Page content

Online Extras

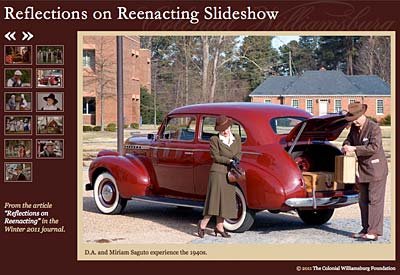

Reflections on Reenacting Slideshow

J. Hunter Barbour

Neal Thomas Hurst re-creates a 1932 Bonus Army soldier marching on Washington, demanding help for World War I veterans.

J. Hunter Barbour

The author and wife, Miriam Saguto, in the guises of a World War II British Home Guard and his Home Guard Auxiliary driver.

Colonial Williamsburg’s annual “Under the Redcoat” program finds a British Army laundress on Palace Green.

Randolph Davis, as a company drummer of the 71st Regiment (Fraser’s) Highlanders, circa 1780, takes a swig of grog.

Reflections on Reenacting

Seeking an Authentic Past in a Specious Present

by D.A. Saguto

There is an element of escapism involved in dressing up like dead people, and playing make-believe, escapism in which J. R. R. Tolkien, he of Lord of the Rings, saw “an attempt to figure a different reality” and found emancipation. Perhaps that’s part of why people spend spare hours outfitting themselves in the garb and gear of this or that historical era and pass spare weekends fighting old battles, reveling in renaissance fairs, or just hanging out with pals who share their affinity for a past. The most serious of them have as well an abiding interest in the fine points of history, a dedication to authenticity, and a determination to come as close to living in yesteryears as they can contrive. We call those folks reenactors.

Understand at the outset that there is a distinction between reenactors—like the blue and gray clad skirmishers mock battling Gettysburg—and professional interpreters and tradespeople employed at such historical museums as Old Sturbridge Village and Colonial Williamsburg to work in costume, to preserve knowledge of the past, and to share it with guests. Museum people do it for a living. The best of the reenactors take their avocation—The Hobby, they call it—as seriously as their work, but, to be candid, others are out there for fun. That said, know that there are interpreters in the ranks of reenactors. Even craftsmen skilled in antique trades, and among them once was me. That was back in the day, and I was one of the serious ones.

Now, I’m Colonial Williamsburg’s master boot and shoemaker, hired a career ago to present an eighteenth-century tradesman, train apprentices up to journeymen, and to practice and to demonstrate the art and mystery of turning leather into footwear. In the 1980s, you might have found me passing weekends outfitted as a seventeenth-century musketeer or uniformed as an eighteenth-century highland soldier or cast in the khaki of a World War II lieutenant or wearing the pleated-pants suit of a 1930s clothes horse.

It’s not always as much fun as it sounds. You’ve lived the definition of discomfort when you’ve stood under a Virginia summer sun in armor, a leather jerkin underneath, and a steel helmet on your head. Or when you and the rest of the Saint Maries’ Citty Militia, in full kit, sweating and sun-reddened, board a ship like the replica seventeenth-century Dove to slip down Maryland’s Saint Maries River and bear away for the Potomac.

That was a sultry June weekend in the 1980s. The ship’s company herded us below like unwanted cargo, and scampered into the rigging to set sail. We had come up for air and sat on a hatch grating to take a meal, when out of the west came a storm wall of turbid grey as high as heaven to drive us back below. The tempest washed waves and foam over the deck, tossed us about, and drenched us to the skin. I clambered back out of the hold around midnight, blanket-wrapped against the damp, chill, and mosquitoes, stinking of wet woolen breeches, doublet, and sodden shoes. It was a total immersion experience. I sat in the stern taking some tobacco, reflecting on the adventure. Reenactors live for this stuff—time-travel days.

The Dove moored at the Washington police docks behind a chain link security fence, lighted all night by halogen floods. We gave tours of the ship and weapons demonstrations to school groups during the day, and ventured onto the streets of the nation’s capital to pub-crawl, still wearing our fetid 1600s ensembles, swords, cutlasses, and all. Those were different days in the District of Columbia.

