Page content

Wilkes, Liberty, and Number 45

by Jack Lynch

Member of Parliament, political agitator, friend of freedom, demagogue, wit, libertine, pornographer, and shameless self-promoter, England's John Wilkes was to colonial Americans an idol. Boston's Sons of Liberty, which counted among its number John Hancock and Samuel Adams, identified Wilkes with their cause; our forefathers named towns and babies for him; and his fights against government oppression helped inspire the Bill of Rights. Wilkes was at the center of many an important eighteenth-century political change, but to some—Benjamin Franklin, for instance—he seemed an unlikely hero.

For one thing, his personal immorality was legendary. He belonged to the Knights of St. Francis of Wycombe, better known as the Hellfire Club or the Monks of Medmenham Abbey. The members of this secret society dressed in Franciscan robes and parodied Roman Catholic rituals to engage in ribaldry and drunken orgies, often with prostitutes dressed as nuns. Wilkes in particular was noted for his wicked humor. When the Earl of Sandwich, a sometime friend, told him that "you will die either on the gallows, or of the pox," Wilkes said, "That must depend on whether I embrace your lordship's principles or your mistress."

Wilkes was ambitious for political power, and after a few failed attempts was elected to the House of Commons in 1757. His beginnings were unpromising. There is no sign he was then especially beloved by the public—like many representatives of small districts, he won election by bribing voters—and he said hardly a word in Parliament. Shortly after his arrival his hopes of promotion were dashed when the government of William Pitt the Elder, the first earl of Chatham, fell. Rather than despair, he learned to thrive as a member of the opposition. He spent much of his early career twitting John Stuart, the Earl of Bute, and learning how to use his talent for ridicule to gain international fame.

Bute had been tutor to the Prince of Wales, and became prime minister soon after the prince became King George III in 1760. Whatever Bute's qualifications as an administrator, he was a poor communicator; he therefore hired novelist and historian Tobias Smollett to edit a government-friendly newspaper, The Briton. Wilkes saw an opportunity. Just a week after the first issue appeared, he and friend Charles Churchill began anonymous publication of The North Briton, a title that alluded to the Scottish origins of Bute and Smollett.

Every issue of The North Briton was crowded with scandalous rumors and insults. Lord Egremont was "a weak, passionate, and insolent secretary of state," and Secretary of the Treasury Samuel Martin was "the most treacherous, base, selfish, mean, abject, low-lived and dirty fellow, that ever wriggled himself into a secretaryship." Bute, Wilkes's favorite target, was supposed to be Jacobite and involved in an affair with the king's mother. The North Briton No. 5 tells the story of Roger de Mortimer, the manipulative regent during Edward III's minority, who was the lover of the Queen Mother Isabella. No one could miss the parallels with Bute. Wilkes so enjoyed the story that he published an edition of an old play, The Fall of Mortimer, with a satirical dedication to his lordship: "History does not furnish a more striking contrast than there is between the two ministers in the reigns of Edward the Third and George the Third." He went on to offer ironic praise of Bute's talent as an actor, particularly in "the scene in Hamlet where you pour fatal poison into the ear of a good, unsuspecting King." Each week more abuse spewed forth. Despite, or perhaps because of, the recklessly down-and-dirty tone, The North Briton sold 2,000 copies a week—nearly ten times the circulation of The Briton. As Wilkes's biographer Charles Chevenix Trench notes, "Wilkes made Bute the most hated Minister the country had known."

It is hard to explain Wilkes's animus. He disliked "the late inglorious peace" Bute helped to negotiate after the Seven Years' War, but it seems he had committed only two unforgivable sins: interfering with Wilkes's personal advancement and being Scottish. Years later, Bute's daughter asked Wilkes why he hated her father. "Hate him?" he said. "No such thing. I had no dislike to him as a man, and I thought him a good Minister. But 'twas my game to abuse him." Whatever prompted Wilkes to torment him, Bute was forced to resign April 8, 1763.

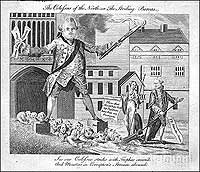

Lord North astride the Parliamentary sewage of bribery and corruption. In a 1774 London Magazine cartoon, Wilkes will "stem the stream" for Britannia with his broom.

