Page content

Online Extras

Zoom in on Architectural Drawings from the Restoration

Perry Dean Rogers, Boston

Hopkinson’s portrait of Perry, Shaw, Shurcliff, and Hepburn, the four “designers of beauty” who gave Williamsburg a new birth when they undertook, for John D. Rockefeller Jr., the restoration of the former colonial Virginia capital in 1927. Shurcliff, a somewhat flamboyant landscape architect, shown standing in this composition, does not appear in the final rendition but was accorded a separate painting.

Colonial Williamsburg

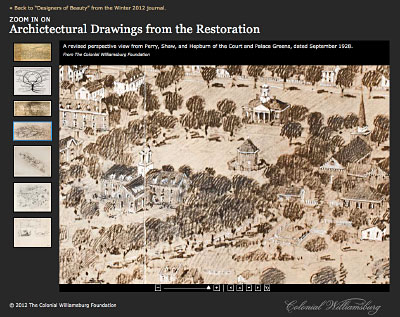

From the Boston firm of Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn, a sketch of the proposed restoration of the Court and Palace Green area of Williamburg, with Bruton Parish Church to the left and the Ludwell Paradise House to the far right on Duke of Gloucester Street.

Colonial Williamsburg

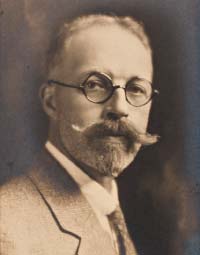

Arthur Asahel Shurcliff

The landscape and building architects brought different talents but a shared sensibility to the task of restoring the colonial capital.

Colonial Williamsburg

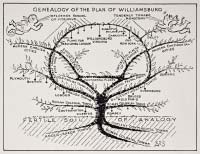

In a 1938 article in Landscape Architecture, Arthur Shurcliff drew a family tree to illustrate the design influences on Williamsburg’s Restoration.

Colonial Williamsburg

A 1927 sketch of the town from Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn, with the College of William and Mary, right, on the west side

Colonial Williamsburg

A revised perspective view from Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn of the Court and Palace Greens, dated September 1928

Designers of Beauty

Academic Training and Williamsburg’s Architectural Restoration

by George Humphrey Yetter

American portrait painter Charles Sydney Hopkinson inscribed his oil study of architects William Graves Perry, Thomas Mott Shaw, Andrew Hopewell Hepburn, and Arthur Asahel Shurcliff: “To my four friends, designers of beauty.” Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn, aided by Shurcliff, a landscape architect, planned the restoration of Williamsburg, a colonial Virginia capital, to feature baroque axial vistas, open spaces, and nodal location of public buildings. These aspects of Beaux-Arts architectural training—pervasive during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—were among the educational cornerstones of Colonial Williamsburg’s creators.

In 1924, Dr. William Archer Rutherfoord Goodwin, a professor and fund-raiser for the College of William and Mary, wrote to Edsel Ford, son of auto magnate Henry Ford, suggesting that his father buy and preserve the town.

It would be the most unique and spectacular gift to American history and to the preservation of American traditions that could be made by an American. Other men have bought rare books and preserved historic houses. No man yet has had the vision and courage to buy and to preserve a colonial village, and Williamsburg is the one remaining colonial village which any man could buy.

In the same letter, Goodwin, who in 1926 would become rector of the town’s Bruton Parish Church for the second time, alludes to the New York church architect J. Stewart Barney, who in 1906 supervised a restoration of Bruton to what was thought to be its original form.

In 1923, as planning began for a William and Mary campus expansion, Goodwin turned to Barney again, and attempted to enroll him as the consulting architect. After several visits, Barney declined, but during one of them, Goodwin later wrote, the New Yorker suggested restoring the city’s eighteenth-century homes for use as student and faculty housing. By 1924, Goodwin was turning the idea into a larger plan, and asked Barney to execute it. Barney, fifty-five, demurred because of his age, saying its completion would require “half a generation.”

Thomas Tallmadge, who had visited Williamsburg and suggested restoration of Palace Green, was unwilling, too, because of the demands of a forthcoming book. Charles Allerton Coolidge, of the firm of Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge—successors to H. H. Richardson—could not accept but suggested the young Boston partnership of Perry, Shaw & Hepburn.

Two years later, in 1926, Perry visited Williamsburg twice on his own and on the second trip met Goodwin, who was renovating the Wythe House to serve as Bruton’s parish house. The architect helped sketch a missing cornice and later provided authentic door hardware to replace missing examples. A year after, remembering Perry’s interest, the rector acted on Coolidge’s recommendation. Perry accepted with alacrity.

