USMA

In a 1928 town meeting, former major turned school board chairman, Samuel Freeman opposed Williamsburg’s restoration and lost.

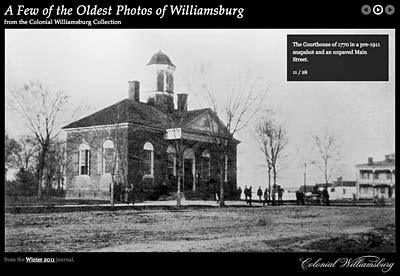

Colonial Williamsburg

Williamsburg High School before it was demolished to make room for the Governor’s Palace.

National Archives and Records Administration

Lieutenant Freeman, far right, served in the Tenth Cavalry of the African American Buffalo Soldiers, in Arizona in the 1880s.

Colonial Williamsburg

Abruptly banishing this Confederate monument from the historic colonial-era Palace Green angered townspeople.

Colonial Williamsburg

Freeman and his family lived in and, in 1928, sold to Dr. Goodwin their Historic Area home on east Francis Street.

The Man Who Said No

by Rosanne Thaiss Butler

Mass Meeting, 8:00 p.m., June 12, 1928, Williamsburg High School on Palace Green. Seventy-year-old retired army Major Samuel D. Freeman, chairman of the town’s school board since 1924, arrived early. The city council had called the meeting to discuss a “proposal to convey the properties of the city to Dr. Wm. A. R. Goodwin and his associates” and “to give a chance for questions for free and frank discussion by citizens.” This evening, Goodwin would reveal to the town the identity of the benefactor who’d spent millions on 140 private properties Goodwin had bought in Williamsburg since 1927.

Sam Freeman was about to give Williamsburg something to think about.

Who was Goodwin, why were city properties up for transfer to him, and what had it to do with Freeman? First, the Reverend Dr. William Archer Rutherfoord Goodwin and the transfers.

Professor of religion and endowment campaign director at Williamsburg’s College of William and Mary and rector of Bruton Parish Church, the minister had long been interested in historic preservation. He had during a stint at Bruton from 1902 to 1908 restored the building to a colonial appearance, dreaming even then of returning the town itself to the elegance it had enjoyed as a colonial Virginia capital.

In 1909, he'd become rector of wealthy St. Paul’s in Rochester, New York, where he honed his fundraising skills. He returned to Williamsburg in 1923, persuaded by William and Mary President J. A. C. Chandler to work for him raising money to revitalize the deteriorating college. Goodwin’s plan was to obtain and preserve historic Williamsburg properties for the use of the school as housing and classrooms. He began seeking donors.

In 1924, he approached philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr., who in 1926, the year Goodwin returned to Bruton’s rectorship, underwrote Goodwin’s first purchases of Williamsburg property, the George Wythe House and the Ludwell-Paradise House. Rockefeller asked that his involvement be kept secret. In May 1927, Rockefeller gave Goodwin the go-ahead to buy more private properties. In November, Rockefeller committed to Williamsburg’s full colonial restoration, earmarking $5 million for the project that would become Colonial Williamsburg.

Restoring the town–tearing down the new and rebuilding the old–meant that Goodwin had to acquire the city-owned greens and the modern buildings on them. The greens were where some of the most significant colonial buildings, including the Governor’s Palace, had stood. For months Goodwin, the Rockefeller organization in New York City, Williamsburg and Virginia state officials, and architects and others hired for the project worked through organizational, financial, legal, and technical details. Goodwin drafted an agreement that obligated his associates to build a new courthouse, jail, firehouse, and other facilities for the town in exchange for transfer of the Palace, Courthouse, and Powder Horn Greens. The city fathers accepted it subject to approval by vote of the citizens. Rockefeller, heeding Goodwin’s advice that townspeople were likelier to consent to transfer of town property if they knew to whom, decided his identity as donor should be announced.

Before the mass meeting, Goodwin publicly circulated his proposed agreement. As meeting time approached, he was confident of approval. He had carefully planned the night’s agenda, and city elections earlier that day had elected as mayor and to the city council men friendly to the proposed restoration.

Elizabeth Hayes, Goodwin’s secretary, recounted the evening’s events in her manuscript The Background and Beginnings of the Restoration of Colonial Williamsburg.

Proceedings began with the election of mayor elect John Pollard as chair. City Council President Channing Hall read the agreement aloud. Goodwin spoke of his and his associates’ intention “to make this favored city a shrine . . . dedicated to the lives of the nation builders,” and answered questions. At last, to hearty applause, he named Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller Jr. as the Restoration’s donors.

What happened next was not part of Goodwin’s script.

