Page content

Historical Rivalry

Virginia's Jamestown was the continent's first permanent English settlement. So how is that Massachusetts's Plymouth has precedence in the minds of so many Americans?

By James Axtell

Jamestown and Plymouth vie for primacy in America's recollection of its history, Plymouth usually winning despite Jamestown's precedence. D. A. Saguto's Virginia soldier and Mike Durling's Massachusetts Pilgrim cold-shoulder each other.

The ruins of Jamestown's brick church and Plymouth Rock are rival icons of settlement. The rock's authenticity is suspect.

A re-creation of Jamestown's Fort trails a dismal, distant second to the Mayflower as symbol of America's founding.

Carmella Pocahontas Richardson, thirteen, portraying Pocahontas, and twenty-something Richard Peeling, as John Smith, are the same relative ages as their historical counterparts.

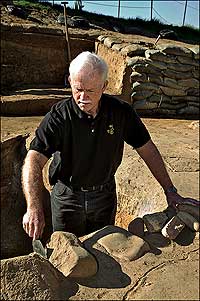

Bill Kelso headed the discovery of Jamestown fort, whose memory had washed into the James River—as, it was believed, had the fort—giving Plymouth an edge in the founding narrative.

Jamestown still yields discoveries, and modern archaeology has reconstructed much about the early days of English settlement, but it has not yet replaced Plymouth in the American imagination as birthplace of the nation.

Jamestown, personified by Saguto, above left, still argues the priority of its claim on English America's historiography against the misconception about the advent of Plymouth's Puritans, represented by Durling, as Jamestown's 400th anniversary nears.

As Jamestown approaches the May 2007 four-hundredth anniversary of its founding, officials in charge of the commemoration must be worrying about more than the narrow roads that lead to the historic island, construction deadlines, and projections of tourist turnout. They know the site of the first permanent settlement in English America also has an enduring image problem and a bit of an inferiority issue. Until the relatively recent rediscovery of the site of the original fort by Bill Kelso's intrepid band of archaeologists and its newsworthy finds, Jamestown has played second fiddle to the Plymouth Colony throughout the nation's postrevolutionary history.

Despite a thirteen-year age advantage, Jamestown has not secured the prime place in the American public's minds or hearts. School and college textbooks are not to blame: whatever else is wrong with them, their chronologies still assign precedence to 1607 Jamestown over 1620 Plymouth and the 1630 Massachusetts Bay Colony. Even the uneven quality of teaching and learning in our academies, as measured by standardized exit exams or jaw-dropping media polls, cannot explain why Jamestown is consistently rated the runner-up among early colonial icons. Something else is at work.

The question is twofold: Why does Plymouth command our national attention and affection? And why doesn't Jamestown?

Before we tackle those questions, we should recognize three other candidates for the "founding colony" prize, none of which ever wins enough primary votes to get on the ballot. The Spanish were in Florida early in the sixteenth century, first hoping to find more gold than Caribbean riverbeds and placer mines yielded and, when that proved elusive, to secure the Florida Strait for its returning treasure fleets from Central America and Havana. The murderous expulsion of an erstwhile colony of French Protestant "heretics" led to the founding of St. Augustine in 1565, which in turn gave Spain claim to at least chronological priority in the memory of all the Americas.

Another claimant is the short-lived English colony—or, more accurately, colonies—on Roanoke Island in the mid-1580s. Walter Ralegh's plan to plant a fortified privateering base just behind the Outer Banks was aimed at the Spanish flotas, which sailed on the Gulf Stream past Florida before heading home. Beset by poor planning, ferocious storms, and worse Indian relations, Roanoke can only make claim on the public memory for its unwelcome gift of "Virginia"—for the "Virgin Queen," Elizabeth I—to the proud colony of North Carolina and its mysterious but understandable disappearance. No one remembers the local Indian chiefs, in part because the leading one changed his name in medias res, the English military commander of the first colony, the largely absentee governor of the second, or the meaning of the letters "CRO" carved on the deserted fort.

Spain has another candidate, nearly as early as Jamestown, but because 1610s Santa Fe was founded in distant, dusty New Mexico, it has much less notice and only regional affection. The reason Hispanic places like St. Augustine and Santa Fe can't compete with the Anglo likes of Jamestown and Plymouth is that the Spanish carry some burden of the Black Legend, the largely Protestant and intensely English attribution of preternatural cruelty, greed, and bloodthirst to Europe's sixteenth-century heavyweight. Envying Spain's success in becoming rich and carving out a global empire, the English had to believe in their own religious purity and colonial altruism. When Great Britain and later the new United States were able to reduce Spain to impotence in eastern North America, nationalistic historians on the winning side, as is their wont, effectively wrote the losers out of the story, except as a moral foil.

