Page content

Dave Doody

Chief Kevin Brown stands beside the river that has borne his tribe’s name since before the English reached Jamestown, and is the eastern boundary of his reservation.

Colonial Williamsburg

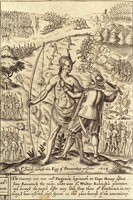

Pamunkey princess Pocahontas, “baptized in the Christian faith” as Rebecca, married John Rolfe.

Colonial Williamsburg

John Smith threatens Opechancanough, the “King of the Pamaunkee,” with a pistol in 1609.

Dave Doody

At the governor’s mansion in Richmond, Chief Brown, in headdress, brings the annual offering of venison and fowl to Governor Bob McDonnell, a promise kept for 350 years from a treaty dating to 1677.

Dave Doody

In the reservation’s museum, two Colonial Williamsburg gifts honor the tribe’s legacy. A replica silversmith’s shop medal and a coat sewn by journeyman tailor Mark Hutter commemorate a 1677 treaty.

Dave Doody

Chief Brown, examining a 1729 Carolina map, said, “We are part of American history . . . and proud of it.”

We Are Not Going To Go Away

Virginia’s Pamunkey Indians Greeted the Jamestown Settlers, but They Are Still Waiting for National Recognition

by Andrew G. Gardner

Beyond Virginia’s borders, the Pamunkey Indians are remembered, when they are remembered at all, mostly for a princess named Pocahontas. England’s Queen Elizabeth II probably knows more about the tribe than the average American: in 2007 she met a Pamunkey delegation during celebrations of Jamestown’s 400th anniversary.

When the 1607 colonists landed, the Pamunkey— 1,000 warriors strong—were the most powerful of the thirty-two tribes in the Powhatan paramount chiefdom, the loose association of Native Americans that dominated the Chesapeake region. Hunter gatherers, they looked to the woodlands for meat, clothing, and the stuff of shelter, fished the rivers, and grew such crops as maize, beans, and squash. Fifteen to twenty thousand people, the Powhatan commanded more than six thousand square miles, a territory that ranged leagues inland from the bay, all its tribes tributary to the Pamunkey chief Wahunsonacock, Pocahontas’s father. Now the Pamunkey domain amounts to a 1,200-acre King William County reservation twenty-five miles east of Richmond. There, thirty-four families—fewer than eighty people—make livings from renting out land for farming and duck hunting. About 120 more Pamunkey are scattered across the country.

Nevertheless, they are “a people who refused to vanish,” as historian Helen Rountree says. One of eight tribes Virginia recognizes, only they and their neighbors the Mattaponi established reservations, each secured by seventeenth-century treaties with Charles I and Charles II. In a 1677 compact, the Pamunkey agreed to pay to the governor a rent of “twentie beaver skinns” each autumn, a fee later amended to “Fin, Fur, or Feather.” They say that in 350 years they have not missed a payment of fish, wild turkey, or venison, these days ceremoniously delivered to the steps of the governor’s mansion in Richmond.

All the tribes that call Virginia home attempt to keep their cultures and their heritages alive, a struggle that spans centuries.

With the founding of the Jamestown colony came a clash of cultures. The Indians saw land as a common resource, like air or water. The English saw Virginia’s as underoccupied, and ripe for private ownership hedged with property rights. Wars began forthwith.

In 1622, the Pamunkey leader Opechancanough led what the colonists called a massacre and historians redefined as an uprising. The warriors of the Powhatan chiefdom saw it as a fight for what was theirs. Scattered in settlements along the James River, more than 350 English, perhaps a quarter of the colony, were “basely and barbarously murthered,” the Indians “not sparing eyther age or sexe, man, woman or childe.”

Virginia’s governor, Sir Francis Wyatt, decreed revenge. “Our firste worke,” he wrote, “is the expulsion of the Salvages to gaine free range of the countrey.” For nigh on twenty years, guerrilla war raged, the English raiding Pamunkey and other Powhatan villages. Indians fled into the forests, regrouped, and terrorized English outposts. But by the mid-1600s, the colonists near 8,000 strong, the struggle tipped in favor of the English.