Sam Freeman got to his feet and, in a “clear, firm voice with oratorical gestures,” spoke his mind:

It is my unpleasant duty to voice the minority side. There should be something said for both sides. No consideration has been given to the broader aspects of this transfer. If you give up your land, it will no longer be your city. Will you feel the same pride in it that you now feel as you walk across the Greens, or down the broad streets? Have you all been hypnotized by five million dollars dangled before your eyes? Can any of you talk back to five million dollars?

If we close the contract, what will happen when the matter passes out of the hands of Dr. Goodwin and Mr. Rockefeller, in both of whom we have perfect confidence? Who will be the head? Who will control? I beg you to consider some things which have been overlooked. Dr. Goodwin has spoken very beautifully and very poetically. But is this a philanthropic enterprise? Is it altruistic? There is no doubt but that the contract will go through, but I want you to know that there is one man who has had something to say on the other side. We will reap dollars, but will we own our town? Will you not be in the position of a butterfly pinned to a card in a glass cabinet, or like a mummy unearthed in the tomb of Tutankhamen?

When Freeman finished, “there was perfect silence.”

However stunning Freeman’s remarks had been, 150 voted in favor and four against: Freeman, Dora and Cara Armistead, and outgoing mayor John Henderson. The next day, James City County citizens, included because they shared the courthouse with the city, voted unanimously for Goodwin’s proposal. June 14, the city council and the county board jointly adopted a resolution thanking Rockefeller and Goodwin. The Restoration moved forward.

Now, Freeman. Born in 1858 in nearby Mathews County, he had lived in Williamsburg with his family since 1922. He'd seen a bit of the world before landing in this small town. The red-haired son of Confederate veteran Joseph Freeman—Sixty-first Virginia Regiment— and his wife, Mary Diggs, attended the Virginia Agricultural & Mechanical College, now Virginia Tech, in Blacksburg. He matriculated at the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1879 and graduated seventh in a class of fifty-two in 1883 with high marks in mathematics, science, and engineering. West Point Superintendent John Wilson said Freeman was “of high character, a courteous gentleman and an efficient officer.” He stayed in the army for more than thirty years.

His assignments and efficiency reports indicate that he was a talented administrator and instructor. From 1883 to 1887, Lieutenant Freeman served as an officer of the Tenth Cavalry, the African American Buffalo Soldiers–so called by their Indian foes for the soldiers’ ferocity and the texture of their hair–stationed in Texas and Arizona near the end of the Indian Wars. For the next decade, Freeman taught mathematics, astronomy, and natural philosophy at West Point. An inventor, he patented a portable folding bathtub the cavalry used.

When the Spanish American War came, Freeman resumed service with the Buffalo Soldiers and was promoted to captain. He went with them to Cuba, where he contracted malaria, then to Fort Robinson in Nebraska, and to the Philippines. In 1907, he was promoted to major and married a twenty-nine-year-old teacher, Bertha Meier, whom he'd met out west.

In August 1909, Freeman retired, returning with his wife to Mathews County. The first of their three children was born in late 1909, the last in 1913. During World War I, Freeman volunteered to return to duty. First assigned to teach military science at West Virginia University, he later commanded the Students’ Army Training Corps, a federal effort to teach draftees skills needed for the war, at Alabama State Normal School and at The Citadel military academy in Charleston, South Carolina.

Promoting the war effort in Mathews County, he spoke at its 1917 Patriotic Rally, addressed 5,000 at its 1918 Fourth of July celebration, and was commander of Post 83, American Legion.

Freeman moved his family to Williamsburg because he thought its schools better than Mathews County’s. The Williamsburg of the 1920s was a clash of old and new. H. M. Stryker, mayor in the 1950s and ’60s, said downtown before the Restoration was “all strung out, from the college to the site of the old Capitol. Banks, stores, rooming houses, and meat markets mixed in with buildings left over from the eighteenth century.” Elizabeth Hayes found its colonial buildings and gardens charming, “marred but not destroyed by the devastating touch of time.” Goodwin hated its unsightly telegraph poles, falsefront shops, gasoline stations, and jerrybuilt Palace Theater.

Freeman bought the Wise House at 432 East Francis Street for $5,000 from Virginia Peachy Wise. Freeman sold the home to Goodwin in March 1928, leasing it from the Restoration until moving out four years later. Freeman was Williamsburg’s school board chairman for six years and a Bruton vestryman for five. He was part of the three-man vestry committee that in 1926 asked Goodwin to resume Bruton’s rectorship.

For the Governor’s Palace at the north end of Palace Green to be reconstructed, the property had to be cleared of the city’s high school and the college’s Matty School, a teacher training facility. For months, Goodwin had strategized the site’s transfer to the Restoration. In March 1928, the college told Goodwin he had its full cooperation. Since the school board controlled Williamsburg High School and Freeman was board chairman, Goodwin had to deal with him, too.

