Page content

Online Extras

Zoom in on Mesoamerican Calendars

Library of Congress

Some believe the Maya calendar predicted the end of the world on December 21, 2012, closing a 5,137 year cycle. Alignment of the sun and the center of the Milky Way foretold the violent destruction of earth.

Library of Congress

An Aztec priest sacrifices a human heart to the gods for their continued protection.

Library of Congress

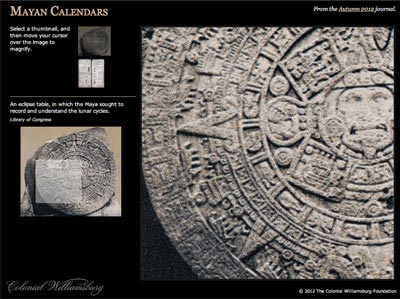

An eclipse table, in which the Maya sought to record and understand the lunar cycles.

Library of Congress

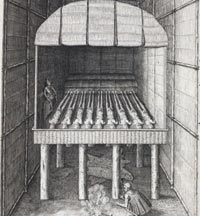

De Bry’s illustrations of a tomb of Powhatan chiefs, which prepared bodies for the afterlife.

Beginnings and Endings:

Of the Maya and the Milky Way, Powhatans and the Giant Hare, Prophecies and Time

by Anthony F. Aveni

We live in prophetic times. Hundreds of books and thousands of websites foretell the coming Doomsday: December 21, 2012, the winter solstice. Y12 prophets, as I like to call them, say it is all written down in the Maya inscriptions. These ancient Americans set the end of time according to an alignment between the sun and the center of our Milky Way galaxy, which they viewed as the “womb of creation.” On that day the great odometer of time known as the Long Count, a 5,137 year cycle, which began August 11, 3114 BC, terminates, bringing with it the destruction of the world through violent earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, a sudden overturning of the earth’s magnetic field, a planetary lineup, a collision of the earth with an asteroid, and other apocalyptic events, depending on whom you believe. Other Y12ers disagree. They contend that ancient Maya wise men told of a 2012 bliss-out rather than a blowup, a sudden elevation of all human consciousness to a higher dimension of universal love and compassion in which humanity will reject all temptations of the selfish, materialistic technoworld and reacquire its true cosmic heart.

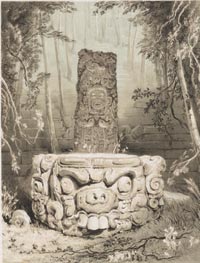

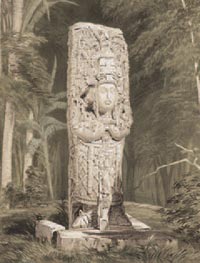

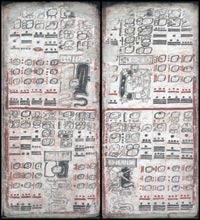

In 2009, after many worried Internet browsers wrote me inquiring whether I thought any of these prophecies might come to pass, I wrote a book explaining why, based on scientific evidence, it is extremely unlikely that such cataclysmic changes could take place. I also discussed the evidence in the Maya historical record about the end of the world. Anyone who carefully reads the Maya hieroglyphs will know that the ancient Maya held no view, either of world destruction or a sudden transformation of human consciousness. Hundreds of Maya carved stones, or stelae, found throughout the ruins of Copan, Palenque, Tikal, and elsewhere, portray effigies of rulers, recounting their accessions, conquests, marriage alliances, deaths, and transfers of power to their offspring. The monuments disclose little about the future, near or distant. Rather, they are past directed, serving as a means of legitimizing the right to rulership by forging connections between dynastic heritage and mythical ancestors who created the world. Furthermore, the inscriptions say nothing of an alignment with the Milky Way, nor do they connect the cosmos to any part of the female anatomy.

When the Maya set up their Long Count about three millennia after the zero date, they had no celestial event in mind, either for the beginning or ending of the Long Count. More likely, as in our own calendar, they reckoned it from a date that possessed historical significance in their culture. Still, tens of thousands of believers tap into fabricated Y12 prophecies about the end of time. Having thought a lot about it, I have come to realize that the way of acquiring wisdom about the future of humanity, based on revealed knowledge from the prophets of the cyberworld, and my own, based on reasoned evidence, are truly irreconcilable.

