when exposed to light turns to green and gray. Coupled with the yellowing associated with the aging oil, the color we see with the scratch test is much different than what was seen in the 18th century. The light green we see from the scratch testing was actually a vibrant baby blue in the 18th century."

Members of the conservation staff in the Colonial Williamsburg analytical lab now look at the paint samples through powerful microscopes, which sometimes reveal additional layers of paint.

"Today we look at magnified samples in cross section and conduct extensive research with other equipment in Colonial Williamsburg's conservation labs," Webster said. "We can identify each layer of paint, pigments, binders, driers, primer layers, finish coats and a multitude of other information that allows us to better understand and represent our structures."

Documentary evidence also comes into play. Advertisements in The Virginia Gazette mention pigments like Prussian blue, ochre, Spanish brown and dragon's-blood — clear hints about the Williamsburg palette. In a few cases, researchers have been very lucky. A 1798 contract between St. George Tucker and house painter Jeremiah Satterwhite lists the materials, colors and application techniques to be used to paint the Tucker house. That agreement reveals the exact paint scheme, including the red roof.

Other times, Colonial Williamsburg's collections have played key roles. The building now known as Charlton's Coffeehouse was dismantled around 1880, but more than 200 pieces of the original structure survived and eventually made their way into the Colonial Williamsburg architectural collection. These pieces allowed researchers to gather evidence of both the interior and exterior paints, and re-create the accurate interior and exterior finishes seen on the building today

Yet, despite all the evidence, choosing colors still requires some guesses — albeit educated ones. For the Bryan House, there were no original pieces to be studied. So researchers turned to the Robert Carter House, which had an intact paint history. Around 1780, the Robert Carter house was painted yellow, giving researchers a plausible color for the Bryan House.

Researchers also considered the status of the owners. Like the Bryan House, the James Moir and George Davenport houses have no surviving painted building materials. However, documents provided insights. The Moir house was new in the 1770s and was valued at the high price of 555 pounds and by 1780 was valued at 1,100 pounds. "This indicated a higher-status structure, causing us to choose the vibrant yellow ochre color," Webster said.

In contrast, the George Davenport house was more than 50 years old in the 1770s when the house and estate were valued at 70 pounds. Hence the cheaper and aesthetically dated brown color you see today.

"In reality, we should really pull off some siding and punch holes in the roof if we truly want to show the 1770s condition," Webster quipped.

He added, "The Moir and Davenport houses sit next door to each other and, just like in the 18th century, the colors tell the story."