Jamestown suffers from some of the bad press that Roanoke and the Spanish presidios get. Its goals were unworthy of the new nation's self-image, its early years were disastrous, its racial and ethnic record was shameful, and it barely survived into the eighteenth century.

As a creature of the Virginia Company of London, the joint-stock enterprise that sponsored the settlement, Jamestown was dominated by aggressive young men on the make. It attained none of its redeeming religious goals or moral schemes: profit for investors was its reason for being and martial law was often its mode of government. With an Anglican church and minister, it earned no historical credit as a refuge from religious persecution or bastion of tolerance. Gold lust and tobacco fever have never seemed worthy goads to colony or nation building, at least in retrospect.

Nor were the colony's early years filled with inspiring triumphs over adversity. Because it was built on a salty malarial swamp of an island, in the middle of one of the most powerful Indian confederacies in eastern America—the Powhatan—Jamestown lost more settlers than it sustained. Poor planning, inadequate supplies, and self-aggrandizing leaders caused widespread mortality during the infamous Starving Time. Ham-handed relations with chief Powhatan's bellicose tribes led to wholesale death, particularly during the equally infamous native uprising of 1622, in which a third of the colonists were killed. The royal takeover of the colony two years later certified the company's failure to cope with American challenges. Another surprise attack in 1644, which killed some five hundred Virginians, was more than enough to destroy the illusion of repaired Anglo-Indian relations.

Long before Time-Warner film The New World, Jamestown provided the public with one icon of benign race relations. Americans feeling guilty about the nation's treatment of its native peoples embraced a fanciful image of "princess" Pocahontas's romance with Captain John Smith, her willing conversion to Christianity, and her happy marriage to tobacco planter and widower John Rolfe. It mattered not that a bachelor-soldier in his thirties like Smith was an unlikely love interest for an Indian girl not yet in her teens, that she was kidnapped by the English and forcibly converted by an Anglican minister to whose house she was committed, and that her much older farmer-husband said he married her not for "carnall affection" but for the good of the plantation, England's honor, his own salvation, and the conversion of "an unbeleeving creature" to the true faith.

Jamestown has a better claim to iconic status on political grounds. In 1619, Virginia established an elected House of Burgesses to balance the near-dictatorial power of the governor and his council. This timid move toward representative democracy—only white, male heads of property-owning households could vote or hold office—might have been more memorable had the assembly not first met in a daub-and-wattle church long since vanished, making pilgrimages less feasible.

Equally inconvenient is the colony's long and sordid history of black slavery, also begun in 1619 when a Dutch ship sold some of its African cargo as servants to labor-starved planters unable to obtain willing workers from the pugnacious Powhatans. When the town burned for the third time in 1693 and the colonial capital moved to Williamsburg six years later, visitors were left with one less reason to put the original settlement on their vacation itineraries.

When the National Park Service declared Jamestown a historic site in 1930, conducted archaeological excavations in 1934, and created a museum for the colony's 350th anniversary, the town consisted of remnants of house foundations and the tower ruins of the fourth—and first brick—church, burned during Bacon's Rebellion in 1676. Since it was believed—mistakenly—that the original fort site had eroded into the James River, the town's remains had the barest of interest for visitors; a newly built museum did little better.

To confound visitors more, and also in 1957, the state built an unfocused hodge-podge of a museum and replicas of the original fort and ships a short distance away on the mainland and called it Jamestown Festival Park—now Jamestown Settlement. This gave visitors a more accurate image of the founding English colony, but it was not on the original site and contained no authentic artifacts or monuments of iconic status.

Both sites, moreover, had to contend with the larger, more visitor-friendly, more patriotically oriented Rockefeller restoration of the colonial capital at Williamsburg, with its aesthetically pleasing Governor's Palace and historically charged Capitol not far from the College of William and Mary's restored Wren Building. Five miles from Jamestown, as the crow flies, the Revolution at Williamsburg trumped the founding in America's memory.

All of these circumstances allowed Plymouth to lay first claim on the public's attention, despite two minor similarities to its southern rivals. Like Roanoke, Plymouth might have been located in "Virginia." The Pilgrims had permission from the Virginia Company to settle within its chartered territory as far as 41 degrees north. They were headed for the mouth of the Hudson River when they tangled with the sandy shoals of Cape Cod and chose to head north to an hospitable beach and a well-watered, partially cleared site soon to be christened Plimoth.