The choice was auspicious, and the approaching Great Depression was, probably, the one time in American history when even a Rockefeller could have acquired an entire town. The partners were individually and collectively ideal for the work. As Edward Chappell, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s Shirley H. and Richard D. Roberts director of architectural and archaeological research and archaeology, has written:

Varied personalities and talents resulted in the partners’ pursuing different parts of the firm’s work. Employees remember Perry as a successful promoter, Shaw as a rational space planner, and Hepburn as the talented designer.

Perry had been raised in a High Street mansion in Newburyport, Massachusetts, attended Harvard, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the École des Beaux-Arts. At MIT, he was a student of Constant Antoine Désiré Despradelle, known for his popularization of the classical Beaux Arts style. Guy Lowell, another of his students, said that “competitive camaraderie and the judging of projects led students to collaboration and an exchange of ideas.” The aspects of collaboration and thoughtful interchange were to be important facets in the Williamsburg project.

While at the École, Perry attended the atelier, or studio, of Victor Alexandre Fréderic Laloux, a great favorite of American architectural students. Laloux was adept at inculcation of the Beaux Arts educational system, involving complex structures requiring clear, readable plans. Among his other students was William Lawrence Bottomley, an architect familiar to Virginians for his early to mid-twentieth century renditions of elegant homes in the colonial style.

Perry developed an excellent rapport with John D. Rockefeller Jr., the philanthropist who agreed in 1927 to pay for the restoration after Ford demurred. As they walked down Duke of Gloucester Street in 1932, Rockefeller asked the architect what he thought of the reconstructed Raleigh Tavern.

“Mr. Rockefeller, I think it looks like a million dollars.”

“Thank you, Mr. Perry, you’re the only man in town who’s been frank enough to put a fair appraisal on that building.”

Familiar with the ornate Gilded Age mansions of H. H. Richardson and McKim, Mead & White because of his birth in Newport, Rhode Island, Shaw, second principal in the firm, also was influenced by the grand, classical architectural forms of the Great White City at Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exposition. He said, “It waked people up to the fact that there were enormous possibilities of beauty in the old classic forms.” Shaw traced the Williamsburg architectural style through the English Georgian period and the Italian Renaissance to the architecture of Greece and Rome.

Shaw graduated from Harvard and attended the École, too. He was a student in the atelier of Jean-Louis Pascal, another prominent academic French architect who influenced international students. Lessons of symmetry, balanced arrangement, and ordered elegance are readable in designs Hepburn produced for buildings in the evolving Williamsburg Restoration. Paul Cret, a French-American architect known for his streamlined variations on the classical mode, also studied with Pascal.

Shaw’s father, the artist Henry Russell Shaw, studied sculpture under Cyrus Durgin and painting under May Hallowell at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Shaw exhibited at the Salon during his years at the École and his father-in-law, painter Henry B. Quinan, was a pupil of painter Jean-Paul Laurens at the École Nationale Superieure des Beaux-Arts.

Reminiscing about the architects’ disciplined endeavor on the Williamsburg project, Shaw said: “I worked on those drawings. We all did. We all worked on them (just like a projet in the École des Beaux-Arts) to get them out.” Referring to their initial presentation drawings, he said they were looked at as a “pipe dream” without any comprehension of the scale into which they were to grow. A research staff was quickly assembled for advice on location, appearance, and historical references on the restored and reconstructed buildings. “Nothing was ever done without a good reason,” he said. “If there were no documented reasons for doing a particular thing, we didn’t do it.”

Hepburn, a Pennsylvanian and the third partner, attended architecture school at MIT, where he met the Virginian Robert E. Lee Taylor. Both were members of Harry Morse’s architectural office in Philadelphia following graduation. The 1907 Jamestown Tercentennial Exhibition brought a building boom for Norfolk, the principal celebration site, and Hepburn and Taylor formed a partnership there.

Hepburn remembered bringing down some early drawings depicting the Williamsburg Restoration to Goodwin and former William and Mary president and historian Lyon Gardiner Tyler. Tyler’s book Williamsburg: The Old Colonial Capital was a ready source of information. Hepburn said he thought that Tyler’s enthusiasm for Williamsburg’s history might have stimulated Goodwin’s interest.

Todd & Brown, early engineers on the project, at first questioned the need to build things exactly as they had been in the past. They later became convinced of the need for authenticity, however, so that the result, as Hepburn said, was

not what we wanted to do and not what we thought it ought to be, but what had been there if there was any possible way of finding out what it had been. We became regular Sherlock Holmeses. We had to be. We had to throw out things that were just pure guesswork if we could possibly find anything definite. People always say, “Well, wasn’t it fun?” Of course, it was interesting, but it wasn’t fun exactly. It was hard work.