Days before the mass meeting, Goodwin approached Freeman, asking him to develop with college president Chandler an understanding on possible transfer of the schools sites and replacement of the buildings. Shortly after the meeting, Freeman said that the school board and the college would cooperate in operating the schools only so long as that was in the interest of both.

As for the high school, he said, “It is not to be expected . . . that the School Board will be moved to relinquish its rights for anything less than what it considers due to the city in the present circumstances and, at the same time, commensurate with the dignity of your undertaking.”

That did not sit well with Goodwin. He advised Freeman to consult an attorney, and wrote to the school board as a whole, reminding them that he had the backing of the mass meeting agreement and other authority. He asked them by formal vote to consent to transferring the high school and site, and “authorize the proper person” to relinquish the board’s rights in those holdings.

Goodwin said the Restoration would build either a school for the city’s and the college’s shared use, or a city school to run without college involvement. Freeman notified Goodwin that the board accepted the first option. Eventually, the Restoration decided to pay the school board and the college $200,000 for their holdings, the board and the college to handle construction themselves. Another $200,000 toward the new school came from the General Education Board, a Rockefeller philanthropy, and the state of Virginia.

Work began in autumn 1929 on the Matthew Whaley School, named for a seventeenth-century boy whose mother created in his memory an endowment for educating Williamsburg children. Freeman oversaw city interests throughout the project.

Freeman’s opposition at the mass meeting didn’t damage his good standing in Williamsburg. He met his official responsibilities. Rawls Byrd, city superintendent of schools during Freeman’s tenure, said Freeman was greatly interested in his chairman duties and spent much time on them.

The September 19, 1930, Virginia Gazette, the local newspaper, reported that at Whaley School’s opening ceremonies that week, college president Chandler “paid a well-deserved tribute to Major Freeman for his work on behalf of the city schools and education in general.” The school’s auditorium was dedicated to Freeman. The bronze plaque that still hangs there says that his “faithfulness and efficiency in attending to public duties have contributed in a large measure to the success of this school.”

When Freeman resigned as school board chair in December 1930, the city council accepted his departure “with reluctance,” and the school board told him it felt

That your wise counsel, your willing service, and your high ideals have been of inestimable value to Williamsburg and this community. That such a fine spirit always existed among members of the Board has been due in great measure to the character of your leadership.

In 1932, the Gazette remembered him as “the progressive and efficient chairman of the city school board.”

Freeman opposed Goodwin’s plans because he thought the Restoration would alter everything likeable about Williamsburg. In his sixties, after a peripatetic life, he’d chosen to live in this quiet college town, and had a perspective different from many who had lived in Williamsburg all their lives. Freeman saw that he and the town had something to lose.

Freeman moved back to Mathews County in 1931. Their children were grown, the new public school was completed, and he was eager to return to his rural retreat, Avoca Farm, named for his wife’s Iowa hometown. Freeman died in 1948 at eighty-nine and is buried in Mathews County’s Trinity Cemetery.

What of his mass meeting question? Did the people of Williamsburg lose control of their town? Sometimes so it seemed. Goodwin himself worried about town reaction to “Northern architects, Northern builders, Northern money.”

As the practical effects of restoration began to be felt, problems arose. Williamsburg attorney and city official Vernon Geddy, who had assisted Goodwin with his purchases of town properties and would have key positions in the Restoration, outlined a troubling situation in a September 1929 letter to Charles Heydt, manager in the New York office of Rockefeller’s real estate holdings.

Geddy said townspeople had great confidence in Goodwin. But they began to have doubts about the project when outsider Robert Trimble arrived in 1928 as construction superintendent. Trimble didn’t understand the townspeople, and they in turn saw Trimble’s authority as conflicting with Goodwin’s, who they’d thought was in charge in Williamsburg.

Matters worsened when the Restoration took insurance business away from local agents and placed it with another newcomer, Robert Lecky Jr., a Richmond fire insurance agent brought to Williamsburg on a one-year contract in 1929 by the New York office to manage its local real estate interests. That cost local people their livelihoods, alienating them, their families, and friends. Geddy said townspeople resented Lecky’s appointment. He “came to this city unliked and suspected,” and his lack of cooperation with Goodwin caused friction.

The Restoration looked to some in town like an unorganized collection of disparate groups “who function in quite evident unharmonious discord.” Residents saw little hope for the Restoration’s success, Geddy said, unless the situation changed.

