Page content

Online Extras

Colonial Williamsburg Restoration Slideshow

Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library

Black-occupied homes in what became Merchants Square were among the buildings moved or torn down during the Restoration.

Barbara Lombardi

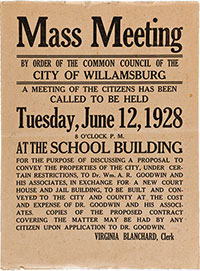

Notice of the meeting W. A. R. Goodwin called for a vote on the transfer of Williamsburg properties.

Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library

The Restoration purchased and tore down this recently built school on Palace Green, building a new one a block away.

Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library

The blacks-only James City County Training School, torn down and replaced on a different site by Bruton Heights School.

Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library

“White City” buildings demolished during the 1960s

Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library

African Americans students from Williamsburg and two counties moved into segregated Bruton Heights School.

Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library

The Restoration offered jobs for blacks, mostly service and clerical but also in the Historic Area.

Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library

Pay was low, but the work kept unemployment down during the Depression.

Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library

Chef Mack Williams, among the earliest blacks in Restoration management

African Americans and the Restoration of Williamsburg

by Mary Miley Theobald

The leading local promoter of the restoration of Williams-burg to its eighteenth-century aspect, the Reverend Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin, summoned townspeople to a meeting June 12, 1928, to put his plan to a vote. A College of William and Mary fund-raiser and professor, as well as rector of Bruton Parish Church, he had negotiated the details with the city and county governments. They had surveyed public properties, drafted contracts, and secured the assent of Goodwin’s once-anonymous backer.

The philanthropist, his identity no longer much of a mystery to people paying attention, had secured scores of private lots and buildings. It was as close to done as a deal could be, and its backers aimed to seal it this night with the agreement of the citizens at large. In the standing-room-only auditorium of the city’s new high school, Goodwin announced the town would become a national shrine. He reassured his mostly male audience it would profit “in spiritual, as well as material, ways. Every businessman will be benefited.” And, he said, they had Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller Jr. of New York to thank.

The ballots tallied one hundred-fifty to four in favor, but not everyone with an interest in the outcome got to cast one, as pro forma as these may have been. In those years, seven hundred of the town’s 2,500 residents were African Americans. None attended the gathering. In Jim Crow’s Virginia, they could not enter the whites-only school. Williamsburg’s black citizens heard secondhand the official word that the town would become a museum, and that white Williamsburg had voted its approval. The times being what they were, the city’s African Americans had no seats at the meeting.

The Restoration, as at first the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation was known, soon modernized the town with up-to-date water, sewer, electricity, paved roads, and a state-of-the-art fire station; it brought new school buildings, hundreds of jobs, and opportunity. Goodwin was right—everyone benefited. Nevertheless, Colonial Williamsburg’s creation displaced historic district enterprises and households, white and black, in the path of demolitions, reconstructions, and restorations. The adjustments were harder on the city’s African Americans than on its whites.

Before the Restoration, the city was an integrated mixture of black- and white-owned homes and businesses, although “people knew where the boundaries were,” says foundation historian Linda Rowe. Her research showed “eleven black households living side-by-side with eighty-six white households on the main street, Market Square, Palace Green, and the Capitol grounds. Five black families and thirty-three white households were neighbors on Francis Street. African American and white families lived on Prince George, Henry, Nassau, and York Streets.”

Black-owned businesses—including Banks Café, Crump Restaurant, Crutchfield Barber Shop and Tea House, Skinner’s Tavern, Hitchen’s Store, Smith’s butcher shop, and Theodore Harris’s vaudeville theater—spread about town as well. Goodwin, his words reflecting the attitudes of his times, said in a 1934 speech, “Up nearer the College was a row of tumbled-down modern stores and disreputable houses of some very reputable negroes. They had inherited the houses, as negroes often do, when no white man was left who would live in them.”

