Page content

"In Mind and Heart" with the Enslaved of Yesteryear

An Essay by Will Molineux

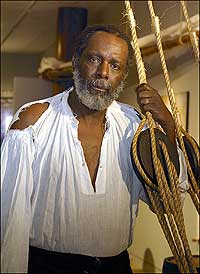

Wali Brandon retells the story of the Middle Passage at the Mariners' Museum in Newport News, Virginia.

In the dark, I almost stepped on his fingers. He was sitting on the floor with his hands to his sides as if to brace himself aboard a rolling ship. He was portraying a captive held below deck on his way to the Americas; he was depicting one of the millions of unregarded slaves from Western Africa. He was barefoot and wearing ragged breeches and a dirty, torn shirt. He was silent, until a mother and her smartly dressed youngster came by.

"Son," he called out, "come here and sit by me." His invitation was warm and unthreatening and readily accepted by the lad. "I want you to realize—I want you to know—your history and to be proud of your history."

The slave put his arm around the boy's shoulders. "You see, you are a descendant of some of the greatest people who ever walked the earth. Africa was a continent where tradesmen and jewelers and artists lived and worked long before—long before—the Europeans came upon them. You are one of their descendants."

He spoke slowly with confidence and authority. "Yes, yes, you are a descendant of slaves, but no one asked to be a slave. They fought against slavery. Ones that were of weak mind or body, they died. You are a descendant of some of the strongest people who ever walked this earth. They endured 400 years of slavery—400 years—and still they became a viable and a strong and a determined people. Don't let anyone take that away from you."

Then the young man got up and stood erect and quietly rejoined his mother, who turned and whispered to the slave, "Thank you."

It was a moving moment; it was a history lesson the young visitor to the Mariners' Museum in Newport News is likely to remember.

The man who portrayed the nameless slave is Wali Brandon, an interpreter of African American historical characters. He studied acting and history at Virginia Commonwealth University and believes passionately that Americans today—and young Americans in particular—should understand the lives of the people who preceded them.

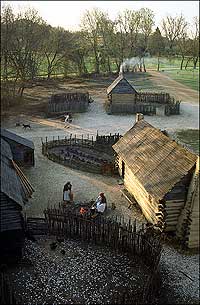

World within a world—the Slave Quarter at Carter's Grove, a few miles from Colonial Williamsburg's Historic Area. Photo by Dave Doody

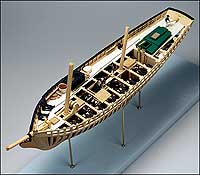

At Yorktown Victory Center, a model based on archaeological work at the Utopia slave quarter, near Williamsburg. Photo courtesy of Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation.

"You can read about people and what they did—and we should—but one needs to know how people felt and what people believed and what sustained them," Brandon said. He spoke with the fervor of a preacher. "Not just the leaders and the famous," he said, "but the ordinary as well. The record of their lives may be fragmentary at best, but their contributions shouldn't be taken for granted nor neglected." In other words, Brandon was saying that people must go beyond an intellectual appreciation of slavery to an emotional understanding.

And, he and I agree, it should always be kept in mind that slavery was, at all times, demeaning to slave and slave owner, whether they be the Spanish in the West Indies or the Portuguese in Brazil or the English in Virginia.

We were sitting together on a bench in the midst of the museum's special exhibition Captive Passage, the story of the transatlantic slave trade as told from a maritime perspective. Between the early sixteenth century and the second half of the nineteenth century an estimated ten and a half million Africans experienced the inhumanity of the Middle Passage—so called because it was the middle leg of the triangular trade route: Europe to Africa, Africa to the Americas, and the Americas back to Europe. The exhibit, to be moved this year to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, conveys the brutality of slavery and, as Brandon said, makes clear the points that slavery was, initially at least, caused by economic pressures and not racial hatred and that enslaved persons, by their heritage, labor, and skills, contributed significantly to the colonization and the development of the Western Hemisphere. After all, there were, during the first centuries of settlement, more Africans and African Americans than European immigrants in the New World.