Improvement came in November 1929 when Rockefeller named Kenneth Chorley the Restoration’s vice president, opening a Williamsburg office in December. Described by Restoration architect William Perry as “energetic, keen . . . and realistic,” Chorley had worked for Rockefeller since 1923 and been involved with the Restoration early on. Goodwin himself welcomed Chorley’s appointment, telling Rockefeller in early 1930, “An atmosphere has been created of confidence and good-will.”

Public dissatisfaction flared again in January 1932, when something happened that likely would not have, absent the Restoration. Restoration workmen abruptly removed from the foot of Palace Green the town’s Confederate monument, erected in 1908 by the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the citizens of Williamsburg and James City County. It was trucked to the city cemetery on the outskirts of town.

The Restoration hadn’t initiated this move. The town’s UDC chapter did that, with city council approval. The iconic Civil War memorial had become anachronistic, blocking the clear, colonial-era view across Palace Green. Angry citizens asked why the public hadn't been consulted. Some blamed the Restoration. “Indignation . . . began crystallizing” January 21 at Palace Green, said Newport News’s Daily Press the next day, “when a cross draped in mourning was erected on the spot and a sign beneath it bore, in letters of flaming red, the words ‘Crucified on a Cross of Treachery.’”

Reacting to the outcry, the UDC proposed raising the monument on the grounds of the courthouse the Restoration had just built in town; city and county governments agreed. When public opposition persisted, the UDC petitioned the circuit court for help. Judge Donald Halsey found in April that since the city and county had agreed to the UDC’s moving the monument, all possible owners had assented. The monument was moved to the new courthouse, to be relocated twice more before coming to rest in 2000 in a city park behind Colonial Williamsburg’s DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum.

Restoration at its worst meant ongoing upheaval, obliteration of the familiar, and outsiders’ deciding where residents’ houses, shops, schools, and churches should be. On the other hand, the city retained ownership of streets, and Rockefeller’s organization mitigated the disruption restoration caused.

Though the Restoration demolished the high school, built in 1921 for about $90,000, it made possible the $400,000 Whaley School that Rawls Byrd called “the finest school building Williamsburg had ever had.”

It removed businesses from where they had been, but created a state-of-the-art business block, today’s Merchants Square, to accommodate them.

Initial restoration activity concentrated on the Capitol, the Palace, and Duke of Gloucester Street. Owners of houses like Freeman’s, which had low priority because distant from the restoration locus, could sell their homes–Freeman cleared $15,000 from the Restoration on his–and stay as renters until the property might be restored.

For the colonial houses targeted as restoration priorities, Goodwin devised life tenure as a sales incentive for owners, most of whom were elderly and had lived in their homes for years. Life tenure allowed them to remain in their restored houses for life, paying a tiny rent and accepting certain terms. For those whose homes had to be demolished or moved, the Restoration built new or relocated existing ones. Hayes said many who gave up their houses came to Goodwin’s office expressing appreciation for the Restoration, the inconvenience of moving balanced by pride in being part of a “patriotic endeavor to which they were closely related.”

Chorley became Restoration president in 1935 and remained so for twenty-three years, bringing stability and growth to its programs. Townspeople took jobs with the Restoration, becoming part of it.

Rockefeller, a regular visitor to Williamsburg since 1926, bought Bassett Hall on Francis Street in 1936, living there seasonally each year. His affection for the town and his neighborly presence fostered townspeople’s acceptance of the Restoration.

What had been the unsettling new gradually became the comfortable norm. The town adjusted to change; it wasn’t subsumed. It moved and flourished beyond the confines of its old footprint, Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area.

Williamsburg, Virginia: A City before the State, published by the City of Williamsburg to celebrate its 300th birthday in 1999, said: “The area’s long history is one of development and change. Williamsburg in 1975 was vastly different from Williamsburg in 1925, just as 2025 will be greatly different from 1975.”

The man who said no, Sam Freeman, is long departed. But history remembers his life and his stewardship in a city that turned back time.

Rosanne Thaiss Butler is Colonial Williamsburg’s director of archives. This is her first contribution to the journal.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Rawls Byrd, History of the Public Schools in Williamsburg (Williamsburg, VA, 1968).

- Will Molineux, “A Night Fraught with Possibilities,” Colonial Williamsburg Journal, 24, no. 1 (Spring 2002).

- ___, “The Agreement,” Colonial Williamsburg Journal, 23, no. 4 (Winter 2001–2).

- Parke Rouse Jr., The City That Turned Back Time: Colonial Williamsburg’s First Twenty-Five Years (Williamsburg, VA, 1952).

Extra Image

Colonial Williamsburg

The restoration agreement between the City of Williamsburg, the Board of Supervisors of James City County, Colonial Williamsburg, Incorporated, and Williamsburg Holding Corporation, June 14, 1928.