“In other places old homes of colonial days hung over caved-in foundations being held up by their rotten framing timbers. In one instance, the negroes who slept in one of these colonial buildings slept in rainy weather with umbrellas over them. They slept there without paying rent. Some sense of humanity was left, for who would seek to collect rent from dwellers in a colonial house whose only protection from the rain was an antique umbrella which leaked also?”

To remove most nineteenth- and all early twentieth-century structures from the center of the city, Rockefeller’s new Williamsburg Holding Company purchased more property and relocated owners. Vernon Geddy, an attorney who handled most of the Restoration’s real estate title transactions and became a Colonial Williamsburg vice president, said in a 1952 interview that he “always had splendid cooperation from most of the people of Williamsburg.” Whites who owned eighteenth-century houses that could be renovated for the Restoration usually had the option of surrendering their titles and moving back in after repairs to live rent-free as life tenants. There was as well, at least for College of William and Mary professors, the option of moving to such new white neighborhoods as Chandler Court next to the college.

Some of the city’s less-advantaged owners of 1700s homes had properties deemed poor candidates for life tenancy agreements, too time-worn for revitalization. Goodwin said, “This is not either a complete or in any sense an adequate description of Williamsburg as it was. Some few colonial houses retained a fair measure of their ancient grace and beauty, but not one of them was protected from fire and very few from the fire menace of neighboring fire-traps. The extent to which this was true may be realized when it is recalled that 442 buildings of modern construction have been demolished.”

Real estate agent Gardiner Brooks, who worked with Goodwin, too, said in a 1930 interview that he was having trouble getting African Americans to sell. They were “suspicious of the purchasing power of the white man’s money,” he said, and once a black man owned a piece of property, it was “hard to get him to turn it loose.”

At least thirty-six black families removed to neighborhoods outside the museum area with less or none of the assistance white families got. Two were offered life tenancies. Goodwin said he thought most would move away and “take care of the housing problem.” He was right. Some found homes in a new black neighborhood called Braxton Court, a few blocks west of the restored area. Others moved south of Francis Street on Henry Street, or north of Duke of Gloucester along Botetourt. The relocation of displaced residents, black and white, Rowe wrote, “established racially segregated residential areas along lines unknown in pre-Restoration days.”

Available to displaced black residents were six blocks along Botetourt Street where it intersects Franklin and Nicholson Streets. This was the site of the city’s black school, Union Baptist Church, Samaritan Odd Fellows Hall, and black-owned businesses and homes. The Restoration built a row of cottages for its African American workers. Painted white, the houses got the moniker White City. The section grew in the 1930s as African Americans were moved off the main street; it contracted in the 1950s and 1960s as Colonial Williamsburg raised support facilities and employee dormitories in those blocks.

Retired employee Edith Heard was born in a White City house and has happy memories of growing up in that neighborhood. Her father, a foundation chauffeur and mailman, rented a White City house for years. She remembers the brickyard across the street, where black men made most of the bricks used to reconstruct foundations and houses. Williamsburg’s restoration, she said, “was the best thing that happened to everybody, black and white. Many black people sold their property for big money and then bought more. The goal in those days was to build a brick house. Everybody wanted a brick house and their own property. Ninety percent sold their lot and bought acres of property and built a brick house. They upgraded. One family ended up with forty acres out of town. People prospered.”

The Williamsburg Holding Company bought white-owned Duke of Gloucester businesses and moved them to Merchants Square, the new shopping center it built in front of the college’s Wren Building. Black-owned businesses relocated outside the historic restoration boundaries. A few went to the triangle between Prince George, Scotland, and Boundary Streets. Others, such as Banks Café, the Crump Hotel, Epps’s barber shop, and a pool hall, moved to the Botetourt neighborhood.

Williamsburg churches built after the eighteenth-century—which is to say, all but Bruton Parish Episcopal—were torn down and replaced with new buildings outside the historic district. The original Mt. Ararat Church, an African American place of worship on Francis Street, was declared a firetrap in 1933 and demolished. A new Mt. Ararat was constructed across from the White City houses and diagonally across from the Union Baptist Church at Botetourt and Franklin.