In 1644, Opechancanough led a second colony-wide attack that killed between 300 and 500 colonists—far fewer proportionately than twenty-two years before, and not nearly so staggering a blow. Governor Sir William Berkeley led sixty soldiers into Pamunkey country to impose peace terms. A battle ensued. The Indians carried Opechancanough, nearing 100 and almost blind, to the battlefield on a stretcher. They held his eyelids held open so that “he might see the English die.” Berkeley’s troops routed the Pamunkey, and took Opechancanough to Jamestown, where a guard shot the prisoner in the back.

A treaty followed in 1646, the English dictating its terms to the new chief, Necotowance, requiring him to acknowledge that his tribe held its lands as vassals of Charles I. The English designated a reservation for Necotowance’s people at “Pamunkey Neck,” a thumb of land in the bend of the river that bears the tribal name. Tribal members could not cross its boundaries without permission.

More European immigrants set sail for Virginia, and Pamunkey property came under increasing pressure. The English earmarked treaty lands for colonial expansion. Pamunkey were forced to become servants, or enslaved.

An English census in 1669, aiming to determine how many Powhatan bowmen could be mustered to control the wolf population, found the population had fallen from 20,000 to less than 3,000. Disease and warfare had taken their tolls. Warriors numbered 725, with Pamunkey strength reduced to fifty bowmen and their families.

In 1676 a disaffected group of English planters led by renegade Nathaniel Bacon, a twenty-nine-year- old newcomer, attempted a coup against Berkeley. Among their prime targets were the Pamunkey tribe and its new leader Cockacoeske, Queen of the Pamunkey.

Bacon’s Rebellion collapsed with his death, apparently from typhoid—“the lousy disease”—but not before Charles II sent three commissioners from London to Jamestown to investigate and take depositions. One settler testified that the Indians were victims of grievous crimes perpetrated by planters who tricked them out of their lands and complained when the natives returned to settle the score. The upshot of the inquiry was 1677’s Articles of Peace, also known as the Treaty of Middle Plantation— as Williamsburg was in those days known.

Signing for the Pamunkey were Cockacoeske and her son, Captain John West, reputed to be the child of Colonel John West. The colonel farmed what had been Pamunkey reservation land and gave his name to West’s Point, today’s West Point, at the confluence of the Pamunkey and Mattaponi. The articles recapitulated much of the 1646 treaty, reaffirming that the Indians were English subjects paying annual tribute. Some ancestral lands were to be restored, and some basic human rights guaranteed— most trampled once the meddlesome commissioners went back to England.

Thinking to cement goodwill with the Pamunkey, the English made an agent of their new vassal Cockacoeske, an instrument in their dealings with other Powhatan tribes. She was to be crowned paramount chief in a coronation complete with cornet and purple robes. The finery was lost in a shipwreck, but an engraved silver frontlet, or badge, arrived, inscribed with Charles II’s crest and the words “Queene of Pamunkey.” The original is in the possession of Preservation Virginia. The tribe owns a duplicate created by Colonial Williamsburg’s silversmiths. It has pride of place in the Treaty Room of the Pamunkey Reservation Museum.

For the two centuries more, conflicts the Pamunkey wanted no part of brought troubles home to them. The French and Indian War may have been fought at the western frontier, but reports of Indian atrocities reinforced the mistrust and prejudice of English settlers toward their Tidewater Indian neighbors. The outcome of the Revolutionary War—its final major battle took place on the York River across from their ancestral abodes—gave them no more freedoms. The Indians were still seen as obstacles to settlement of undeveloped land.

Four score and seven years later, the Civil War put the Pamunkey and their reservation at the center of more hostilities not of their making. In 1862, the 100,000 Union troops in Major General George B. McClellan’s Peninsular Campaign arrived and billeted in and around Pamunkey property. Tribesmen served the northerners as guides, riverboat pilots, cooks, spies, and scouts. It ended with Confederate reprisals on the Pamunkey for having supported the repulsed Union forces. Moreover, the Pamunkey’s white neighbors still eyed their land, and pushed to have tribal treaty rights annulled. By the end of the nineteenth century, few more than 100 Pamunkey still lived on their treaty lands.

The next century would bring them a new challenge— one that would have profound repercussions— repercussions felt today.

Walter Ashby Plecker was a medical doctor by training. Born ten days before the Civil War began—his father fought for the Confederacy—Plecker became Virginia’s first state public health officer, eventually administering its new Vital Statistics Office for more than thirty years. Plecker, a white supremacist, was an enthusiast for the popular late nineteenth-century pseudoscience eugenics. Eugenicists believed in the racial inferiority of all non-Caucasians, and promoted strict segregation to forestall the procreation of whites with African Americans and others.

In 1924, Virginia adopted the Racial Integrity Act, a statute that decreed but two possible racial classifications: white or “colored.” Plecker, who lobbied for the measure, wrote in 1925 of “the considerable number of degenerate white women giving rise to mulatto children.” Keeper of the state’s births, deaths, and marriages records, he used his office to advance his beliefs and the state’s stringent racial codes, enactments that outlawed black and white marriages. Plecker embraced an extralegal “one drop rule,” which held that anyone with so much as a drop of “black blood” in his or her veins should be classified black—which he did.

Virginia’s Indians were not the primary targets of the racial restrictions—they were classified with whites—but they, Pamunkey included, became the law’s and Plecker’s victims anyway. In Plecker’s mind there was no longer such thing as a “pureblood” Virginia Indian. To him, all were descended of unions with free blacks. Suspecting that blacks were trying to pass as Indians to gain white status, particularly in the Chickahominy tribe, he ordered the state’s records of Indians revised to classify them all as “colored.” The legislature, however, adopted a “Pocahontas exception.” Realizing that prominent Virginians claiming Indian descent, including from the Pamunkey princess, would be now be classified as “colored,” the lawmakers excused individuals of one-sixteenth or less Native American ancestry.

“In Plecker’s mind we simply just did not exist,” Chief Kevin Brown says. “It was paper genocide pure and simple. Administratively, he was wiping us off the map.”

In 1969 the Supreme Court of the United States threw out the Racial Integrity Act. But for the Pamunkey and the other Virginia tribes, Plecker’s obsession still has a sting in its tail.

Neither the Pamunkey—who often describe themselves as a nation—nor Virginia’s other state approved tribes are recognized by the federal government. Since declaring independence, the United States has by treaty recognized 562 tribes, but the process of federal recognition is now much more demanding. Indian records altered during the Plecker era have made it hard to fill the genealogical gaps when trying to draw family trees—important to any federal claim for tribal sovereignty.

The Pamunkey Nation is determined. Chief Brown says, “We were overlooked in 1776 . . . that’s when we should have been recognized. We deserve justice. Our treaty was with England and predates the Constitution. Now it’s time to have the United States government recognize us for who we are. We are not going to go away.”

Federal recognition brings such benefits as sovereignty, government grants for health care and education, economic development, and housing finance. Billions of dollars are paid annually to federally recognized tribes. The Pamunkey see no reason why they or their tribal neighbors should not be eligible, too. “We’ve been here a long time,” Brown says. “Our reservation is from 1646. We have been part of Virginia’s Tidewater landscape for at least 10,000 years. We have the longest history of contact. It’s time.”

Elsewhere, tribal sovereignty opened reservation gates to gaming and casinos, fostering a potential for increased crime, corruption, and erosion of traditional ways of life. In most cases, Virginia’s tribal councils have emphatically rejected following that path. Nevertheless, some lawmakers and non-Indians are skeptical of the tribes’ assurances, and have consistently frustrated proposals for tribal sovereignty in Virginia.

The Pamunkey have asked the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs for recognition, and Brown is confident that in time it will come. “We’ve addressed the seven criteria they’re looking for—our heritage as a historic tribe, a continuity of culture, a continuation of government-to-government relationships, and so on. We’ve done all of that. We still pay that tribute— Fin, Fur or Feather—every year since way back.

“We’ve been working on this for twenty years,” he says. “We’ve spent over two and a half million dollars on it. There’s a lengthy, scholarly report that traces the genealogy of each family that’s on the tribal roll back as far as we can . . . sometimes to the 1700s.

“We know we’ll get federal recognition. It’s not a matter of if. It’s just a matter of when. They know who we are; they know how long we’ve been here. They can’t just turn their backs and ignore us. Whether they like it or not, we are part of American history . . . and proud of it.”

Andrew Gardner, who writes on Canada’s Salt Spring Island, contributed to the winter 2013 journal the article “How Did George Washington Make His Millions?”

Suggestions for further reading:

- James Horn, A Land as God Made It (New York, 2005).

- Daniel K Richter, Facing East from Indian Country (Cambridge, MA, 2001).

- Helen C. Rountree, Pocahontas’s People (Norman, OK,1990).