Page content

Tailoring the Tenant House

by Robert Doares Jr

Photos by Dave Doody

Pity that the video crew from television’s Fear Factor missed the scene at Colonial Williamsburg’s Tenant House site one afternoon last summer. Guests and interpreters shrieked and scattered as Thomas Hansford, the tailor who lives there, scooped up, barehanded, a foot-long garter snake as it slithered along the rail fence next to the dwelling. He carried the reptile to a thicket nearby. “I only wish I had a large black snake for under the house,” Hansford said. “Good against mice, you know.”

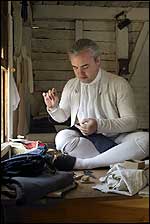

Portrayed by interpreter Mark Hutter, Hansford spoke with the verisimilitude that defines the Tenant House, the Historic Area’s only exhibition building free of concessions to modernity. No disguised plumbing. No electricity. No air conditioning. Just interpreters with a spontaneity born of the exigencies of life skills they practice as ordinary working people of 1774.

Interpreter Jay Templin, portraying carpenter John Drewry, is whittling a handle for a spade while an ashcake bakes on the hearth. “We do just about everything here except sleep,” he said. “We cut and split our wood, build fires, cook, eat, clean, do laundry and maintenance, haul water, build fences, and grow food, and practice our trades. It’s very much the daily rhythm for our sort of folk in the eighteenth century.”

Inside, Thomas Hansford and John Drewry—friends, fellow lodgers, tailor and carpenter—rest from the business of the day with seamstress and laundress Elizabeth Maloney, in persons of Mark Hutter, left, Jennifer Belvin, and Jay Templin.

Drewry and Hansford are boyhood friends and bachelor tradesmen who strike out on their own in colonial Williamsburg and save expenses by renting a home and shopping together. Tailor Hansford has hired a part-time laundress and seamstress, Elizabeth Maloney, played by character interpreter Jennifer Belvin. Though the three characters are based on real people of the eighteenth-century city, their configuration as associates on the site is a composited scenario.

Guests who happen upon the Tenant House sometimes wonder what the building is. The place’s rusticity leads first-time viewers to think it the home of a poor family. Some are surprised to learn that it would have been a rather good home for most Virginians of the middling sort, a modest structure with two rooms, window glass, wooden floor, brick foundation piers, and a brick chimney—a far cry from the tiny earthfast, or post-in-ground, abodes of the impoverished.

“The fact that the Tenant House represents the sort of home most of our guests would have occupied as colonial Virginians makes the place particularly valuable as a bridge to the past,” says managing interpreter Daniel Marshall, a supervisor of the site. “Saying to a family that this would have been their house helps put them in the right frame of mind for learning.

“People today can relate to the issues faced by the characters they meet at the Tenant House. Most people of the twenty-first century are not independently wealthy, and most have a mortgage or pay rent. We all have hopes of improving our lot, and we all have to make choices, just like folks back then.”

The Tenant House denotes the Historic Area’s shift toward presentation of a broader spectrum of eighteenth-century Williamsburgers. Its programming showcases the lives of working-class people, the greatest percentage of Williamsburg’s free white population. It also brings to the fore the subject of tenancy—the business of renting property—a facet of the capital’s history heretofore underrepresented. About half of the properties in eighteenth-century Williamsburg were rented or leased at one time or another, dividing the population into landlords and tenants—the term used for renters. Rental properties were called “tenements”—without later negative connotations of urban overcrowding. They ran the gamut from Custis Square, an elaborate gentry estate with one of Virginia’s finest gardens, to subdivided units in Dr. William Carter’s Brick House Tavern. Williamsburg landlords and landladies included gentlemen, merchants, planters, tradesmen, tavern keepers, and widowed householders. Tenants could be just about anyone with an income.

Landlord-tenant relationships had such familiar pitfalls as broken contracts, disagreements over maintenance, and the pressures of a tight housing market. Yet the business of renting property flourished. Emma Lou Powers of Colonial Williamsburg’s research department sparked interest in tenancy in Williamsburg and Yorktown with her 1990 paper on the subject. Former Historic Area program planners John Caramia and Christy Matthews saw a need to translate Powers’s research into programming for the presentation of a more realistic view of the economic diversity of the city’s residents. They spearheaded creation of a site to explore the world of working-class renters. The Tenant House opened in 1998.

The building had been constructed a few years before as a temporary winter shelter for interpreters at the rural trades site. It was slated for removal to make way for reconstruction of outbuildings at the Peyton Randolph House. Open ground on the northwest corner of Botetourt and Nicholson Streets, planted and farmed by the landscape department, seemed a likely plot for the orphaned house. Knowledge that two lost eighteenth-century buildings there had histories as rental properties of the Nelson family of Yorktown enhanced the plan. Not so fast.

The location, known as the Ravenscroft site and town lots 267 and 268 on the original plan of Williamsburg, contained archaeological remains of its two early edifices. They had been discovered through cross-trenching in 1954. Modern City of Williamsburg regulations preclude anything except placement of a temporary structure over original foundations in an incompletely excavated site. A compromise had to be crafted.