We have always lived in prophetic times. America has had a long love affair with apocalyptic world endings. Our earliest colonizers did not cross the ocean out of mere curiosity. They set out to find a place where they could practice forms of religion that lay well outside the mainstream in Great Britain and northern Europe. As James Breig’s accompanying article on page 52 suggests, contemporary forecasts about the impending end of the world might not have seemed so out of place in the America of a few centuries ago.

Look for the signs in nature—a comet, the seething of a volcano, a dramatic vision of the northern lights. So warned the prophets during the Great Awakenings from 1730 to 1750 and much of the early nineteenth century, periods in colonial and national history marked by intensely emotional religious fervor and extraordinary anticipation that Christ was about to descend to earth and proclaim the kingdom of heaven. Those who had renounced all sin and accepted him as savior would be carried off to heaven and life eternal. All others would spend the hereafter in hell.

If we contrast colonial ideas about time’s beginnings and endings with those of the native people on whom the foreigners infringed, once again we encounter irreconcilable views. For example, the Christian God makes man to be only a little lower than angels: “Thou madest him to have dominion over the works of thy hands. . . . All the sheep and oxen, yea, and the beasts of the field,” as Psalm 8.4–8 says. In the religions of Native America, God is replaced by a multitude of nature deities, each ruling its particular domain. For the natives, a bond between human and animal spirit prevailed in a world in which man was not given dominion over all four-legged creatures. Moreover, their world was not a place where goodness would go unrewarded here on earth, with the imbalance righted in the hereafter. Rather the Indians thought the world a place they were required to help keep in balance by replenishing it through cycles of human action. Thus, they offered sacrifice as a kind of debt payment to the gods, who, in return, nurtured them by providing nature’s bounty.

Virginia’s Powhatans told their early English inquisitors that the great god Ahone had made the sun, moon, and stars. They made offerings to the sun at the beginning of each season; thus, they gave part of the first fruits of the harvest to the sun as well as to their rulers, who, they believed, had descended from the sun. They made similar offerings to the full moon at the start of the hunting season. Okee was a less-predictable god of whom they had to be wary. One informant said he is present always “in the Air, in the Thunder, and in the Storms.”

For all these woodland people, nature deities played a hands-on role in setting the stage for human activity. For example, the imaginative Patawomecks, another spelling of Potomac and one of eleven recognized Virginia tribes, believed men and women were created by a god that took the form of a giant hare. He kept them in a bag where he dwelled, in the direction of where the sun rises. But the four gods of the winds threatened to eat the hare’s creations. The hare drove them away; then he created the water and the fish to live in it along with the land and a great deer to live on it. The four winds returned, killed the deer and ate it, whereupon the hare plucked all the hairs from the discarded deer carcass and spread them over the earth. Every hair became a deer. Only then was the hare ready to open the bag and spread the men and women about the countryside, where they would have plenty to eat.

The neighboring Cherokee thought the world was formed when a giant water beetle lifted mud to the surface of the sea. The mud grew to become the earth. The animals, who had previously lived in the sky, made their homes on the newly formed earth, to be joined later by men and women. According to one version of the story, after years of harmony humans and animals came into conflict. Humans began to kill animals for food without paying them respect. The animals revolted by inflicting diseases on the people. The plants responded by giving good medicine to the people. Note that there is little that distinguishes humans from animals in these stories. Both, for example, are organized into tribes, with chiefs and councils. Above all, natural phenomena play a major role. There is no single creator god, nor even a single timed creation, as in Genesis.

The invaders did not appreciate and often misinterpreted the native viewpoint. Such inquisitive colonists as John Smith often mistook the act of sacrifice as a superstitious practice indulged in by idol-worshipping, god-fearing savages who gave offerings to appease angry deities. For example, Smith tells us that during storms the Indians would “after many hellish outcries and invocations . . . cast tobacco, copper, puccoon [a plant dye], etc. into the water to pacify that god whom they think to be very angry in those storms.” Left out of the description is the native belief that being bound to nature in all its varied forms entails acts of reciprocity, namely the offering of something precious to restore the balance of nature. Unlike the Christian belief in a day of judgment to end all time, for the native time never ends because people keep the endless cycles of the seasons alive. They participate in their cosmology.

