Page content

Online Extras

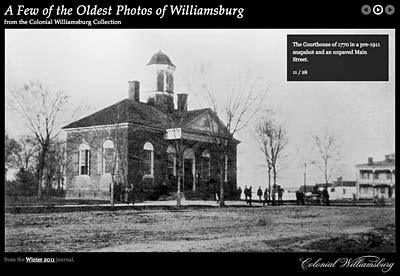

A Few of the Oldest Photos of Williamsburg Slideshow

A Few of the Oldest Photos of Williamsburg

Since at least 1702, when Switzerland’s Francis Louis Michel toured Williamsburg and sketched some of what he saw, illustrators and engravers, painters and draftsmen, artists and amateurs, have been executing images of the old Virginia capital and its denizens. But not until a photographer fetched up in the city, perhaps in the 1850s, could a picture capture the place and its people with the precision of light in a sliver of time.

What Williamsburg looked like before the thought of its restoration had crossed anyone’s mind, when the inheritance of the townsfolk was the eighteenth-century structures that sheltered their ancestors, is a matter of moment not only to their descendants or historians or architects or preservationists but to people simply intrigued by glimpses of the past, to a person who just wants to see it for himself.

Marianne Martin is mistress of a collection of such images from then, a special collection, pictures of the city’s yesteryears. Visual resources librarian at Colonial Williamsburg’s John D. Rockefeller Jr., Library, she and George Yetter, associate curator of architectural collections, preside over shelves and shelves of albums and boxes of snapshots, family photos, street scenes, black-and-white studies, for-the-record shots, and more that date to Williamsburg’s 1860s. Asked for a sampling of the oldest photos of the city, pictures that date to those days, Martin and Yetter gathered the copies that appear in these pages.

Yetter used some of the best of the collection, an assembly taken from albumen prints, daguerreotypes, glass plates, and the like, in his volume, Williamsburg, Before and After. But the library’s resources are so rich it takes more than a book to hold them. It takes rooms, rooms in which in the space of a tick of the clock visitors can lose themselves for hours among the men and women, the boys and girls, the houses and yards, the thoroughfares and footpaths trapped in the filament of a minute, stilled by the camera’s shutter, fixed in the silver shadows of what once was and otherwise is no more.

—Alexander Chesterfield