State, Dignity, Authority

Four Williamsburg Chairs Are Distinctive Expressions of Colonial Sophistication and Culture

by Graham Hood

Charles Red, portraying Speaker Peyton Randolph, tries out the reproduction Speaker's chair in the reconstructed House of Burgesses. - Photo by Dave Doody

The Speaker's chair traveled from Williamsburg to Virginia's new capital, Richmond, in 1780, but returned in 1930. - Photo by Hans Lorenz

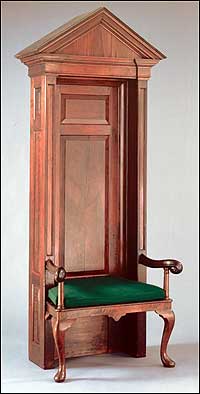

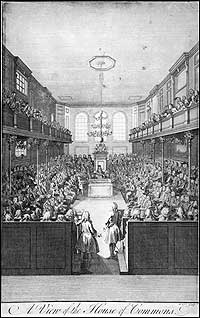

Williamsburg's Speaker's chair was much in the style of one in the British House of Commons. - Photo by Hans Lorenz

We most readily link the word "chair" with a piece of seating furniture, often but not always of wood, with four legs and a back, sometimes two arms—something more or less pleasingly designed to take the weight off one's feet. Few would quickly say, "Ah, yes, a seat of authority, state, or dignity; a throne, bench, judgment-seat." Yet that is one of the word's principal meanings. Another familiar word is "chairman," but the ceremony implicit in the term, and the emblem of that officeholder's authority, do not spring to mind.

In the more ceremonial societies of the colonial era, the insignia of leadership were many and varied, and they seemed valid and necessary whether the leaders were elected officials, lofty appointees, or of royal blood. Rich and specialized clothing bespoke eminence, as did costly furnishing textiles, jewels, and medallions, as well as thrones in a range of hierarchies.

Since Williamsburg was a very small colonial capital, it is a matter of surprise that four of these thrones, made and used in the eighteenth-century city, survive. It is a distinctive colonial expression. These thrones, or chairs, are of commanding presence, ambitious in form and complex in detail. They speak eloquently of the sophistication of colonial culture.

The earliest of the four was crafted for the House of Burgesses, the lower house of the Virginia legislature. To cite a 1703 specification, it was to be "a large Armed Chair for the Speaker to sit in, and a cushion stuft with hair Suitable to it." Within this influential assembly, it was the speaker's responsibility and privilege to be eminent, to be elevated above the fray, and to direct proceedings. The large armchair that gave symbolic form to that function, and that we admire today, was fashioned in the 1730s, and it is significant that it is a Williamsburg product rather than a London import. It survived the destruction of the Capitol by fire in 1747, it was a central point of the epochal debates of the 1760s and early 1770s in the House, it survived the Revolutionary War and the removal of the capital to Richmond in 1780, it emerged unscathed from the devastation of that city in the Civil War, and it returned to the Capitol when that building rose, phoenix-like, from its original foundations in 1930. It is a distinguished object with an extraordinary record.

Eighteenth-century commentators make clear that the Speaker's chair was designed to stand in the middle of the House toward the upper end, to be raised on at least two steps, and to be embellished with the symbol from which its authority derived, the royal coat of arms. It was Williamsburg's Edmund Randolph—nephew of Peyton, the most famous occupant of this seat in the colonial period—who said that the chair had a frontispiece or pediment "commemorative of the relation between the mother country and the colony." In other words, the royal arms were placed within or on the apex of the tall back.

A British scholar, Hugh Jones, who visited Williamsburg early in the eighteenth century, observed the parallels between the chambers and functions of the Capitol and those of the Houses of Lords and Commons in London. It is not surprising to find that the eighteenth-century speaker's chair in the House of Commons was topped by the royal arms boldly carved in the round, and it obviously served as a prototype for the Virginia chair.

Because of its style and material, it appears the Virginia chair was made in Williamsburg, a generation after the order of 1703. It is not that the formal, pedimented back is characteristic of a period or region but rather that the arms and legs are, and the material of which it is made. The boldly curved arms and their columnar supports might be as early as 1720, but the pronounced cabriole legs couldn't be earlier than the 1730s. All the visible wood is Virginia black walnut, with tulip poplar for the interior frame. Despite these indicators, it took former furniture curator Wallace Gusler to show, twenty-five years ago, that such features could also be seen in a related group of furniture that had strong historical and material links with Tidewater.

Saved from the conflagration of 1747 and still bearing signs of the fierce heat of that event, the Speaker's chair served its time-honored function in the newly remodeled House. It is the only thing we still have that was present at those historic debates, which counted for so much in our nation's history.