Slavery was slow to start in Virginia. The first Africans—"twenty and odd," according to John Rolfe—were brought to Jamestown in 1619 by Dutch pirate-traders who had taken them at sea from Portuguese slavers. During the next thirty years a few hundred more slaves were brought into the colony from islands in the Caribbean Sea. Only as the seventeenth century ended were boatloads of slaves imported routinely from Africa to work in the tobacco fields around the Chesapeake Bay.

Today, we know little of them individually—not their names, not their personalities, their relationships, their places of burial. Certainly, their common plight of being separated from family and homeland and of being confined and mistreated—of being made property—haunted them and scarred their psyches. We can only try to imagine their emotional travail and despair, the pain of their shackles, and the depth of their fortitude.

But more is now known about their collective lives, thanks to remarkable research conducted during the past couple of decades—of documents and of sites where slaves lived. Two principal places where archaeologists have been working are not far from Colonial Williamsburg's Historic Area—places with such incongruous names as Rich Neck and Utopia. The slave population of colonial Virginia—the "other half"—is no longer out of mind.

Interpreters Rose McAphee, left, Danielle James, and Dakari Watson in a slave quarter log cabin

Click image to enlarge

The immensity of the slave trade has been made shockingly clear by the maritime records of more than 27,000 voyages compiled by the W. E. B. Du Bois Institute for Afro-American Research. These records, which account for perhaps 70 percent of the Atlantic slave trade between 1660 and 1867, tell of ship ownership, tonnage, and, more important, give the age, sex, mortality, and region of embarkation of many Africans. This database of Diaspora, which Harvard historian Bernard Bailyn likens to "a Hubble telescope to the past," was the subject of a 1998 international conference at the Bruton Heights School Education Center and was sponsored, in part, by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Scholars, such as Philip D. Morgan of the College of William and Mary, are rereading plantation and court documents and focusing on references to enslaved persons. His award-winning study of eighteenth-century black culture in the Chesapeake and the low country of South Carolina, Slave Counterpoint, gives new insight on the melding of Africans of various ethnic and cultural groups and their adaptation to English influences and rule.

It is archaeology," said Thomas E. Davidson, senior curator of the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation, "that is unveiling the last aspect of Virginia's colonial social history—the slave quarter." There were thousands of these collections of rude structures, yet not one of them survives intact today.

Physical evidence of their existence does, however, and that has attracted the interest of archaeologists at sites like Rich Neck, in what is now the upscale Holly Hills subdivision of Williamsburg, and Utopia on the James River at the edge of the gated Kingsmill community. And on the basis of what archaeologists are finding, Davidson has a pretty good idea of the dimensions of the one-room, dirt-floor living spaces. Consequently, he has more of an understanding of how enslaved persons lived when they were not at work and were relatively safe from the domination of the overseer.

Davidson is standing in front of a model of a slave quarter that is representative of one of those that stood not far from cultivated fields throughout Tidewater Virginia at the beginning of the eighteenth century. It is a model of an earthfast structure built on a framework of sturdy limbs of black locust, cedar, or cypress that were stuck into the ground. These slab-sided huts were intended to house what plantation masters considered to be economic units of production rather than human individuals and, therefore, were not intended to be permanent.

Davidson said that when the support posts decayed, they left stains easily detected. By measuring the intervals between posthole stains, and by identifying the location of the fireplace, it is a simple matter to plot the layout of the dwelling, which was typically fifteen by twenty feet. The chimneys were fashioned of sticks and mud. Sometimes there were two nonconnecting rooms—a sort of duplex arrangement. The huts, especially in early colonial times, were barracks where slaves were separated by sex. It is uncertain how many persons may have slept in them. By the mid-eighteenth century, however, slave quarters were mostly log cabin structures and occupied by persons related by kinship.