Around the world, most of us have seen reenactors—as extras in such motion pictures as Gettysburg, Glory, and The Patriot, and in television miniseries like The American Revolution, if not in person.

These days there are Woodstock-scale set-piece reenactments such as commemorative battles organized and sponsored by buffs, preservationists, and promoters, which can draw more combatants than the original engagement. The American Civil War has the largest reenactor following, with more than 40,000 adherents in the United States, and more overseas. More state fair–scale remembrances occur annually from coast to coast, such as the World War II Weekend each June at the Mid-Atlantic Air Museum in Reading, Pennsylvania.

There are participants-only immersion events, like private forays into the wilderness, for a handful of enthusiasts carrying thousands of dollars’ worth of museum-quality reproduction gear, weapons, authentic foodstuffs, and hand-stitched clothing. There is nothing modern that would be out of place in the past, and outsiders never witness the bivouacs.

Time-line events present multiple eras at once, such as Military through the Ages convened every March at Jamestown Settlement. They are not reenactments per se, but gatherings of reenactors time-tripping on wars ranging from remote antiquity up through today’s.

The common denominator is the concept of “living history.” Coined by historian Carl Becker in 1931, the term has been adopted, and adapted, by museums, historic sites, and event planners, and especially by individuals—buffs in autonomous groups of a handful to 100 or more, trying to create an authentic representation of the past to share as comrades. Becker said:

The history that does work in the world, the history that influences the course of history, is living history, that pattern of remembered events, whether true or false, that enlarges and enriches the collective specious present. For history to be of value, it must reach the people and move them both emotionally and intellectually.

Reenactors live history as experiential, individualistic, sensory, and immersive moments—why just read about the past when you can dress, eat, sleep, and smell like it? Above all is the desire is to personally connect with an authentic past and roll around in it.

Highbrow reenactors prefer to call it experimental archaeology or living history, putting old things and old life skills to a function test, or verifying their readings of the record. To one demographic of Americans it’s about blood ties, too, retracing their forebears’ footprints, experiencing things, places, and events belonging to their families. For other demographics, it’s little more than history-themed role-playing and escapist fantasy.

When did it start? Why do they do what they do? Who are these folks? Let’s see.

Gladiators dressed as heroes of ages past, and staged grand battles in Roman amphitheaters. There were tournaments with ancient Roman themes in the Middle Ages. Victorians re-created medieval jousts, and battle re-creations have long been part of military training.

In 1822, veterans of the American War for Independence reenacted the 1775 Battle of Lexington. In 1902, Crow Indians and militiamen reenacted Custer’s Last Stand near Sheridan, Wyoming. But none of these commemorative pantomimes was quite as moving on the scale emotionally and intellectually, as Becker said, as what emerged in the United States after World War II and spread round the globe.

Mainstream military reenacting is an artifact of the twentieth century. Since the 1930s, perhaps earlier, there was competitive target shooting among antique long-rifle aficionados. At first, they fired antique weapons; then exactingly crafted replicas. This, the black powder, muzzle-loading rifle movement, was momentarily interrupted by World War II. After VJ Day, it bounced back, grew rapidly, and spread from coast to coast.

In 1949 and 1950, a group of enthusiasts in the Washington, DC, area, led by Ernest W. Peterkin and John Rawls, established the North South Skirmish Association, which organization has conducted shooting matches at its home range in Winchester, Virginia, ever since.

Soon military drill was added for realism—loading and firing weapons in teams as soldiers did in battle, according to Civil War era drill manuals. This was followed by attempts at loosely simulating uniforms—blue for the Yankee teams and grey for the Confederate platoons was close enough. Muskets and canon were fired with live ammunition pointed at targets, not loaded with blanks, or pointed at each other.

