Page content

Colonial Williamsburg Carpenters Construct Buildings of the Past

Reproduction Structures Offer Guests Look at Trade, Hands-on Experience

by Ed Crews

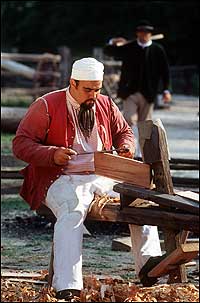

Carpenters building the Peyton Randolph House smokehouse, one of home's outbuildings, in 1997 - Photo by Tom Green

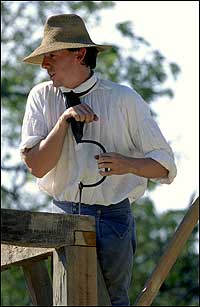

Colonial Williamsburg carpenters build by hand each eighteenth-century structure they reproduce for the museum's 301-acre Historic Area. Using authentic tools and centuries-old skills, the tradespeople frame walls, raise rafters, lay floors, and hang doors. Muscle is as essential as skill. No matter how hot and hard the work, though, the costumed interpreters seldom labor alone. Guests often pitch in. Some drive nails or plane boards. Others work in the sawpit, cutting logs into lumber. Occasionally, a group helps raise a wall.

Although there are some limits-no guest can use an ax or chisel-the carpenters' work yard behind the Peyton Randolph House offers as many opportunities for hands-on learning as any craft site in Colonial Williamsburg. This approach to education and interpretation is long-standing. It also connects powerfully the past and present.

"I really enjoy it when I can see that a group that I'm talking to, whether it's a school group or a group of guests, is enjoying its time and learning in the process. When we have someone from a school group do a little sawing with us, I feel it's an experience that will stay with them for a long time," said Ted Boscana, a journeyman carpenter.

Garland Wood, master carpenter, said: "People are surprised and delighted to get a chance to participate in our work. Guests are most interested in our tools and eighteenth-century building techniques. They're fascinated, too, to learn how much colonial and modern carpenters have in common, whether it's tools, skills, or challenges."

The carpentry crew is one of the largest trade groups in Williamsburg. The team includes Wood; two journeymen, Noel Poirier and Boscana; and four apprentices, Bobby Clay, Corky Howlett, Jack Underwood, and Wes Watkins. The men enjoy their work. Yet their main aim never is simply to build a barn or a kitchen. Instead, every project is a way to teach guests, to test ideas about colonial carpentry, and to keep the craft alive. Roy Underhill, Colonial Williamsburg's first master housewright, wrote: "The carpenters want to preserve the process as much as the product of that labor."

Carpenters read eighteenth-century building manuals and review period documents. Research often is a team effort drawing on the knowledge of other Colonial Williamsburg crafts and disciplines, from archaeologists and curators to blacksmiths and brickmakers.

But, Wood said, "there is no substitute for looking at a real colonial structure. You can still see tool marks, chalk lines, and pencil marks. The buildings are a real legacy, if you know how to read them."

During the past two decades, these readings and other research have had a direct and immediate impact on the accurate reproduction of Williamsburg buildings, including slave quarters, a chicken house, a privy, the Anderson forge, and a tobacco barn. The team is working on its most ambitious project-the re-creation of eight buildings, including a smokehouse and kitchen, behind the Peyton Randolph House.

Besides informing construction of these projects, historical research also has provided a clear view of the colonial carpenter's life, business practices, and standing in society. Interpreters now know that Colonial Virginia carpenters typically fell into three groups:

Clapboard carpenters built common structures in the countryside, like homes and tobacco barns, that required simple skills.

African American carpenters often were slaves trained by masters. Slave labor helped ease the colony's shortage of skilled workmen. Slave carpenters usually knew the skills of the clapboard carpenter. Slave carpenters often were hired out.

Accomplished carpenters worked on the most complex projects.

The colony's finest craftsmen could cut wood with axes, saws, and chisels. They could plane boards, drill holes, and keep everything level and tight.

"I think the most interesting thing I've learned about eighteenth-century Virginia carpenters is the diversity of their work," Boscana said. "In England, with an abundance of skilled men in the trades, it seems the only way to avoid excessive competition was through a specialization of their work. In Virginia, the work varied from the framing, flooring, roofing, and siding of houses to more decorative work of moldings, wainscoting, raised paneled doors, sash, and even simple furniture."

Carpenters labored hard. Workdays ran from dawn to dusk. To save time and effort in an age of hand tools, carpenters always put their "best face to London." That meant, for example, that visible floorboard was smooth and attractive. The underside, however, was left rough, saving time and effort.

Some colonial carpenters became entrepreneurs. Besides having craft skills, these men needed enough math to measure, estimate jobs, and handle business transactions. They had to read and write. This allowed them to keep records, to understand contracts, and to draw ideas from period manuals like The Builder's Dictionary and The Builder's Jewel, or The Youth's Instruction. The most ambitious carpenters, men like Benjamin Powell, could succeed in business and rise in society. Powell has been called Williamsburg's most successful colonial carpenter. Guests can see his home, and his handiwork at Bruton Parish Church. Powell rose from carpenter to gentleman in the third quarter of the 1700s. He ran a thriving business, filled important civic positions, and participated in Revolutionary War activities.

Powell and his contemporaries had a homebuilding process similar to today's. In town, a carpenter had to comply with building regulations. He worked with subcontractors, like masons and painters, and suppliers for products ranging from lumber to shingles. A good master carpenter with an experienced crew could complete a typical Williamsburg home in about a year. That speed is impressive considering that everything from the foundation to bricks, boards, window frames, and nails was handmade.

By the late 1700s, completely handmade homes were about to vanish, however. Factories during the 1800s produced a huge and varied array of construction supplies and prefabricated components. Any vestige of handcrafting virtually disappeared in the twentieth century because of power tools.

One aspect of the builder's trade, past and present, will be evident-the joy of creation on a grand scale.

"For me, the best part of my job is that at the end of the day I can look back at the site and see what the crew has accomplished," Howlett said. "It's right there, and it's real. Very few people have something tangible, something you can touch at the end of the workday."

Richmond writer Ed Crews is the author of a long-running journal series on colonial trades.

Learn more: