Page content

Internet Archive

Benson Lossing commissioned this 1850 sketch of the Magazine, ground zero of the Revolution in Virginia, by a college student.

Internet Archive

The 1716 Magazine, overlooking Market Square, remained in good repair when it appeared in an 1845 pictorial history of Virginia.

Colonial Williamsburg

Its military usefulness over with the end of Civil War, the Magazine about 1881.

Colonial Williamsburg

In this antebellum drawing, the Magazine had lost its surrounding wall, and a market lean-to had been added to its south side.

Colonial Williamsburg

In 1890, the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquity purchased the building, minus a wall that collapsed in 1888, to forestall its ruin.

Colonial Williamsburg

A horse grazing nearby and Bruton Parish Church’s tower in the background, the repaired Magazine early in the twentieth century.

Special Collections, Swem Library, William and Mary

Checkerboard bricks gathered from old foundations repaired the Magazine about 1906.

Colonial Williamsburg

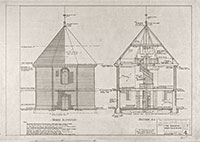

1935 architectural restoration drawings done by Colonial Williamsburg draftsmen.

The Magazine

Photo Essay

by Alexander Chesterfield

Nearly sixty-year-old, eight-sided, brick fasthold of arms, ammunition, and explosives in Williamsburg’s central square became the flash point of the Revolution in Virginia. Beyond the boundaries of the Old Dominion, the three-story curiosity’s place in the march to American independence is, perhaps, not as well known as that of Lexington’s green or Concord’s bridge, but it was as important.

Let’s begin at the beginning.

Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood proposed the storehouse in 1714 to safeguard weapons and gunpowder he had secured from Queen Anne for Virginia’s defense—muskets and munitions that he said lay in an older depot exposed to neglect and embezzlement. Spotswood offered to loan funds of his own for the new building, may have designed it, and quickly obtained the General Assembly’s assent. About £200 and two years later, contractor John Tyler turned over the keys to the bastion that the legislature had decreed “be called the magazine.” Before Colonial Williamsburg began to renovate the depot and restored it to its rightful title in 1933, the Magazine had been identified, too, as the as the Public Magazine, the Powder Magazine, and, lately, the Powder Horn. Often the adjective “old” preceded the labels.

Appellations aside, since Friday, April 21, 1775, it has been known best as the place to which James Murray, Earl of Dunmore and the colony’s last royal governor, touched the spark to a train of events that fired Virginia’s enthusiasm for independence from Great Britain, and led to a unanimous declaration of the thirteen united states assembled in Philadelphia.

Executing orders from London, his lordship Earl of Dunmore summoned to Williamsburg a royal marine and twenty armed sailors from the schooner Magdalene, anchored in the James. Between 3 A.M. and 4 A.M., he dispatched them with a small Governor’s Palace wagon to the Magazine, where they spirited away fifteen of the seventeen or so half-barrels of government gunpowder on hand before the raiders were discovered and the alarm sounded.

Bands of Virginians flew to arms, suggesting that the theft had left the province not so defenseless as was alleged. In any event, careful and cautious men forestalled violent reprisals, but fearing for his and his family’s safety, Dunmore abandoned this the colony’s capital and his post June 9. Virginia quit its allegiance to England on May 16, 1776, becoming the first of Great Britain’s possessions to break with the mother country, and instructed its delegation to the Second Continental Congress to move the same for the other twelve. The motion carried. Thomas Jefferson wrote up the result.

The Magazine’s years of military service had been enhanced by construction of a guardhouse and ten-foot-tall wall in 1755, and a fortification trench circa 1776. The thirty-three-foot, five-inch wide, sixty-foot-tall octagon was a repository of such martial items as axes, basins, bayonets, bedclothes, belts, blunderbusses, buckshot, canteens, cannon, cannonballs, carbines, cartouche boxes, clothes, cutlasses, drums, Dutch ovens, flints, hand grenades, hatchets, hats, holsters, kettles, knapsacks, lead, mallets, match rope, mortars, muskets, picks, pistols, powder horns, rifles, sheets, shoes, shovels, shot, shot bags, swords, tents, tent poles, and trade guns.

Virginia’s government and its gear moved to Richmond in 1780, leaving the Magazine to local troops, who found less and less use for it. By 1797 the structure served Williamsburg for a market house. The second floor became a Baptist meeting house in the 1850s. The first floor was still a venue for kitchen provisions in 1857, seven or eight years after visiting historian Benson J. Lossing had the building sketched for his two-volume The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution or Illustrations, by Pen and Pencil, or the History, Biography, Scenery, Relics, and Traditions of the War for Independence, and reported it was a partial ruin. Before the Civil War, when the Confederates made it an arsenal, the Magazine housed a dancing school, and after the fighting, turned into a livery stable.

It was still sheltering horses and hay when one morning in 1888 someone noticed the northeast wall had fallen. The Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities—as Preservation Virginia was then called—paid Moses R. Harrell $400 for the deed in 1890, rebuilt the east, north, and northwest walls, as well as the one missing, with bricks scavenged from area wrecks, and turned the Magazine into a cabinet of historical knickknacks and miscellany.

Colonial Williamsburg, partnering with Preservation Virginia, by 1935 had spent $11,811.28 on another restoration of the building, and $8,865.16 to rebuild the wall, acquired a lease on the property in 1946, restored the building again in 1952, and took title thirty-four years later. It stands today—supported by the John and Linda Muckel Endowment Fund for the Magazine—appearing much as it did in 1716, as an exhibition building stocked with eighteenth-century arms. But no gunpowder.