The city granted permission to move the house to the lots, for placement between the two original foundations, with the understanding that Colonial Williamsburg would first mitigate archaeological concerns. That was accomplished by a thorough excavation of a seven-by-ten-meter spot. Recovery of more than ten thousand artifacts showed heavy occupation in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and suggested full-scale excavation of the remaining terrain.

After the move, project planners turned to interpretive themes and staffing. As at other Historic Area venues, guests were to encounter “third-person” costumed interpreters, who contextualize from a present-day perspective, and character interpreters, also known as people of the past. Historical research produced a pool of real-life eighteenth-century renters. Since most of these tenants could not be linked to a precise location in town, a number of them could serve as fit subjects for portrayal at a fictive Tenant House.

One of sixteen tailors in Williamsburg in 1774, Hansford swapped needle for bayonet when he joined the army.

Successive casts of characters in each of the site’s first five years of operation embodied the precariousness of life for the lesser sort, townspeople whose fortunes might be on the rise or in decline. The stories told thus far include Mary Singleton and her daughter Rachel Whitaker, two widows in straitened circumstances; the Coopers, a free black family who themselves own a slave or two; and the family of James Atherton, a disabled carpenter and veteran of the French and Indian War. The annual turnover of characters invokes the reality that the average eighteenth-century tenant stayed in one location a year or so. There were, however, instances of long-term rentals. Cabinetmaker Peter Scott owned two tenements but lived and kept shop for forty-three years in a house near Bruton Parish Church that he rented from the Custis family.

Jay Templin, who played James Atherton, stayed on to portray John Drewry. Templin began his Colonial Williamsburg career in the carpenter’s yard before he took his first character role as a carpenter. The idea of pairing Templin and Hutter as cohabiting tradesmen was born of Hutter’s quest for a place to practice tailoring apart from other fashion trades interpreted in the Historic Area. For years, he interpreted London-trained tailor James Slate mostly at the Milliner’s Shop, side by side with tradeswomen. For his move to the Tenant House, Hutter studied Hansford, a Williamsburg tailor who ran away from his apprenticeship under Jonathan Prosser in 1771, struggled to make it on his own, and joined the Virginia army in 1775.

It was no stretch to place a tailor at the little tenement on Nicholson Street. Estate inventories document a variety of living and working conditions for Virginia tailors. A Virginia Gazette account of a lightning strike in 1766 describes a tailor’s home and shop much like the present Tenant House. Tailoring also fits with the interpretation of the hopes and aspirations of working-class people at the site. As the largest and most competitive group of tradesmen in any urban community—Williamsburg had sixteen shops in 1774—tailors exemplified economic mobility. A tradesman like Hansford began his career by serving members of his class, but in time might rise to serve his betters.

Such fortune smiled on Thomas Hornsby, presented as an archetypal Tenant House landlord. A tailor by training, Hornsby prospered as a merchant and as real estate investor. Though he never owned the Ravenscroft site, he accumulated perhaps the largest personal estate in town—royal governors excepted. At his death in 1772, Hornsby bequeathed Williamsburg rental properties to his nephews.

Maloney was a member of the largest group among colonial Williamsburg’s free whites, the working class.

These days, Tenant House guests may find a stocking-footed Hansford sitting cross-legged on his work board, stitching men’s suits or sewing in ladies’ stays by the light from his shop window. He will likely be in the company of his housemate, Drewry, or his laundress, Maloney.

Maloney adds perspective with her remarks on the good fortune the tailor and the carpenter had when they secured the rental of such a property. Its two-room construction and amenities—including a tea board and stand, and a looking glass—contrast with the barrenness of the one room with a dirt floor Maloney reports she occupies with her children a two-mile walk from town.

Once guests get beyond their astonishment that the Tenant House represents an urban and not a rural site, interpreters find it easy to engage them on just about any aspect of life, from trade and commerce, to the consumer revolution, to the influence of church, government, and other institutions. The variety of activities on site fosters flexibility in the presentation of the Historic Area’s thematic storylines.

Despite its effectiveness as an interpretive site, the Tenant House is a temporary amalgamation. What about the future?

Hutter has hopes for a permanent tailor shop, perhaps on Slate’s excavated yet unrestored house site on Duke of Gloucester Street. Others imagine the removal of the Tenant House for further study of the two original buildings, a prospect complicated by the protrusion of one foundation into present-day Botetourt Street.

Meanwhile, the Tenant House presentation has imparted to its participants a zeal for expanding the interpretation of colonial tenancy. Project coordinators envision pursuit of the topic at other documented eighteenth-century tenements about town, with renters and landlords of different social strata from those presented now.

You know, George Washington was a Williamsburg landlord, too.

Robert Doares’s story “But for the Saviour, I Could Not Bear It: The Story of Selim the Algerine” appeared in the summer 2002 issue of the journal. Doares is an instructor in Colonial Williamsburg’s department of Historic Area training.