The James City County Training School, a one-story, six-classroom school for African American children, grades one through eleven, was the Botetourt Street neighborhood landmark. Constructed in 1924, it consolidated children from smaller schools. Its principal lived steps away. It stood in the way of the Restoration, but was replaced with a modern and model, if still segregated, school just north of the Historic Area.

Restoring and reconstructing a colonial capital was an undertaking that brought hundreds of jobs to a town where the largest employers had been the College of William and Mary and Eastern State Hospital for the mentally ill. In the first seven years, Colonial Williamsburg removed 450 buildings and constructed 150 more, generating work for laborers, builders, and truck drivers. As tourists poured in, hotels, restaurants, and gas stations sprang up to serve them, creating more jobs. When the Great Depression of the 1930s paralyzed America, the Restoration chugged on. The national unemployment rate reached 25 percent; Williamsburg’s never exceeded 4 percent.

But “the pay was too low, and advancement was nil,” said Williamsburg-born Robert A. “Bobby” Braxton, who became the town’s second black city councilman. With exceptions, opportunities for African Americans at Colonial Williamsburg were low-wage positions in restaurants, hotels, laundry, and landscaping. This also was true at the college and the hospital and typical of the era. “You can’t look at history with twenty-first-century vision,” Heard said. “CW met integration ahead of the game, putting blacks in key positions.”

Until the 1930s, black women who worked for wages were employed mostly as domestics in white homes. The Restoration brought the prospect of a steady paycheck and higher pay, even if the majority of jobs on offer were the traditional positions of maid, laundress, or cook. Black women now left their domestic jobs in a rush, confirming a Goodwin prediction that the Restoration would make it impossible for white families to hire female servants.

Black men who had been farmers or had made do with seasonal or part-time work found full-time opportunities and an improved standard of living. In the beginning, most worked as chauffeurs, waiters, janitors, gardeners, cooks, grooms, and carriage drivers, but not all. Heard said Chef Crawford and Mack Williams were management from 1938, “brought to Williamsburg by Mr. John D. Rockefeller.” Executive Chef Ira Bonner and Earnest Heard “opened the Motor House Cafeteria” in 1957.By the 1960s, departments once closed to blacks were opening up, and opportunities to advance increased. In 1967 Edith Heard became a supervisor in the accounting office.

The restoration of Williamsburg brought improvement to African American schools. Early in the twentieth century, a young John D. Rockefeller Jr. had taken trips through the South to observe the sad state of African American education, a subject that had long concerned his family. He found not a single public high school for blacks in the South. Two crippling factors—racism and a low tax base—made improvement unlikely.

So Rockefeller launched a charitable foundation in 1903 called the General Education Board to support black schools and universities throughout the South. By 1905, his father had funded it with $42 million, slightly more than $1 billion in today’s dollars, a sum that tripled over the next couple of decades.

It was this mission that brought Rockefeller, who was by then fifty-two, to Virginia in 1926. On a visit to Hampton Institute—now Hampton University—thirty miles southeast of Williamsburg, he took a side trip to Williamsburg, where Goodwin had offered to show him the town’s colonial survivals. Because that visit led to the town’s restoration, it is no exaggeration to say that Colonial Williamsburg owes its existence to the Rockefeller family’s commitment to black education. That commitment directly benefited Williamsburg’s black community.

Williamsburg’s first postcolonial black school had opened in a rented room six years after the Civil War. A second opened thirteen years later in a two-room frame building behind today’s Market Square Tavern. It moved in 1908 to the Samaritan Odd Fellows Hall, a fraternal care-and-support organization at Nicholson and Botetourt Streets. During these years, there were about 130 black students in all grades taught by ten black teachers. The white schools had similar numbers but better facilities, and white teachers earned twice as much.