When the Jamestown English ransacked Powhatan temples, they reported finding tightly rolled, sewn-up bundles or mats. Ripping them open, they found “some vast bones of men . . . and images of the god Okee.” There were rib cages nailed to boards and separately packaged arm and leg bones, all clad in colored cloth. Powhatan remains are few, but large numbers of buried boxes among other Atlantic coast and southeastern tribes have survived predation by the white man, as do descriptions of some of the burial rites that attended them. In a well-known Cherokee rite, relatives immediately washed the newly deceased’s body while women sang a song of lamentation over it and men dabbed their foreheads with ashes. A brother or sister thoroughly washed the body with a dissolved herbal mixture before burying it. Often the corpse would be placed in a tightly flexed position in a pair of overlapping wooden containers piled high with stones in an underground pot. Among the items found in burial boxes were bowls of food, shell rattles to scare away offending spirits, beads and gorgets made of shell. After seven days of mourning, a priest would purify the house of the deceased. He would light a new fire in the hearth and brew a special tea for the family to drink.

Given the elaborate purification rituals they conducted, it seems clear that the natives took the matter of what happens to us after we die seriously, though they seemed to require no god to pass judgment on human life. What transpires in the afterlife, what we refer to as time’s end, also stands in sharp contrast with colonial beliefs.

What awaited the Powhatan in the afterlife? The English heard varying accounts, but they colored the stories with their own beliefs. Thus, John Smith tells us that when tribal chiefs died they went, with their ancestors, in the direction of the setting sun. They would follow a bridge to the sky. There they would live in a garden of delight dining on delicious fruits, singing, dancing, and never having to labor. Finally they would dissolve and die, to be born again to experience another life on earth. Ordinary people, Smith reports, suffered a far worse fate: they rotted in their graves for eternity. It was the elite who informed Smith of their status in the next world. He also tells us that the Indians believed in a supreme creator and a devil-like counterdeity. Note the Christian overtones in these characterizations.

Smith was noted for asking leading questions, often mixing in English with native concepts, fully anticipating the answers he would get. A lesser ruler of the Patawomeck told a more reliable inquisitor that departed souls traveled a path toward the west lined with berries and fruits. There they arrived at the home of the hare god, where they reunited with their forefather, grew old, died, and were reincarnated on earth. There was no mention of a heaven or a hell, or any notion of the good versus bad afterlife. Okee, the informer said, had punished the wicked enough right here on Earth. Be successful and live the good life while you reside in the present world seems to have been their motto.

The idea of the Path of Souls is widespread throughout the Americas from Alaska to Peru. For many Native American tribes, including the Maya, the roadway of choice is the Milky Way. The place where that luminous white band intersects the horizon is said to be the start of the soul’s journey. It shifts back and forth from north to south along the eastern and western horizon throughout the night as well as through the seasons. Central Algonquian people believe that the soul remains in the body after burial and purification, which explains all the attention to detail in the preparation of the corpse. Then, on the day of the Feast of the Dead in late autumn— our Halloween—all the souls are released to make their journey toward the west after sundown, ascending the star-spangled ladder before the onset of winter. The Cherokee go further: they identify the bright stars Sirius and Antares as dogs that guard the places where the Milky Way crosses the horizon. The dead are instructed to bring enough food from their burial offerings to feed the dogs lest their passage be impeded.

Where did we come from and where shall we go? These are basic questions about human existence with which every culture since Paleolithic times has grappled. On the American frontier a few centuries ago, two cultures in collision proffered different answers. For the colonists, an all-powerful, beneficent God who created us in his image offered eternal life for those who repented of sin. For them an eternity of rapturous bliss lay just around the corner, for prophecy had declared the descent of the savior from heaven to be imminent. For the natives there was promise too. Their souls would climb to heaven along the Milky Way, the celestial road of the dead, then get another chance at life here on earth.

If you think about it, maybe these two ways of thinking about life’s beginnings and endings are not all that different. As for the wished-for transformation of human consciousness that colors so many contemporary 2012 prophecies, if thinking about a better world in the future could be replaced by acting in ways to make it better, then we, like those who preceded us on this continent, might also become participants in shaping the course of time.

Anthony F. Aveni is Russell Colgate Distinguished University Professor of Astronomy, Anthropology, and Native American Studies at Colgate University. Among his latest works on Native American culture are two books for children: The First Americans: Where They Came From and Who They Became (Scholastic, 2006) and America’s First Great Cities (Roaring Brook, 2012).

Suggestions for further reading:

- Anthony F. Aveni, The End of Time: The Maya Mystery of 2012 (Boulder, CO, 2009).

- George E. Lankford, Reachable Stars: Patterns in the Ethnoastronomy of Eastern North America (Tuscaloosa, AL, 2007).

- Helen C. Rountree, The Powhatan Indians of Virginia: Their Traditional Culture (Norman, OK, 1989).