Since chairs have arms, legs, knees, ankles, feet, toes, and seats, one wonders if they might not also have ears? How much we would give to hear what this particular chair heard. In any event, it is less ironic than it is illuminating that one of the most fundamental symbols of the "rights of Englishmen"—formulated during centuries of strife and bloodshed, and enshrined in what many prominent Virginians proudly cited in the early 1770s as the pure British Constitution—was such a central feature of the prelude to Revolution.

Resurfacing in 1928, when the Rev. Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin purchased it for the Colonial Williamsburg, the governor's chair dates to about 1750. Its long legs dictated a footstool for the sitter. - Photo by Hans Lorenz

The Speaker's chair was illustrated in a painting of 1830 by George Catlin, and in 1866 in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. In Leslie's also appeared a print of "the Chair of the Speaker of the Senate," known now as the governor's chair. Looking something of an oddity in this print, it was no doubt the chair a Richmond antique dealer in 1928 offered to sell to Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin, the Bruton Parish minister who was John D. Rockefeller Jr.'s partner in Williamsburg's restoration. By that time it had lost the rounded crest of its back, so its appearance was even odder. Yet its history in the Capitol at Richmond was indisputable, the quality of the carving on its arms and legs was outstanding, and it seemed clearly of eighteenth-century origin. Furthermore, its association with the speaker's chair carried tantalizing hints of its use in the colonial Capitol. Goodwin was too shrewd to let such an opportunity pass, and he acquired the piece for the restoration enterprise.

The most unusual feature of this chair, to a layman, is the height of the seat—nine inches above normal. This, of course, makes the legs distinctively long. Then one notices that the back legs and feet are as fully formed as the front, not attenuated as usual. This suggests the chair was made to stand out from the wall and to be experienced in the round. It needs but the most basic familiarity with the equipage of ceremony to see that this is the throne form, though now missing some distinguishing heraldry and its normal accompaniment of footstool. With this kind of chair it is the height of the seat that elevates the sitter above his surroundings.

It was described in 1866 as the chair of the Speaker of the Senate, the name given to the upper house of the Virginia legislature after independence was won. The colonial counterpart was called "His Majesty's Council," and it met in the Council Chamber of the Capitol, presided over by the governor, the monarch's vice-regent. The throne form was thus entirely appropriate for this function.

All of the accoutrements of the governor's chair as it now appears—the crimson velvet upholstery, the fringe, the brass nails, and the footstool, created by Gusler and Leroy Graves according to comparable eighteenth-century examples—are based on the plentiful documentation surviving from this period of governors' chairs in the American colonies.

What makes the chair exceptional is the brilliant quality of the carving, including the convincing realism of the traditional lions' heads for the arm terminals. Whether it was made and carved in Williamsburg is debatable, but in style it dates from about 1750, so it could have been acquired for the refurbishing of the Capitol after the fire of 1747.

Like the earlier speaker's chair, it was in colonial Williamsburg. Like the speaker's chair, it is what Colonial Williamsburg's curators have long called "a piece of the True Cross."

The Capitol chairs played central ceremonial roles dignified by royal association and hallowed by tradition. The rites associated with them were probably modest compared with the ones in which the remaining two chairs in Colonial Williamsburg's extraordinary group played their parts. These objects are as distinguished for their complexity as for their commanding presence, in the same way that the Masonic rituals in which they were used were noted for their elaborate imagery.

Masonic protocol required a chair for the master of the lodge, sometimes two more for lesser officials. The two grand master's chairs in the Colonial Williamsburg group are among the most ornate in America. Both were made in Williamsburg, the first and earlier one for the local Lodge 6, where it has remained, though it is on long-term loan to Colonial Williamsburg.

This locally made Masonic chair was presented to the Williamsburg lodge. Two inches thick and twenty wide, the back is solid mahogany. - Photo by Hans Lorenz

Tradition connects it with a governor and, interestingly, it features the same lion's head arm terminals as the governor's chair, though not so finely carved.

Whether Lord Botetourt, Virginia's penultimate royal chief executive, presented this chair to the Williamsburg Lodge in the late 1760s, as tradition has it, it was undoubtedly made by a local tradesman, probably in the shop of Anthony Hay on Nicholson Street. It is blazoned with carved motifs, symbols that would have been familiar to the egalitarian group of men who intermingled in this fraternal organization—aristocrat, great Virginia gentlemen, local tradesmen.

It was made to stand on steps—three, according to Masonic codes—thrusting it and its occupant above its surroundings, just as the high-backed Speaker's chair does. Even when it was unoccupied, it was clearly designed to be an object for contemplation, for veneration. Its back, formed from one impressive plank of mahogany twenty inches wide and almost two inches thick, is a virtual lexicon of the Masons' symbols. Surmounted by a beautifully rendered cartouche and arms of the London Company of Masons, appropriately flanked by the rose of England and the thistle of Scotland, the classical orders of architecture stand out amid luxurious foliage, rosettes, and the age-old masons' tools of level, square, plumb, compass, and ruler. Much of the analogy is architectural, of course, linking the Masons to their ancient craft as far back as the temple of Solomon. It is symbolic of all that the Masons held most sacred—right order, skill, beauty, wisdom, and strength, virtue, rightness, and equality. Fundamental to Masonic beliefs are a correct knowledge of God, the recognition of natural laws, and an acceptance of man's harmonious and egalitarian place within the universe.