Observance of the centennial of the American Civil War from 1961 to 1965 was really the first ragged volley fired in the reenactment hobby. The black powder shooting fraternity wanted in, of course, but their focus had been on target shooting, less so on wearing authentic uniforms or trying to experience firsthand the hardscrabble life of Civil War soldiers. Enter the next generation of buffs—the Baby Boomers coming of age. What emerged was a melding, leveling experience that characterizes the first generation of the hobby.

In 1966 a group of University of California at Berkeley students of medieval history and science-fiction and fantasy fans got together and formed the Society for Creative Anachronisms, “as a protest against the twentieth century,” their website says. Today, medievalist reenactors of the SCA, as they are known, claim 60,000 participants worldwide, focusing their time-tripping on the eras before gunpowder.

The next national good excuse to reenact—the Bicentennial of the American War for Independence—ran from 1975 to 1983. It provided fresh opportunity and brought together in one shared and transforming experience two antagonist generations, the youthful and long-haired don’t-trust-anyone-over-thirty gang and their fathers’ clean-cut crowd, during a polarized era in American history.

Middle-aged executives and veteran military officers fell in under the command of twenty-something art school dropouts and assorted history hippies on alternative career paths. Escapees liberated from their twentieth-century status, politics, ranks, and roles, they tried to create a shared patriotic experience. In his 1984 book Time Machines: The World of Living History, anthropologist J. Anderson called it a “secular mystical experience.”

But that was then. The first generation of reenactors has largely retired or died. A new generation has succumbed to the allure of the past, and the Internet and social networking websites have replaced the typewritten, photocopied regimental newsletters of the twentieth-century reenactor organizations.

Cyberspace has created keyboard commandos who, with Internet courage, take to the field online more than they assemble, drill, shoot, or make the uniforms and equipment, or venture into the great outdoors together. Rather than forming a local group to re-create a particular regiment from a particular war in particular detail, today’s reenactors tend to be geographically scattered. Meeting occasionally, if ever, they jump from one uniform to another, one war to the next, sometimes wearing a uniform once before it’s added to the collection in their closet. They still are drawn by history, however.

British novelist L. P. Hartley wrote that “the past is a foreign country, they do things differently there,” and who wouldn’t like to go exploring foreign countries?

Tens of thousands of hobbyists to the contrary, we hear gloomy reports of how little Americans know of their history, how poorly they score on tests, how desperate the situation is, and how irrelevant most feel history is.

Something’s amiss.

The number one pastimes of Americans include genealogy, authentically restoring and furnishing old houses, collecting antiques, history-themed war-gaming, and tuning into the steady stream of history programming on cable television. To say Americans dislike history seems overstated.

Living-history pursuits are “very Presbyterian,” according to anthropologist Anderson; they lie “outside the boundary of established academic and public history” and thrive “on independence.” He writes, “Each . . . unit makes its own covenant with historical truth and determines the way it will carry on its dialogue with the past.”

So, if the present is seen as specious, and sometimes history seems to be strangled until it confesses something, the reenactor looks for emancipation in escape to a fully faithful, if re-created, reality of living history.

Historian Howard Zinn wrote, “If you don’t have any history, it is as though you were born yesterday. If you were born yesterday, you will believe anything,” motivation enough it seems to drive armies of these independent weekend warriors and armchair historians deeper and deeper into their own dialogues with their past, and thank goodness.

D. A. Saguto is Colonial Williamsburg’s master boot and shoemaker, is editor and translator of The Art of the Shoemaker, and has a commission in the 71st Regiment (Fraser’s) Highlanders Veterans’ Company.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Tony Horwitz, Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War (New York, 1998).

- Jay Anderson, Time Machines: The World of Living History (Nashville, 1984).

- ———, The Living History Sourcebook. (Nashville, 1985).

- Patrick O’Donnell, The Knights Next Door: Everyday People Living Middle Ages Dreams (Bloomington, IN, 2004).

- Jenny Thompson, War Games: Inside the World of Twentieth-Century War Reenactors (Washington, DC, 2004).