Like Jamestown, the Plymoth colony lost half its population during its first year. Its settlers had arrived after a two-month voyage and weeks on the Cape in the teeth of a New England winter, without housing or adequate food and supplies. But unlike the Virginians, they never thought of leaving or made the attempt. They came and continued to come in families, headed by God-fearing patriarchs. And they were determined to raise their children in a purified Calvinist faith, separated from what they saw as England's social and ecclesiastical corruption and from the alien and worldly customs of the Dutch cities to which many of them had fled years before.

But Plymouth's other advantages were more numerous and lodged it indelibly in the new nation's mythic past. In addition to its religious mission and family orientation, Plymouth has at least half a dozen features that maintain its iconic lead over Jamestown. The first is the vessel of transfer. The Pilgrims came in the storied Mayflower, a single ship whose botanical name has graced a replica and is the instantly recognizable title of a current bestseller. The first Virginians made their passage in three unprepossessing craft, whose names are obscure even in Virginia households. When my teenage son worked as a Jamestown Settlement interpreter onboard the replica flagship Susan Constant, he was frequently asked whether the smaller Godspeed and Discovery were the Niña and the Pinta.

The Mayflower also lent its name to the compact that the passengers, lying off Cape Cod on November 11, 1620, drew up to govern themselves. Pledging "all due submission and obedience" to King James I, the forty-one adult male signers constituted themselves "a Civil Body Politic" for the making and execution of laws for "the general good of the Colony." In all regards but one, this was an unexceptional document. Puritan church covenants were similar, and the Virginia Company had voted shortly after the Pilgrims left to allow leaders of "Particular Plantations" with their "gravest" advisors to establish laws and order until "a form of Government" could be "settled for them" in London. But the Pilgrims exercised an unusual degree of what their leader William Bradford called "liberty" because they had slipped beyond Virginia's patent into New England, "which belonged to another government, with which the Virginia Company had nothing to do." Virginia's installation of an elected assembly the year before required no such derring-do.

When the Mayflower moved to Plymouth and some of its male passengers disembarked, they allegedly set foot on a two-hundred-ton boulder, set incongruously on the otherwise sand beach. There is no contemporary evidence for such an improbable landing—only the say-so of a ninety-five-year-old descendant of one of the founders—but the rocky advent has been immortalized in picture and verse ever since. As fixed as the rock is in America's iconology, it moved around as much as the Pilgrims themselves and wound up twenty times smaller than it began. Sliced like a bagel in 1774 for removal to Liberty Tree Square, the mobile top half accidentally split in two half a century later before the whole was mortared back together and enshrined in a variety of monumental cages on the waterfront. There it reigns today, greatly diminished by waves, weather, and the incessant demands of modern pilgrims for souvenirs and talismans of America's most famous arrival.

Compared with Jamestown's relations with its native neighbors, Plymouth's were a picnic. They did not begin that way on the Cape, where the hungry newcomers dug up Indian graves for keepsakes and caches of seed corn and helped themselves to choice items from abandoned wigwams. But they also carefully covered the graves and made restitution in trade goods as soon as they could. The presence of two English-speaking Indians, Samoset and Squanto, proved heaven-sent as the Saints navigated the tricky shoals of native politics and diplomacy. As every American schoolchild learns, Squanto also taught them how to plant Indian corn with fish fertilizer and other American secrets of survival.

The following autumn, at an unknown date, the Pilgrims invited the Wampanoag sachem Massasoit and some of his people to a traditional English harvest festival. Fortunately, the Indians contributed five deer to the three-day celebration; the hosts had not reckoned on feeding the ninety men the chief brought with him. This equally iconic celebration of the First Thanksgiving—despite Virginia's claim of priority at Berkeley Plantation in 1619—was given lasting authority by President Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War when he declared Thanksgiving a national holiday. Countless artists have done the rest.

If Plymouth's historical assets were not enough to put it permanently ahead of Jamestown, it also enjoyed superior publicity. From the Revolution to late in the nineteenth century, New England was the arbiter, standard, and primary source of American culture. Its poets, novelists, orators, historians, and textbook writers saw to it that Plymouth became and remained America's "first" and best-known colony. Plymouth's last two centennials especially were grand occasions for reconfirming its place in the nation's memory. And when the outdoor history museum Plimoth Plantation was mounted in 1947, a decade before the re-creation at Jamestown, the New Englanders' lead was nigh insurmountable.

It remains to be seen whether the archaeological discoveries at the original fort and the rebuilt ships, reconfigured fort, and enlarged museum at Jamestown during its fourth centennial will give upstart Plymouth a run for its money.

James Axtell is the College of William and Mary's William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Humanities, a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, an authority on the ethnohistory of colonial North America, and the author of such books as After Columbus, Natives and Newcomers: The Cultural Origins of North America, Beyond 1492, and The Invasion Within: The Contest of Cultures in Colonial North America. This is his first contribution to the journal.