As impressive as the Lodge 6 chair is in its accumulation of fine detail, it must still yield pride of place to the Benjamin Bucktrout master's chair, the most elaborate piece of Masonic furniture of eighteenth-century America, and the most important piece of signed Virginia furniture known.

All the elements of the grand back are brought into greater prominence and are large and fully developed. The two flanking pilasters support a rusticated arch with a keystone embellished with a scrolled inscription. Above this is a cushion on which would have been set, almost certainly, a crown. Below the keystone is a finely sculpted bust of a man in the typical "undress" of the period, clearly associated with portraits of men distinguished for the creations of their minds and their hands—architects, philosophers, composers, poets, painters, sculptors, and so on. The bust is flanked by the sun and the moon. The tools that were fundamental to the masons' craft, and to the Masons' imagery, are dramatically grouped around the central pilaster and are large in scale. Crossed keys and crossed quills complete the back, rising as it does above the original leather surface of the seat, the handsomely carved seat rail, and the finely detailed front legs in the form of rococo dolphins.

An object with so many specific and recognizable details must have a specific and lengthy story to tell, and this chair does, far longer than space here allows. It is well told in the magisterial catalogue Southern Furniture, 1680¬ 1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection, by the current chief curator, Ron Hurst, and former curator of furniture, Jon Prown, published by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in association with Harry N. Abrams in 1997, where the other chairs examined here are also discussed at length. The tools and the architectural details represent the diverse elements of construction, the increasing levels of skill needed to become truly proficient, and, equally important, all those aspects of right conduct that enlightened and virtuous members of Christian societies should observe and practice.

The sun and the moon rise on the master's chair made by Benjamin Bucktrout, which bristles with a tool chest's worth of Masonic symbols. - Photo by Hans Lorenz

Enlarge Detail 1 Detail 2

Authority was lent the Masons' complex and dignified philosophy by constant reference to the finest creations of antiquity—classical architecture, for example, and classical conduct, summarized by the motto on the arch's keystone, Virtute et Silentio, "by virtue and silence"— and the Bible open to the first book of Kings, relating to the building of the temple of Solomon.

However exceptional and magnificent this chair is, its documented history is sparse. It was presented to Unanimity Lodge 7 in Edenton, North Carolina, on July 6, 1778, by brother George Russell. Tradition within that lodge maintains that Russell was a sea captain who rescued the chair from potential destruction during the Revolution and gave it to the Edenton Lodge for safekeeping. The lodge's records also include references in 1811 and 1815 to requests from Norfolk Lodge 1 that the chair be returned to Virginia, though there is no specific evidence that it was made for that lodge. Nothing came of these requests, and the chair remained in Edenton until it was acquired by Colonial Williamsburg in 1983.

Former chief conservator Carey Howlett supervised the lengthy treatment of this grand chair and made an interesting observation. The five-pointed star, compass, and square placed on the open bible in the center of the back became, within a generation of the chair's being made, the precise form of jewel in Britain for a provincial grand master, one of the highest officers. Shortly after the chair was made in Williamsburg, a distinguished Williamsburg resident was appointed provincial grand master of Virginia—none other than Mr. Speaker, Peyton Randolph. In the summer of 1774, Randolph sat for an important commission in Williamsburg, his portrait in full regalia at full length by Charles Willson Peale, a painter and Mason from Annapolis. Peale had already painted George and Martha Washington and was to paint one of the best of all portraits of Washington in 1780. Peale's portrait of Randolph was duly completed and hung for many years in the Library of Congress before its loss in a fire in the mid-nineteenth century.

Might fellow Mason Benjamin Bucktrout have made this elaborate chair for the eminent Mason, and eminent Speaker, Peyton Randolph? There is nothing to prove or disprove it. It may well be that the distinguished Randolph, soon to be lauded as "the father of our country," is the person who unites in our minds these two thrones made in Williamsburg—the Speaker's chair, the more venerable one, being symbolic of the right of representation in a civil society and the right to be fairly heard—and the Masons' chair, then new, with its plentiful reference to virtue and equality. It is a remarkable story.

Graham Hood, Colonial Williamsburg's vice president for collections and museums and Carlisle H. Humelsine Curator until his retirement in December 1997, writes from his home beside the Chesapeake Bay. His story on Charles Willson Peale's portrait of Washington appeared in the summer 2002 magazine.