When the James City County Training School was built, it consolidated these small black schools into one location at Botetourt and Nicholson, across from the Odd Fellows Hall. By the late 1930s, the Training School had fallen into disrepair, and Colonial Williamsburg officials were eyeing that part of town for expansion. They proposed buying the Training School from the Williamsburg School Board, tearing it down, and building a school on thirty acres donated by Rockefeller, just north of the railroad tracks. The projected cost of the facility was $245,000, a sum far beyond what the local school board could afford.

It would be “the most up-to-date program for negro education in this country,” wrote Colonial Williamsburg President Kenneth Chorley in 1938 to Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes. Chorley asked for a federal grant. The school should have “the possibility of influencing negro education throughout the South,” he said, and be “much more important than simply another negro school.” Ickes approved a $95,000 gift. Rockefeller’s wife, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, contributed $50,000, and the facility, Bruton Heights School, opened in the fall of 1940.

“The James City County Training School was a nice building,” said Braxton, a 1956 Bruton Heights graduate, “but Bruton Heights was nicer. Fifteen schools closed when Bruton Heights opened—mostly one-room schools in York County and James City County,” whose students could now be bused into the new one.

Historian Andrea Foster wrote in her 1993 Ph.D. dissertation that Bruton Heights focused on job training, stressing such home economics courses as cooking and laundry that would equip students for jobs in Williamsburg’s hotels and restaurants. But by the time Heard graduated in 1961, its academic courses were college prep quality, thanks to the insistence of its principal and faculty. Bruton Heights, she said, offered technical courses, too. “You could choose domestic classes—cooking, sewing, and such—or not.”

From the day it opened, Bruton Heights was far more than a school. “It was a community center, too,” Braxton said, with amenities the black population had heretofore gone without, including an auditorium that doubled as the community movie theater, a gymnasium, a library, a dentist’s office, and a clinic. During World War II, it served as the black USO for the Peninsula.

The old James City County Training School was demolished. An eighteenth-century building, the Davenport House, had once stood on the site, and many wanted it reconstructed. “Fortunately the school had very shallow foundation walls,” Colonial Williamsburg archaeologist Meredith Poole said, so the underlying Davenport House remains were minimally impacted. The site was excavated in 1954. Another colonial building, the Ravenscroft House, once stood opposite the Training School. That site, too, was excavated in 1954, and in 1997, and again from 2006 to 2008. Colonial Williamsburg officials of the 1950s entertained hopes of reconstructing those two houses and enlarging the Historic Area. “The block was actually a very important element in the colonial landscape,” Poole said. The school site has seen subsequent use as an exhibition brickyard, a carpenter’s yard, and since 1997, a pasture.

With its academic anchor gone, the black community around Botetourt Street shrank as Colonial Williamsburg gradually bought up land and used it for support and maintenance facilities. In 1949, the foundation purchased the Crump Hotel and demolished it a year or two later. The Union Baptist Church was torn down in the early 1960s after its congregation moved to Highland Park, a black residential area north of today’s Governor’s Inn. During those years, two of the White City houses were moved to Highland Park. The rest were torn down. Today one building remains in the old neighborhood, the Mt. Ararat Baptist Church, an island in a sea of parking lots, office buildings, maintenance shops, and warehouses.

By some lights, the Restoration was a mixed blessing for Williamsburg’s African American community. While some blacks saw increased segregation and low-wage jobs, others saw job opportunities and improved schools. During subsequent decades, “senior administrators changed the environment,” said Rex Ellis, Colonial Williamsburg’s first African American vice president.

During the turbulent years of desegregation, such foundation executives as John W. Harbour, vice president and Williamsburg school board chairman, were “at the forefront to do everything possible to make sure the community transitioned in ways that did not create unrest. The theater was integrated when some blacks simply went in and sat down. School integration occurred with little conflict, no marches, riots, or violence. In that respect, CW was more of a pacesetter than most institutions and a much better organization than it had been in the early years.

“When you see the third generation of families working for the foundation, when you see retirees living in the area defending the organization, when you see the professional way the foundation acknowledged Bruton Heights as an African American school—these are all signs of a solid, credible, and nurturing relationship” that exists today between Colonial Williamsburg and Williamsburg’s black community.