The combined strengths of these three architects coalesced to assimilate voluminous research and produce drawings that persuaded Rockefeller and his lieutenants to undertake what became the largest preservation effort in America.

Goodwin canvassed opinions from America’s foremost architects of the era, including Charles A. Platt and Lawrence Kocher, a modernist in the International Style. Charles A. Coolidge, a student of the country’s first academically trained architect, H. H. Richardson, wrote in 1926 to Bishop Charles F. Slattery concerning Perry’s choice: “He was in my office for a number of years and I have no hesitation in saying that I do not think that Dr. Goodwin could get anybody better.”

Ralph Adams Cram, America’s preeminent ecclesiastical designer, wrote to Goodwin the next year and said:

It ought not to be necessary for me to say that I have the keenest interest in the work that is going forward at Williamsburg. Not only is this one of the most historical places in America, overhung by innumerable historic associations, but it is also, or should be, a Mecca for architectural pilgrimages. Mr. Perry has shown me all his plans. . . . It seems to me the architects are approaching this problem in exactly the right manner and their solution seems to me not only accurate archaeologically, but strikingly successful from an architectural point of view.

The final ingredient was landscape architect Shurcliff’s garden designs, framing the architectural whole. Shurcliff grew up on Boston’s Beacon Hill and was descended from Pilgrim stock. With degrees from MIT and Harvard, he began work in the office of Frederick Law Olmsted Sr., the father of landscape architecture in America. With Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., Shurcliff helped establish at Harvard America’s first degree program in landscape architecture.

He studied at the Boston Architectural Club under Professor Despradelle, the Beaux Arts trained architect with whom Perry studied. Shurcliff was a lecturer in town planning at Harvard and MIT, where he later remembered using Williamsburg town plans in classes.

His designs for the Emerald Necklace series of parks surrounding metropolitan Boston include axial vistas, circles, and ordered symmetry associated with the academic style.

Shurcliff was the nephew of the American landscape painter Roswell Morse Shurtleff, and his wife was a niece of the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The family spent summers at the popular artists’ colony of Cornish, New Hampshire, where the mutual influence of many artists, architects, and writers in residence was pervasive. Bucolic scenery, with views across the Connecticut River to Mount Ascutney in Vermont, was said to resemble Italian landscapes. The late nineteenth century came right after the American Renaissance, during which artists were rediscovering the past as a source of inspiration.

The garden historian Ann Leighton writes that the grand axial vistas, views aligned along a single axis, in classically inspired gardens of America’s Gilded Age evolved from Andre Le Nôtre, the eighteenth-century garden planner for Louis XIV’s Versailles. The technique of creating before and after scenes to show suggested garden alterations originated with the eighteenth-century English garden designer Humphry Repton and was another idea adopted by Shurcliff.

A prolific author, Shurcliff illustrates his wit and wisdom in romantic terms when he identifies the “skinner,” or remover of essential elements from a historic site. Describing the mature landscape, he writes: “When the full beauty began to reign indoors and in the garden, along came the ‘skinner.’ He runs ahead of old Father Time with a reaping hook more potent for instant ruin than the slowly swinging scythe.” He recognized the importance of amalgamating building and setting as indoor and outdoor rooms—each evolving and contributing to the full effect of the other. Perry later said he was a “poet with the utmost capacity, with an international reputation, competent, capable, indispensable.”

Before beginning installation of landscaping for Williamsburg’s Historic Area, Shurcliff compiled a large folio study of “Southern Places,” an intensive investigation of extant colonial gardens throughout the Virginia Tidewater. He included photographs and detailed measured garden plans.

Perry said:

Mr. Shurcliff is the type of man with whom it is an inspiration to work. He is clear, simple, direct, energetic and, personally, very charming. His work is of the highest order and he appeals to us particularly since he has a personality which is most adaptable to collaboration with others.

As had the other architects, he learned to thrive through interaction with peers so that from the fertile ground of the imagination a garden grew.

Goodwin said:

The landscape architect has by extensive investigation and rare imagination, recaptured the form and beauty of the colonial gardens and created vistas of loveliness to intrigue the thought and vision of visitors to recapture a vanished past. Soon, the Duke of Gloucester Street . . . will present a shaded “King’s Highway,” leading from “Queen Anne’s Capitol” building to “Their Majesties” ancient College of William and Mary.

Charles Hopkinson’s inscription on the Perry, Shaw, Hepburn, and Shurcliff joint portrait oil study has proven apt.

George Humphrey Yetter, associate curator of architectural drawings and research collections at Colonial Williamsburg’s John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, is the author of Williamsburg: Before and After, and contributed to the autumn 1992 journal the story “When Blackbeard Scourged the Seas.”