After Bute's fall, Wilkes decided to let The North Briton lapse, and for a time no issues appeared. But polite silence was not for him. On April 13 he wondered in the press, "The SCOTTISH minister has indeed retired. Is HIS influence at an end?" When he saw a draft of the king's speech to Parliament, he wrote his most vicious essay yet. The North Briton No. 45 appeared April 23, 1763. To modern eyes, it doesn't appear especially incendiary—no more rough-and-tumble than most political pamphlets of the day. But Wilkes had crossed a line. It was a strict rule that the king was above reproach, and that only his ministers could be criticized. In No. 45 Wilkes began by playing this game, insisting, "The King's Speech has always been considered . . . as the Speech of the Minister." But with passages like this, Wilkes left little doubt that the king himself was the target:

A despotic minister will always endeavour to dazzle the prince with high flown ideas of the prerogative and honour of the crown. I wish as much any man in the kingdom to see the honour of the crown maintained in a manner truly becoming Royalty. I lament to see it sunk even to prostitution.

Such sentiments were in keeping with one of his antimonarchical witticisms. When asked to join in a game of cards, he said, "Dear lady, do not ask me. I am so ignorant that I cannot tell a King from a knave"—an astonishingly daring wisecrack in an era when the mildest criticism of the monarch could mean a charge of treason.

George III was furious, and ordered the arrest of the author of No. 45. The attorney general and the solicitor general were asked whether the paper warranted prosecution. April 27 they announced their opinion—it was seditious libel, designed to turn public opinion against the king—and drew up a warrant for his arrest. The prosecution, though, made procedural blunders that Wilkes used to his advantage. First, they issued a general warrant, which named "the authors, printers, and publishers, of a seditious and treasonable paper intitled 'the North Briton, number xlv,'" but gave no names. General warrants were of dubious legality, since they authorized the king's officers to seize anyone they suspected. Forty-nine people, most of them innocent, were arrested. More troublesome for the government, Wilkes claimed parliamentary privilege: as a member of the House of Commons, he was immune from arrest for anything short of treason or breach of the peace.

A series of trials began to consider the legal and procedural questions. Wilkes adored the limelight. Before a large crowd in the Court of Common Pleas, he said his case would "teach ministers of arbitrary principles, that the liberty of an English subject is not to be sported away with impunity, in this cruel and despotic manner." His trial, he said, would "determine at once whether English liberty be a reality or a shadow." Wilkes prevailed: the court ruled that he was exempt from prosecution and that the general warrant was invalid. The precedent is still cited in American courts.

Energized by Wilkes's victory, the others scooped up by the general warrant sued the government—an unprecedented action—and won, precipitating what scholar Arthur Cash calls "a momentous shift in the locus of power in government" from the privileged to the masses. Soon cries of "Wilkes and Liberty!" were heard across London, and the author of No. 45 embodied a movement of revolt against the government. The number 45 became a symbol of radical politics: one liberty-loving parson delivered a sermon on the forty-fifth verse of Psalm 119, "I will walk in Liberty, for I keep thy precepts."

Emboldened by his popularity, Wilkes reprinted No. 45 and began printing a pornographic poem he wrote with his friend Thomas Potter, An Essay on Woman. Twelve incomplete copies were struck, and those have been destroyed, but fragments survive. This parody of Alexander Pope's dignified Essay on Man, loaded with attacks on prominent politicians, is so obscene that hardly a couplet can be reprinted here. The government again decided to prosecute him, but the ministers had learned a lesson: since they could not proceed against a member of Parliament, they expelled him from the House of Commons before charging him with blasphemous libel. He fled the country, living in exile for four years on the donations of wealthy Whigs.

Wilkes returned in 1768, still an outlaw, but still politically ambitious and still a popular hero. Middlesex elected him to the House of Commons, after which he was arrested and imprisoned for his role in publishing The North Briton and the Essay on Woman. From prison he addressed his outraged supporters, who broke out in deadly riots. The catastrophe increased his popularity. The government, however, refused to surrender. Angered by the election of a convict and a seditious libertine, the Commons expelled him February 3, 1769. Middlesex reelected him February 16, even as he sat in prison; a day later the Commons declared the election void and expelled him again. Middlesex elected him again on March 16; he was expelled again the next day. After his fourth election, April 13, the Parliament changed its tactics. Although Wilkes had received 1,143 votes and his opponent, Colonel Henry Lawes Luttrell, 296, the House of Commons ruled that Luttrell "ought to have been returned," and declared him the winner. The government's victory was Pyrrhic, and succeeded only in making Wilkes more popular than ever. His supporters rallied to defend him, and the old cries of "Wilkes and Liberty!" once again echoed across the country.