Cutaway model of a slave ship from the nineteenth century, its human cargo crowded below deck. Photo courtesy of Mariner's Museum.

"The slave quarters were arranged around an open courtyard where people would come together at sundown after a day of labor and on Sundays—a kind of community space," Davidson said. Such an arrangement for outdoor living in warm and humid climates is common in Africa and the Caribbean. "There was an open fire in the courtyard for communal cooking, and nearby there often was a small garden or penned livestock that were tended for their personal use," depending on the indulgence of the plantation owner.

"The slave quarter was a place where enslaved persons, who had no control over their own lives, could—even in the harshest of circumstances—assert a measure of control, of having personal time," Davidson said. It was also the place where children were nurtured and where bonds of friendship and family were established, tested, and sustained. And it was also a place where persons in bondage could conspire to subvert authority.

"It was a place where the African American culture evolved," Davidson said, handing me a folder that explains the meaning of the model. Davidson's text accompanies a drawing of a slave quarter and offers a logical conclusion: The slave quarter "was the center of a very complex set of cultural interactions and mediations. . . . Ultimately the quarter, a structure created by planters to control slaves, became something quite different, the wellspring of a new African-American way of life."

Although slave quarters had few, if any, furnishings, they had a feature that could be considered "closets"—personal storage space dug in the floor. They were shallow root cellars, to use a better term, where meat and vegetables were kept packed in pine needles or straw and where contraband items were hidden. Archaeologists have been surprised by what they have found.

Laboratory analysis of micro faunal and botanical remains indicates how enslaved persons supplemented the rations of Indian corn and pork allotted by the master. The science of zooarchaeology suggests they trapped birds and squirrels, foraged for berries and nuts, and, if streams were near, they fished.

Chickens were especially important, said Ywone Edwards-Ingram, who is in charge of Colonial Williamsburg's African American archaeological program. Chickens were, of course, valued for their eggs and meat, but their feathers and bones were used in African rituals. Edwards-Ingram is quick to remind me that enslaved persons brought with them from Africa agricultural and hunting skills. And, she said, their own cuisine. Excavations of root cellars, within and outside slave quarters, have yielded pieces of creamware, glassware, and delftware—and an occasional wine bottle. Even weapons and parts of firearms. Some items—coins and spoons—were found etched with African markings that had been treasured as protective charms.

When they were excavating the Utopia slave quarter, archaeologists uncovered the remains of twenty-five people, twelve of them children. Their bodies had been wrapped in cloth shrouds and placed in wooden coffins that faced east, toward the rising sun. One of the children was buried wearing a necklace of glass beads. Three men were buried with clay tobacco pipes, a custom of the Ibo people of West Africa. The remains were reinterred in a common grave and marked with a bronze plaque—perhaps the only such monument in Virginia.

"Every time I pass by—and I come here two or three times a year—I think of these people who worked here and lived here," said archaeologist Garrett Felser, "and the spirit of them falls on me." Felser, who is with the James River Institute of Archaeology, is one of several speakers on a chilly, windy Saturday in December at a memorial celebration of all those who, for a century after 1670, spent their lives at Utopia.

A Bible verse is read, and the Reverend Jacqueline Brown reminds us that those who died at Utopia "are now free with the Lord, just as they were free when they were in Africa—freedom to freedom." Willie Parker, president of the Friends of African-American History and a master printer in the Historic Area, said that those of us present can be, "in mind and heart," with the enslaved of yesteryear.

Then a chorus of community-minded men forms a circle under the bare oak trees and sings spirituals. Their sonorous voices are strong—"no more auction block for me." Then there is silence.

It is another moving moment—a lesson in remembrance of enslaved persons without identity whose lives had, until now, not been as clearly seen.

| |

African-American Interpretation at Colonial Williamsburg |

Virginia journalist Will Molineux contributed to the winter 2002-2003 journal an essay on William Wirt, the first biographer of Patrick Henry.