Shortly before his twenty-two-month prison term ended, Wilkes was made a City of London alderman. In 1771 he became sheriff of London and Middlesex, and in 1774 Lord Mayor of London. Three weeks later he was elected once again to Parliament for Middlesex, and finally—on his fifth election to the seat—he was allowed to serve. He remained in the House of Commons sixteen years.

Wilkes's fame spread far beyond London: his bitterest wrangles with the government were in the 1760s and 1770s, just as British subjects in America were engaged in their own disputes with the king's government. Like Wilkes, the colonists resented the general warrants used against them, and they demanded the right to name their representatives. They saw in him a champion of the powerless against the privileged. As historian Pauline Maier has written, "In the years between 1768 and 1770 no English political figure evoked more enthusiasm in America than the radical John Wilkes."

Colonial newspapers buzzed with information about the persecuted friend of liberty. American support was not universal—Benjamin Franklin said Wilkes was "an outlaw . . . of bad personal character, not worth a farthing"—but in many liberty-loving circles he was a hero. Petitions and letters in his favor were signed by James Otis, John Adams, Samuel Adams, and John Hancock. Arthur Lee, a Virginian and a law student living in London, visited Wilkes in prison in 1768 and became an ardent supporter. Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, and Wilkesboro, North Carolina, took their names from the author of No. 45. Citizens of Virginia and Maryland resolved to send Wilkes forty-five hogsheads of tobacco, and forty-five women in Lexington, Massachusetts, joined to spin American linen to protest British policies. When news of Wilkes's release from prison reached Charleston, Club Forty-Five met at 7:45, drank forty-five toasts, and adjourned at 12:45. Sometimes the adulation was almost religious. Britannia's Intercession for the Deliverance of John Wilkes, Esq., from Persecution and Banishment included an imitation of the Apostle's Creed:

I believe in Wilkes, the firm patriot, maker of number 45. Who was born for our good. Suffered under arbitrary power. Was banished and imprisoned. He descended into purgatory, and returned some time after. He ascended here with honour and sitteth amidst the great assembly of the people, where he shall judge both the favourite and his creatures. I believe in the spirit of his abilities, that they will prove to the good of our country. In the resurrection of liberty, and the life of universal freedom forever. Amen.

Late in life his radical reputation began to fade: perhaps inevitably, the young firebrand became something of an establishment figure. When a woman cried "Wilkes and Liberty!" to the elder statesman, he said, "That's all over long ago." And by the 1780s, Americans had their own national concerns; all things British—even British radicals—declined in importance. Some have suggested that his principles were never sincere, that he was a corrupt and snobbish attention grabber who bought his way into Parliament and cynically manipulated the public for his own ends.

On a punch bowl in the Colonial Williamsburg collections, Wilkes's image and the cap of liberty encouraged colonists.

View detail View detailWhatever his motivation, he seems to have been a genuine convert to populist democracy. His record in Parliament is among the most progressive of his age. He introduced a bill to bring about "just and equal representation of the people of England in parliament," doing away with the rotten boroughs and the limitation of the franchise to property owners—a reform that had to wait more than half a century. He defended religious liberty, prisoners' rights, and freedom of the press. Mindful of his supporters across the Atlantic, he denounced the Declaratory and Townshend Acts and never stopped criticizing the war on America as "unjust, felonious and murderous." His arguments rarely carried the day in Parliament, but his failures may have been as important for America as his successes. Historians have argued that Wilkes's thwarted attempt to represent Middlesex was a turning point in American dealings with Britain. The government's behavior persuaded the colonists that the system was damaged beyond repair, that liberty meant nothing to the king, and that a solution would be found only in their own nation.

His legacy was important and lasting. He showed by example that the traditional relationship between governors and the governed could be more equitable. He taught people on both sides of the Atlantic about their rights, and showed them how to use the courts and public opinion to redress grievances. His electoral battles influenced the framers of the United States Constitution, who wrote articles explicitly spelling out the qualifications for election to offices. Whether he remained committed to the cause, whether his rhetoric was ever entirely heartfelt, his eloquent defense of the people's right to direct their own affairs rang true for a new radical generation.

Jack Lynch, author of The Age of Elizabeth in the Age of Johnson (Cambridge University Press, 2003), is assistant professor of English at Rutgers University in Newark, New Jersey. He contributed to the spring 2003 journal a story on St. George Tucker's adaptation of Blackstone's Commentaries.